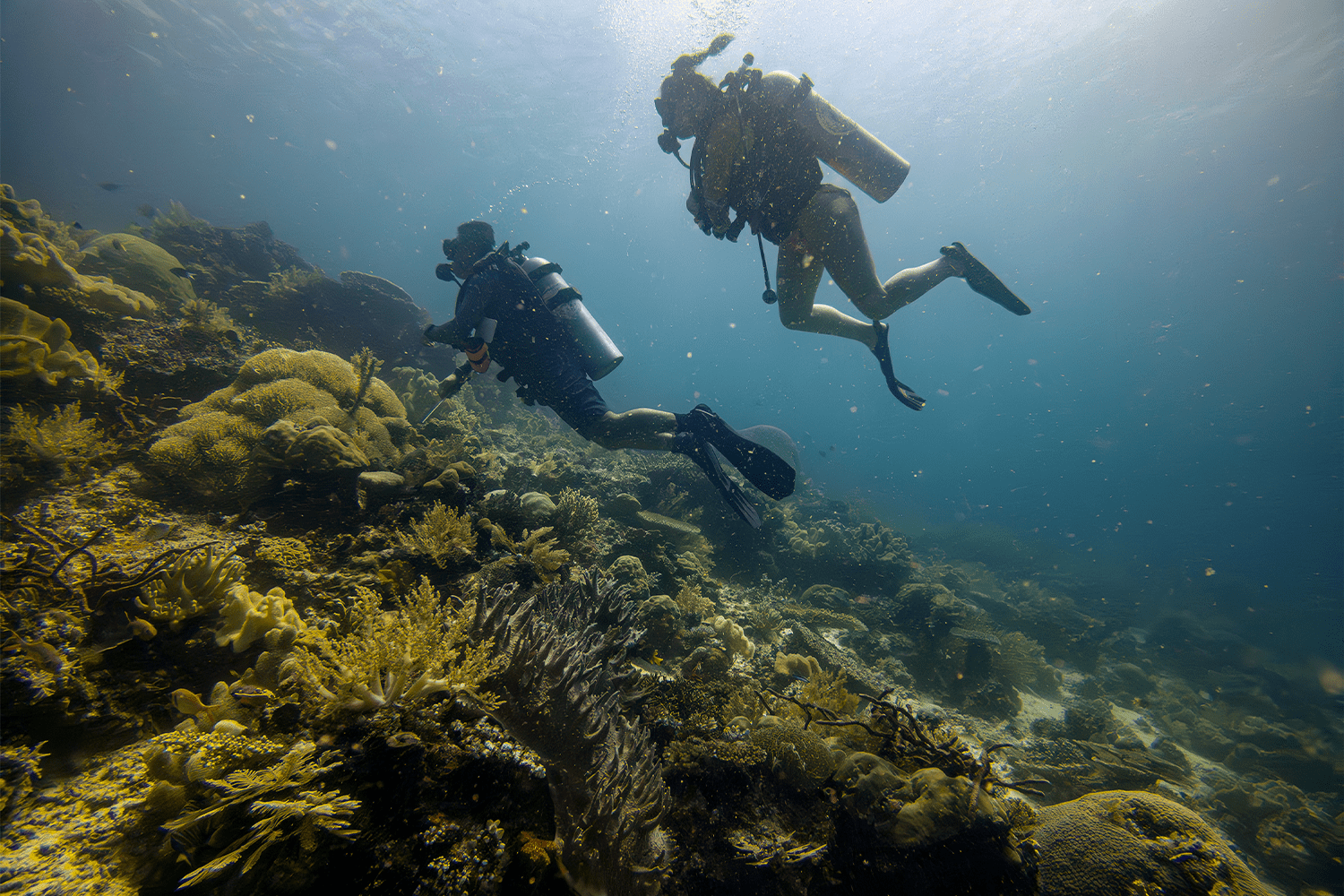

Scuba diving off Mioskon, a minuscule islet in Indonesia’s far-flung Raja Ampat archipelago, I’m staring in disbelief at the wildy-colored hard and soft corals populating a gently-sloping reef. From pale brown finger corals reaching up to the sky and huge, aptly-named brain coral to staghorn coral and deep red fan coral, I feel like I’ve stumbled on an underwater garden of Eden.

A Titan triggerfish hovers a few feet below; I can’t take my eyes off its yellow and black patterns. The solitary creature pauses and looks at me. All of a sudden, it charges upward and menacingly taps its snout on my dive buddy’s GoPro lens, as if to shout “Get outta here!” before whooshing back down. With teeth powerful enough to crush and eat coral, this isn’t a fish to be messed with. It has been known to bite divers.

