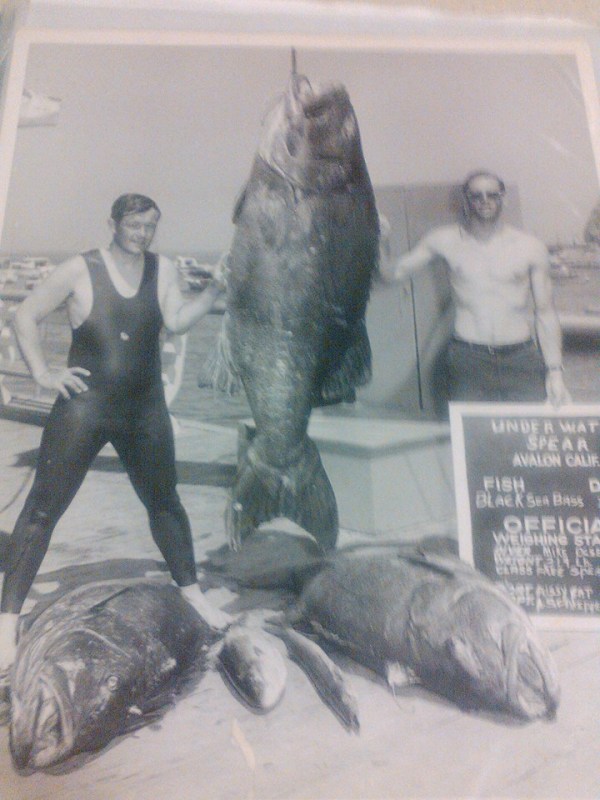

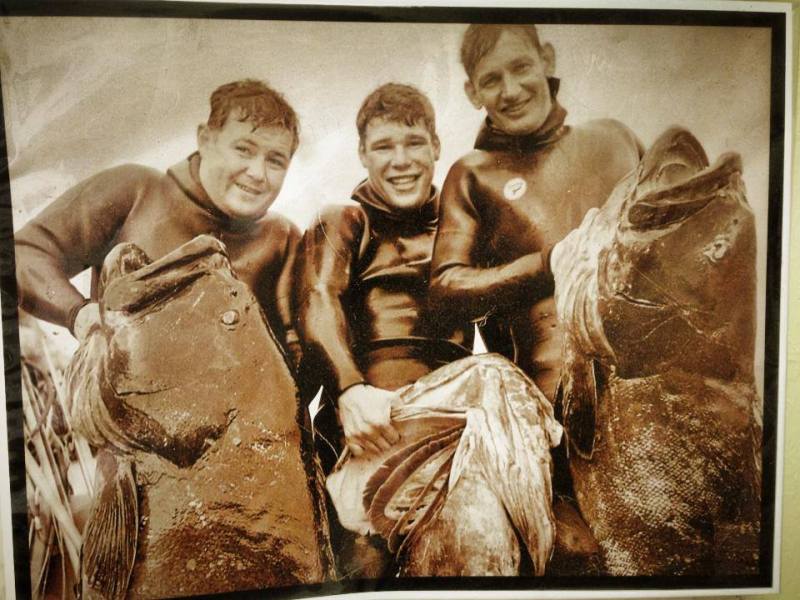

Al Schneppershoff was one of the most respected blue-water spearfishermen, freedivers and all around watermen in the world. He, and the men who came in the few decades before him, are considered the founding father of the sport in American waters.