As dive instructor Steve “Roy” Royin explains when I climb back onboard Indonesian Phinisi schooner Prana by Atzaró, this tough-as-nails reef dweller is highly territorial. “It was probably defending its nest,” he says. Next time I find myself in a Titan triggerfish neighborhood, I may consider neck-to-ankle neoprene rather than a simple rash guard.

I’m diving in one of the world’s marine biodiversity hotspots. Raja Ampat lies off the west coast of the island of New Guinea, which is divided between Indonesia and Papua New Guinea. Four main islands make up Raja Ampat, which translates to “four kings,” namely Waigeo, Batanta, Salawati and Misool. Spanning 44,000 square miles, there are more than 1,500 small islands, cays and shoals here in the heart of the Coral Triangle where the Pacific and Indian Oceans meet. Some 76% of all known coral species are found here. More than 1,638 species of reef fish reside in Raja Ampat, along with some 600 types of coral and 700 types of molluscs.

Teeming with plankton and other nutrients, Raja Ampat is home to marine life including shy Wobbegong sharks, giant manta rays, whitetip and blacktip reef sharks, and hawksbill turtles. Among endemic species is the curious epaulette — or walking shark — which uses its pelvic and pectoral fins to “walk” on the seafloor, particularly in shallow waters.

This Is No Liveaboard

After flying on two hours of sleep from Jakarta to the West Papua province city of Sorong (the gateway to Raja Ampat) the previous morning, I step aboard Prana. It is named after a Sanskrit term meaning “primary energy,” frequently translated to “breath” or “vital force.” Considered the largest and most luxurious of the two-masted Phinisi schooners plying these waters, Prana is not merely a pretty boat.

Artisan boatbuilders in Indonesia’s South Sulawesi province, the Bugis people specifically, continue to proudly craft these commanding beauties by hand, using ironwood and teak but, incredulously, no nails. Traditional methods, which entail rituals and ceremonies, are strictly followed to create this Indonesian seafaring icon. Originally used for fishing and goods transportation, with cargo carried in the hull, these days many Phinisi boats serve as liveaboards, bookable by cabin that cater to divers who travel from all over the world to explore this astounding underwater world. But Prana is no liveaboard.

Fashioned by the founders of Ibiza-based, five-star hospitality brand Atzaró Group, Prana is a Sulawesi-built luxury private yacht available for charter, hosting up to 18 guests in nine suites. Tradition and modern-day comforts blend in the best possible way. Plush accommodations are paired with high-end onboard service. At 180-feet long and a beamy 36-feet wide, there are plenty of spaces for reading a book, sipping on a sundowner or simply lounging around, from the voluminous saloon to enticing day beds on the main deck.

Before I head below the sea surface, I check into my surprisingly spacious quarters on the lower deck. Named Komodo after the island home of the world’s largest lizards and Prana sailing grounds, my cabin is comparable to a high-end hotel suite, comfort-wise. But it’s much more homier. Materials used, like solid teak, serve as a respectful nod to Phinisi tradition and craftsmanship.

Beamed wooden ceilings tower over a sprawling king bed dressed in neutral hues, and there’s even a handy desk. In the bathroom, there are twin marble sinks, a roomy shower with two rain shower heads and invigorating cosmetics from Balinese company Republic of Soap, including a vitamin C-infused face serum and reef-friendly sunscreen. What captures my attention, though, are the elaborate tribal headdresses on display. Fashioned with shells, feathers and organic fibers, they hail from the Asmat tribes, once feared headhunters and cannibals, residing in Indonesia’s easternmost province Papua. A monochromatic photograph depicting an Asmat warrior wearing a fur headpiece lined with tiny cowrie shells is nothing short of mesmerizing. A large carved shell ornament representing the curled tail of the cuscus, an Australasian marsupial, pierces his nasal septum. But his liquid olive eyes exude a deep gentleness.

Five Days on a Catamaran in the British Virgin Islands

How one trip with The Moorings altered our perception of vacations, maybe forever

Cry Me a River

Cruise director Michael Wronski informs us we’ll be sailing through the Dampier Strait, known for its rich marine life, in the vicinity of Waigeo and surrounding islets, where sea temperatures remain a comfortable 82 degrees year-round. The first order of the day aboard Prana entails a lavish breakfast in the indoor dining room, whose tall windows offer soothing sea views. Chef Teguh dishes out culinary miracles from his diminutive galley. Bright purple dragon fruit, papaya, mango, chia pudding, stir-fried tempeh and energizing mie goreng (a stir-fried noodle dish) count among the morning delights.

Chatting with effusive Balinese crew member Maria about Indonesian produce, I show her photos of a purple-grey tropical fruit I sampled during a jet lag-allaying 24-hour layover at The Orient Jakarta in Indonesia’s capital. “That’s snakeskin fruit,” she explains. “Have you tried the smelly fruit?” she asks, referring to durian. Not yet but it’s on my list. For now, I throw back a brain-perking ginger shot, excited for the undersea adventures to come.

In Raja Ampat, there are no upscale resorts, sleek restaurants or cocktail bars. A handful of dive lodges and homestays are spread out across the islands, with opportunities for divers and snorkelers to get out and explore. For nature enthusiasts and bird-watchers, it’s considered one of the last slices of earthly paradise.

To safeguard the long-term health of these delicate marine ecosystems, the Indonesian government established a network of seven Marine Protected Areas (MPA) in 2007. With significant increases in visitors during the past decade, most of whom book dive trips on an ever-growing number of Phinisi liveaboards, the Indonesian government has sought to prioritize sustainable tourism. The Raja Ampat MPA Network has introduced regulations such as a limit on the number of dive boats in the MPAs at any time and a diver code of conduct.

Beyond the exquisite diving, Raja Ampat reserves other surprises. Our first stop sees us drop anchor near Mayalibit Bay, off Waigeo’s southern coast. There, we don rash guards and dive booties and step into a tender helmed by Roy. He takes us flying through a river past mangrove forest where clouds hang low and heavy. We make a stop at a jetty in Warsambin, an isolated village with a population of about 1,000, to pick up indigenous Maya tribe members Amos and Jessica, who are in ceremonial paint and dress.

Disembarking from the boat, we set out on a river trek, with Amos and Jessica leading the way, barefoot. “Are there sea snakes or crocodiles here?” I ask Roy, eyeing the opaque bottle-green waters. He laughs, saying “I’ve seen saltwater crocodiles in Raja Ampat but not around here.”

We slosh our way through mid-shin deep water. I pause to listen to the melodic bird call echoing amid the treetops, wondering if it’s a cendrawasih merah, Papua’s revered red bird of paradise. Papuans believe they are fairies reincarnated. If you’ve ever seen a vividly-colored male cendrawasih merah perform a showy dance for a female, you’ll understand why. The province plays host to no less than 37 of a total 41 cendrawasih species found in Indonesia. Listed as a threatened species, they face danger from poachers and habitat loss caused by logging, agriculture and development. “What you can hear are hornbills, cockatoos and birds of paradise,” Roy says.

Once we reach dry land, a winding trail passes through the dense Waisai rainforest and leads to an oasis: Kali Biru, a luminous electric blue, translucent freshwater river with a white sandy bottom. We take turns jumping off a wooden platform, feet-first into the cool water and revel in this watery wonderland.

Back on board, we wind down over a spicy Thai dinner and toast with cocktails on the top deck as the sun sets and a cloud-streaked sky imitates the astonishing blues of Kali Biru.

The Wonders of Sawandarek

On day two, we arrive at one of Raja Ampat’s most beloved dive sites. Surprisingly, it’s a jetty. Prana moors at Sawandarek village, off the south coast of Mansuar island. Fortunately, we’re the only visitors.

I mask up and gradually descend into the deep, guided by Roy. Considering I had last dived when I gained my PADI Open Water Diver credentials some two decades ago, I’m amazed at how comfortable I feel in unfamiliar waters so far from home. A quick PADI refresher course a few days before flying to Raja Ampat proved useful. But, in real world circumstances, it is Roy who makes me feel confident and completely at ease.

Just off Sawandarek jetty lies an expansive reef teeming with all manner of undersea life. Blessed with startling clear waters, we spy yellowfin surgeonfish, one spot foxface rabbitfish, Bengal sergeant fish and tall slender-bodied Batavia spadefish. A school of long, thin pickhandle barracuda swims by, unperturbed by our presence. Looking down at the sea bottom, we spot two large green turtles resting. Occasionally, they peer up, shyly batting their eyelids, so we keep a significant distance.

While there seems to be an abundance of soft and hard coral here, restoration efforts are key to keeping the reef healthy. Roy points out a budding coral garden. “Corals grow just over half an inch a year, so it’s a long, slow process,” he says. “That is another reason we have to be very careful when diving, to ensure we don’t brush up against coral and risk damaging it.”