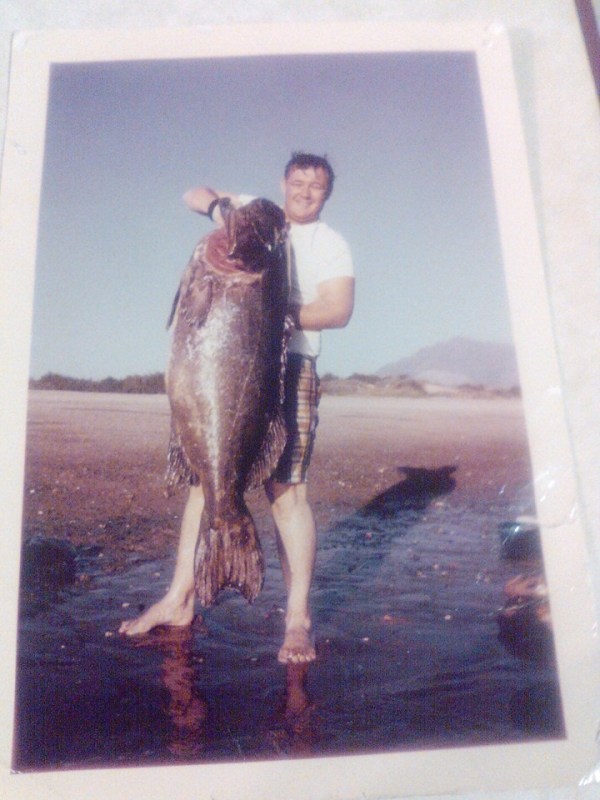

In the 1960s and 70s Al, a big man with an uncanny stamina for diving and stalking fish, was at the top of his game. He was the LeBron James of the sport. An MVP, always first in the water and last to leave…and he always got the prize … the biggest fish. He swept competitions like polished tile floors and pulled up game that made Loch Ness sound a little more plausible.

Every article I’ve read about Al mentions his good nature, his contagious belly laugh, his generous personality and of course his connection to the ocean and its inhabitants. Al loved to make people happy, and he wanted nothing more than to share his passion for salty water and hunting fish. But this story isn’t entirely about Al Schneppershoff Sr., it’s about his son, Al Schneppershoff Jr. … an equally talented waterman who learned to dive before he learned to ride a bike, followed in this father’s watery footsteps, became a respected spearfishing guide and ocean enthusiast.

What makes this story particularly fascinating is the human capacity to overcome loss and find passion, redemption, and joy in place of fear, anger, and pity.

“MAN ATTACKED AND KILLED BY GREAT WHITE SHARK,” was the Los Angeles Times headline in September of 1973.

On September 9, 1973, Al Schneppershoff, 37 at the time, was spearfishing for tuna off Mexico’s Guadalupe Island. It was late afternoon, and Al was alone in the deep blue as his son watched from the boat. The waters around Guadalupe Island are 200 feet deep and full of life. They attract predators of many kinds, not just the two-legged, breath-holding men who have to don wetsuits to share the space with the more adept and native ones. Just below the surface, a white shark, hunting in its natural habitat, mistook Al for a meal … or maybe for competition. It bit into his leg, and its razor sharp teeth inflicted instant irreparable damage. The shark, immediately realizing its mistake, vanished back into the depths, but humans are foreigners to this sometimes violent world, and our soft bodies are not designed to avoid or withstand the investigative bite of a toothy fish that can be 18 feet long with the girth of a mini cooper. The shark wanted a tuna, not a man, but the man paid the price for the aberration.

Al surfaced and yelled the word that every waterman dreads hearing when there is a tinge of panic associated with it, “Shark!” His son, Al Junior, who was nine at the time ran to the back of the boat for help. Al yelled one final word, knowing he had been hit and his blood was draining through a severed femoral artery in his leg,”Tourniquet!” The crew pulled him onboard, but the blood loss was too severe. An adult male has between four to six liters of blood, and the heart pumps about five to seven liter per minute. The math on that isn’t promising when the main circuitry is severed, and blood pours out of the body instead of circulating within. When Al was pulled on board, he was already unconscious. Minutes later he was gone. Al Junior remembers little of the trip back to San Diego, 150 miles of open ocean. On the big boats, we take now that trip is 18 hours in good conditions. It took them 24. Al Junior has never been back to Guadalupe.

Today Guadalupe Island is renowned as a hot spot for great white shark ecotourism and scientific research. I’ve been there many times, I’ve written stories about it. A large volcanic island surrounded by clear deep blue waters teeming with big white sharks. The reason the sharks show up to the island every August to November is to feast on pinnipeds…and tuna. The area is a National Park, and visitors are now only allowed to dive in cages … unless they are on a special scientific permit assigned by the Mexican government. The permits are there to protect the sharks as much as the humans. In today’s social-media-happy world, I shudder at the thought of how many people would jump at the chance to ride the dorsal fin of a great white without any working knowledge of that particular animal’s habits or personality. Yes, they all have unique and distinct personalities.

My trips to Guadalupe are actually how Al Junior and I became friends. A few years back I was looking for someone to teach me to spearfish and free dive. A friend gave me Al’s number, and after a few quick texts the timing didn’t work out. Several months later I posted some of my white shark photos from Guadalupe on social media. I immediately received a text asking about them. How long had I been going out there? How many sharks did I see? I get a lot of questions about sharks, and I’m always happy to share big fish stories, but the next text I didn’t see coming, “My father was killed by a white shark at Guadalupe.” You’ve gotta be kidding me I thought. Is this a joke? I quickly googled Al’s name and found the headline. I stared at it for a bit before responding. What do you say? I’m sorry? How could that possibly suffice? This was the urban legend I had heard about on my trips to Guadalupe. This was the story I always chalked up to being a gruesome yarn fed to tourists when they asked about diving out of the cage. It was real. As a freediver, shark conservationist and a rather lousy beginner spearfisher, the story struck a real chord with me. I devoured information about Al Senior. I read Last of the Blue Water Hunters, a book about the beginning era of American spearfishing full of pics of Al and his buddies pulling up fish that one could only dream about today. They were the cowboys of the sea, the free-spirited mavericks that built their own equipment, taught themselves freediving techniques, wore wool sweaters before wetsuits and loved every damn minute of it. No book on spearfishing lacks mention of Al Senior or his last moments at Guadalupe. Al’s loss shook the worlds of freediving and spearfishing to the core. He was one of the most revered watermen of the era.

Al Senior wasn’t the only incident involving a spearfisherman and a white shark off Guadalupe. The pull of the giant tuna was just too great. Eleven years later Harry Ingram, a good friend of Al’s, was spearfishing the same waters. This time he saw the shark coming. He yelled, “Shark!” wanting his friends to know what killed him if it came to that. It had just taken his fish, leaving only particles of flesh floating in the water. He pointed the speargun at the charging animal and fired. The impact didn’t even slow the shark down. Luckily the gun itself acted as a pole vaulting him out of the water and out of the shark’s trajectory. The boat picked him up momentarily, and his only injury was a severely bruised shoulder from the butt of the gun and the story of a near miss that runs shivers down any divers spine. Ingram has also not returned to Guadalupe.

Other than these two confirmed reports, Mexican fishermen tell stores of abalone and urchin divers that never surfaced, stories of empty fishing boats found floating at sea. I’ve heard these urban legends on the Guadalupe cage dive boats too. Who knows, maybe they’re true as well.

As I got to know Al Junior a little better, I was struck by his passion for the ocean. He dives as much as he can, he loves teaching people to hunt elusive fish like white sea bass and tuna in the kelp beds and blue waters off Southern California … where his father loved to hunt as well … and, most amazingly, he holds no animosity toward the shark that took his fathers life. He understands the bonds to the watery world that pulled his father toward dangerous situations. His connection to the ocean is palpable. Every time I travel to dive he gets excited about my photos and is a wealth of knowledge about the fish…where they are, how to hunt them, how to cook them. We wouldn’t dream of going out to Catalina Island, one of his favorite undersea haunts, without checking in with Al to see where the yellowtail are hiding or if anyone has taken a white sea bass lately.

What Al Junior understands is that the ocean is a wild place full of wild creatures and we enter at our own risk. Those of us who love slipping below the surface sign an imaginary waiver every time we do. Realistically, our chances of getting attacked by a shark are somewhere in the one in three to ten million range … depending on the source. Either way, they are pretty slim. Fireworks or driving in Los Angeles will get you long before a shark might. What men like Al Junior know is that the magic of that silent world, the peace it brings, the exhilaration of the hunt and the direct connection to your food far outweigh any fears that linger in that most primal corner of the mind.

Tell me about your dad … Who was he? Who was he as a person, and what was the mark he left on the world of spearfishing?