Post-dive, we walk around the village’s freshly-groomed sandy pathways and watch local youngsters emerge, gleaming, from the sea, thrilled to help their fathers haul in the day’s catch. One poker-faced youngster no more than eight years old holds a tuna in each hand. “That’s dinner!” Roy exclaims. Villager Eddie tells me locals are permitted to fish, but they need to stay a minimum of 1.2 miles from the shore, as Mansuar falls within a national marine park. Others squeal as they leap off the jetty in their clothes or entertain themselves with a sand bath. I momentarily envy the simplicity of their lives.

“The kids here want to go to the city,” Roy says, who notes there is an elementary and junior high school on the island.

Back on Prana, I’m relieved to find that even Starlink can’t contend with Raja Ampat’s remoteness. It feels as if nature here is forcing you to disconnect with technology, crying “Look at me! Absorb me (while you can).” In this glorious part of the world, why would you do anything else? So, I put my phone aside and plunge into deep conversation over dinner with my onboard company as tropical rain pelts down around us.

Showers fail to dampen our enthusiasm when we reach Piaynemo, a cluster of verdant islets that forms part of a newly-classified Unesco Global Geopark, of which Indonesians are rightly proud. It’s even featured on the 100,000 Indonesian rupiah bill. If you Google Raja Ampat, this is the first image you’ll see. Made of karstic limestone dating back some 400 million years — nearly one-tenth the age of the Earth — they float above emerald seas, like a vision from a dream.

An Undersea Black Forest

One morning, sunlight streams into my cabin through the brass porthole, awakening me to yet another unimaginable sight. We’re anchored off Wofoh, a pair of tiny islets draped with palm trees and linked by a reef. Each reveals a platinum blond sand beach washed by shallow aquamarine seas. Little did I know I would be dancing on one of those beaches in the evening, following an oceanfront dinner.

During breakfast, server Jay brings out a live lobster to show us what’s on the menu that day. But I’m more interested in seeing what lies west of Wofoh. Soon enough, I’m in my dive kit, flipping off the edge of a tender into the ocean.

Roy introduces me to the subaquatic Black Forest, named for the black coral found there. “There used to be more black coral, but bleaching has meant there is less now,” he says. Rising temperatures and ocean acidification has caused coral bleaching here and elsewhere in the archipelago. The good news is scientists have found that some coral species in Raja Ampat may be more resistant to increasing ocean temperatures caused by climate change.

Without coral, species like the pygmy seahorse — which Roy’s expert eye detected camouflaged amid a blue and white gorgonian seafan — would face a dire future. As we continue along a steep reef wall, I gawp at countless fish, among them Napoleon wrasse, brown-marbled grouper and various vibrant species of parrotfish.

On our second dive that day, there is less clarity. Looking at the vertical drop into nothingness, I feel slightly vulnerable, imagining an enormous squid appearing out of nowhere. So, I sneak in between Roy and the reef wall, which is covered in violet and bright orange coral, putting him on “the biting end.” A whitetip reef shark, which tend not to be aggressive toward humans, shimmies slowly in the distance. There is absolutely nothing to fear down here.

With the rest of the world switched off, I finally tune in to a rare moment of silence, a moment to receive this divine gift of nature. As we wrap up our final dive and slowly head back up to the surface, I jokingly motion to Roy, “No, not yet.” How I wish I could grow a set of gills and hang out a little longer with Raja Ampat’s weird and wonderful creatures of the deep, even if it means suffering a nip or two in the process.

The Details

How to get there: Qatar and Etihad fly daily from JFK and LAX to Jakarta. Garuda Indonesia connects Jakarta with Sorong.

What it costs to charter Prana: From $18,000 per night for up to 18 guests, including meals, drinks, one massage or beauty treatment per person, diving, watersports, excursion and guide fees and gratuities.

Where it sails: Raja Ampat, Komodo and the Spice Islands

For more, visit pranabyatzaro.com

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.

![[L-R] Bill Berry, Michael Stipe, Mike Mills and Peter Buck of R.E.M. at the Aragon Ballroom in Chicago, Illinois on July 7, 1984.](https://www.insidehook.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/rem-book-interview.jpg?resize=450%2C450)

![[L-R] Bill Berry, Michael Stipe, Mike Mills and Peter Buck of R.E.M. at the Aragon Ballroom in Chicago, Illinois on July 7, 1984.](https://www.insidehook.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/rem-book-interview.jpg?resize=750%2C500)