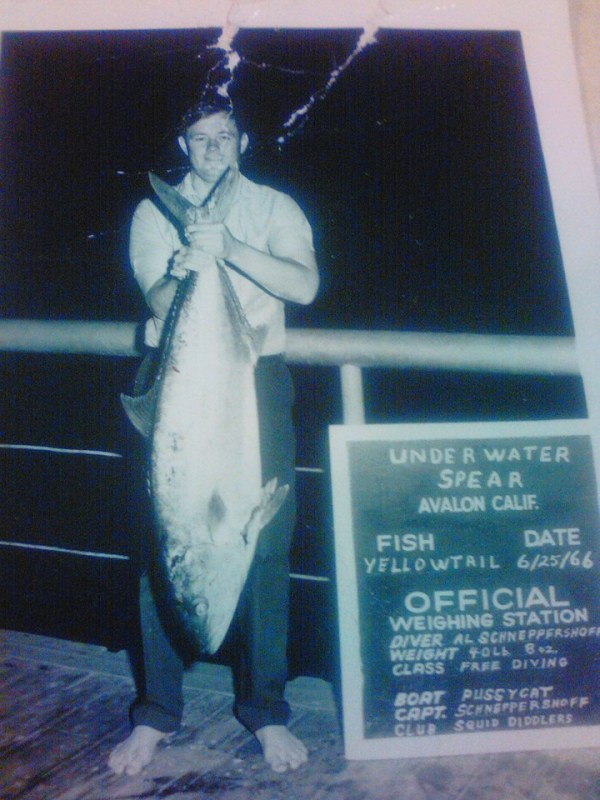

Al Schneppershoff Jr.: Well, my dad first started regular fishing with his father when he was a kid. Then, he picked up spearfishing from some of his co-workers at Hughes Aircraft in 1959.

A short time thereafter, he very quickly became a proficient spearfisherman. In my mind, he must have been born with fish sense. I say this because he would invariably find fish whenever he got in the water, if there were any fish to be found. He was always the first one in the water and the last one out. He was also known to spend more hours in the water than any other diver, seven to eight hours per day.

Some of his spearfishing achievements include: He once held the world record for black sea bass (525 lbs.); he was twice the Long Beach Neptune Blue Water Meet champion (in 1967 and 1969); in 1971, he was the Pacific Coast Spearfishing champion; and he competed in five national spearfishing championships, finishing second twice (WA and FL) and never worse than fifth.

During his diving career, he took many divers out. Everybody wanted to learn from the best. Many of the divers who he took out went on to become great divers in their own right later in their respective diving careers.

In my father’s approximately 13-year spearfishing career, he probably speared more fish than avid spearfishermen with 35- to 40-year spearfishing careers.

Some people referred to him as the “Muhammed Ali of spearfishing.” This was because even though he could be a braggart at times, he always backed up what he was bragging about.

The Long Beach Neptunes, a spearfishing club, has an award called the King Neptune. To achieve this award (after you become a member), you must shoot: a black sea bass over 100 pounds; a yellowtail over 20 pounds; and a white sea bass over 40 pounds. It has taken some members up to 15 years to accomplish receiving the King Neptune Award.

Approximately two weeks after my dad became a member, he went to Santa Cruz Island on his boat and shot a black sea bass over 400 pounds; a white sea bass over 60 pounds; and a yellowtail over 40 pounds. Getting all these fish in one day, he became the only Long Beach Neptune to get the King Neptune Award in one day. To this day, no one else has ever done this.

What are some of your favorite memories of your dad?

AS: I only got to dive with him for three short years, and this was when I was a young kid. My dad never forced me to go diving. He just said, “Here’s your gear; if you would like to learn, I will take you out.”

I remember one of the first times that I got in the water with him, I had speared a 14-inch calico bass (I was 6 years old at the time). I actually learned how to spearfish before I learned how to ride a bike.

I also remember another time when I went with him on one of his commercial abalone diving trips (I was about 8 years old). He always told me to wait until he got back before we went in the water together. I always fished when he was diving for abalone.

We were in fairly shallow water (20 feet). I could see the bottom while I was fishing. This huge calico bass swam up to my bait, looked at it and swam off. So, I decided not to listen to my father this time. I got my gear on, got in the water and proceeded to shoot three calico bass while he was still diving for abalone.

I didn’t really know what his reaction was going to be when he returned to the boat. He appeared to be more proud than angry.

From that day on, I was hooked.

What happened that day in 1973 (September 9) at Guadalupe Island?

AS: Earlier that day, we arrived at Guadalupe Island.

My father and Bob Stanberry and the other divers got in the water. My dad was the last one back to the boat. He came back to the boat very excited because he saw bluefin tunas over 200 pounds. This was why they were on this particular trip – to try to spear the big Bluefins.

Then they moved the boat to a spot where they would anchor for the evening. But they weren’t finished diving yet. Bob Stanberry had just gotten back to the boat, and my dad was still in the water. My dad was always the last one out of the water.

A few hours later, I was on the bow of the boat watching my dad dive. All of a sudden, he came up out of the water, yelling, “Shark! Shark!”

I ran to the back of the boat to tell the others what he was saying.

One of the deckhands of the boat ran to the front of the boat and threw the anchor line off the bow of the boat that was attached to a buoy.

They quickly pulled the boat up to where my dad was. As they were pulling him up on the deck, he said the word, “Tourniquet.”

At this time, I don’t think he realized this was going to be his last word spoken.

When they got him on the boat, he was already bled out because the shark got him in his calf and caught the main femoral artery.

It was a tough 24-hour boat ride back to San Diego.

One thing that this accident did for the next generation of blue water hunters was that they always dove in pairs and they had chase boats in the water.

How long was it before you got in the water again?

AS: I was nine years old when my dad was killed by the white shark. It took me about two and a half years to get back in the water. One of my father’s best friends, Gary Thompson, kind of took me under his wings and became kind of a surrogate father. He helped me get back in the water.

I ended up diving with Gary until I was about 16 when I got a driver’s license. Once I could drive, you couldn’t keep me out of the water. Gary and I continued to dive together over the years, and we were teammates in numerous Pacific Coast spearfishing championships. Our team (Gary, me and Rene Rojas) took first place in the 1987 Pacific Coast championships. Gary was first individually, and I was second. The Pacific Coast championship trophy for the individual winner is dedicated to my father.

How were you able to find peace with what happened and not fault the ocean, sharks or the sport of spearfishing?

AS: First of all, my being there on the boat when my father was killed and witnessing what happened gave me closure about the incident that I wouldn’t have had if this had not been the case. My grandmother (my dad’s mother) and my mother never got over it.

As I got older, I started diving with people who dove with my father. I got to hear from them some of the lore about who he was, how he acted, how he was in the water, his personality when he was diving and so forth. He was really one of the first true “blue water hunters.” He had a big personality, and people either loved him or … Well, most people loved him.

My understanding is that he “pushed the envelope” with regard to the sport of spearfishing. It is also my understanding that because he was pushing the envelope, he was putting himself at a higher risk than most other divers.

I remember one incident when I was about eight and a half. We were a few miles off the back side of Catalina Island. My dad was looking at spearing a swordfish. My dad and his diving partner, Buzz Patterson, found one sunning on the surface of the water.

My dad, with his gear on, decided that he was going to try and go spear this swordfish.

He got in the water, he was swimming towards the swordfish, and as the swordfish was swimming away, we maneuvered the boat so that the swordfish would swim towards my father.

But the swordfish was smarter than anyone thought and swam under the boat, and my dad never got the opportunity to get a shot off. Looking back on it, I’m glad because I’ve since heard stores that spearing or trying to spear a swordfish can be deadly.

What do you do now? Tell me about your personal passion for the ocean and spearfishing.

AS: I have been teaching spearfishing for over twenty years, and for fifteen years, I ran trips down to Baja, California with spearfishermen and women who wanted the opportunity to learn in a few days what it would take to learn here in Los Angeles two to three years.

I have speared a lot of fish in my lifetime, including white sea bass, yellowtail, groupers and others.

Now, I get a great thrill teaching other divers how to be safe and spearfish that they have never been able to spear before.

Do you worry about sharks when you dive?

AS: I don’t really think about sharks when I am in the water. I do, however, know quite a few ways to substantially reduce the risk of getting attacked by a shark, and I follow those guidelines. For one thing, I don’t dive around Northern California, especially in what’s known as the “Red Triangle.” Also, I would obviously never dive Guadalupe Island.

I tell my students who I am teaching that you have a better chance of being killed driving to the dive site than being killed by a shark.

I feel as though if you stay in the thick kelp beds, a big shark probably won’t go into that kelp.

Also, if you stay away from places that have a lot of seals, then you are probably pretty safe.

What are some of your favorite ocean moments?

AS: I have run countless trips down to Turtle Bay in Baja, California, taking divers of varying levels of proficiency. I’ve had beginner spearfishermen go to Baja with me and spear their first yellowtail or their biggest yellowtail on my trips. I really love to see their excitement after they’ve landed these fish.

A few of my own personal experiences down in Baja:

On one particular trip, we were diving off the beach, and four of us swam out to the reef. I was in the water for maybe ten minutes, and I ended up spearing a gulf grouper in about twelve feet of water. That was a very big fish for such shallow water.

On another trip to Baja, I took a group of divers. One of the divers who I took speared his personal best yellowtail and broomtail grouper on this trip. The yellowtail was 48 pounds, and the grouper was 72 pounds. On this trip, I happened to get a 93-pound broomtail grouper (my personal best grouper).

I have speared more white sea bass than I like to talk about, but my five biggest have all come from Turtle Bay (Bahia Tortugas) in Baja, California. The biggest was 72 pounds.

On one trip, I took a friend of mine, Joe, down to Punta Eugenia. When we got out to the yellowtail spot, Joe jumped into the water, swam about twenty feet, dove down and shot a 49-pound yellowtail. He swam back to the boat with the fish, threw the fish in the boat, climbed in and said, “I’m done.”

Some of my fondest memories of spearing fish in California include:

When I was 20, I lived on Catalina Island for three months. That Summer (of 1983), I ended up spearing 22 yellowtails, 13 white sea bass, 10 halibut and many miscellaneous other fish.

I have spent many years spearfishing around the Palos Verdes Peninsula. It’s one of my favorite places to hunt for white sea bass. I have had days when I’ve speared fish over 50 pounds. Currently, I have a favorite place where I take beginners to hunt for their first white sea bass.

What would you like for people who are not ocean savvy to understand about sharks?

AS: In my spearfishing career, I have spent around 5,000 days in the water all over Southern California and Baja, California, and I’ve actually never seen a shark larger than ten feet; and furthermore, I have never seen a great white shark. That does not mean that they are not out there. But I don’t spend my time worrying about running into Great White sharks while spearfishing in Southern California.

There are a lot of other ways that you can be hurt or killed not going in the ocean. In my mind, I feel safer going in the water than being on the land.

Why is ocean conservation an important issue for you, and why do more people need to worry about it?

AS: For starters, spearfishermen should only spear what they are going to eat. There is no reason to take more fish than you need or are going to use.

One thing that I try to teach my students is that a yellowtail is a fast-growing fish. They only live to about nine years. They multiply quickly, and they procreate in great numbers. So, taking one or two of these per dive is not going to hurt the yellowtail population.

On the other hand, regarding sheepshead: I try to educate my students that a 25-pound sheepshead is around 55 years old. So, I want the divers to know that if you take multiple 25-pound sheepshead out of the water, you’ve just taken 100- to 150-years of fish out of the ocean. I personally think a 4- to 10-pound sheepshead tastes better anyway.

White sea bass live to about 30 years. A 60-pound white sea bass is about 20 years old. Between March 15 and June 15 is the time that they are spawning. That’s why the limit is only one per day during this period.

I try to teach my students to make an effort to go after faster-growing fish, like the yellowtail, dorado, etc.

In the most recent text exchange, we had Al promised to get me hunting yellowtail and white sea bass. His text read, “I was born to put divers on fish.” This makes me very happy indeed.

Al Schneppershoff Jr. is a spearfishing guide based in Southern California. His contact for anyone interested in the art of the underwater hunt is (424) 222-1011.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.