Sharks are undeniably fearsome predators, but are people more afraid of shark attacks than they need to be?

No other country on the planet has more shark attacks than the United States, averaging 48 per year. Although none were fatal, there were 53 bites in American waters in 2016. According to the International Shark Attack File (ISAF), 35 bites alone were reported last year in Florida, where there’s the highest concentration of attacks in the world.

While Florida’s home to the most bites, South Africa and Australia tend to have more fatal attacks. Two of the four fatalities worldwide in 2016 were in Australia, according to the ISAF. Each year, there’s an average of eight fatal shark attacks worldwide.

Considering the millions of people swimming last year, the odds are certainly favorable. George Burgess, the curator of the International Shark Attack File, says the stat “puts in perspective what the relative risk is of shark attacks.” As unlikely as they are, bites are still on the rise.

Each decade has seen more shark attacks than the last. The most attacks on record (98) occurred in 2015. Buress attributes this to warmer waters caused by El Niño. As the temperature increases, the range of sharks expands and, with it, the number of people hitting the beach. If global population continues to rise, Buress anticipates the number of shark bites will continue to increase and climate change is likely to compound the trend.

Despite the rise in attacks, the number of deaths consistently decrease because of better medical care, greater vigilance on beaches, and increased awareness about shark safety. Collectively, this has brought the risk of fatality down to less than five percent. That makes the odds of dying in shark attack about one in 3.7 million, according to the ISAF. In fact, people are 3,000 times more likely to drown at the beach during their lifetime than being killed by a shark. The odds of getting pulverized by an asteroid are also higher, one in 1.6 million, according to a Tulane University study.

If the risk is so low, then why are they still terrified of sharks? It’s complicated, but the short is part biology and part society. Human brains are hardwired to respond to emotion first before reason. It’s also fueled by the media coverage of shark attacks, which Burress says isn’t commensurate with the risk.

Alarming headlines fuel “availability bias,” or the inclination to favor what’s most easily remembered. For example, wall-to-wall coverage of terrorist attacks tends to make people fear them more. When UCLA researchers examined stress levels in victims of the Boston bombings in 2013 and in people that repeatedly read news coverage of the attacks, they found “[r]epeated bombing-related media exposure was associated with higher acute stress than was direct exposure.”

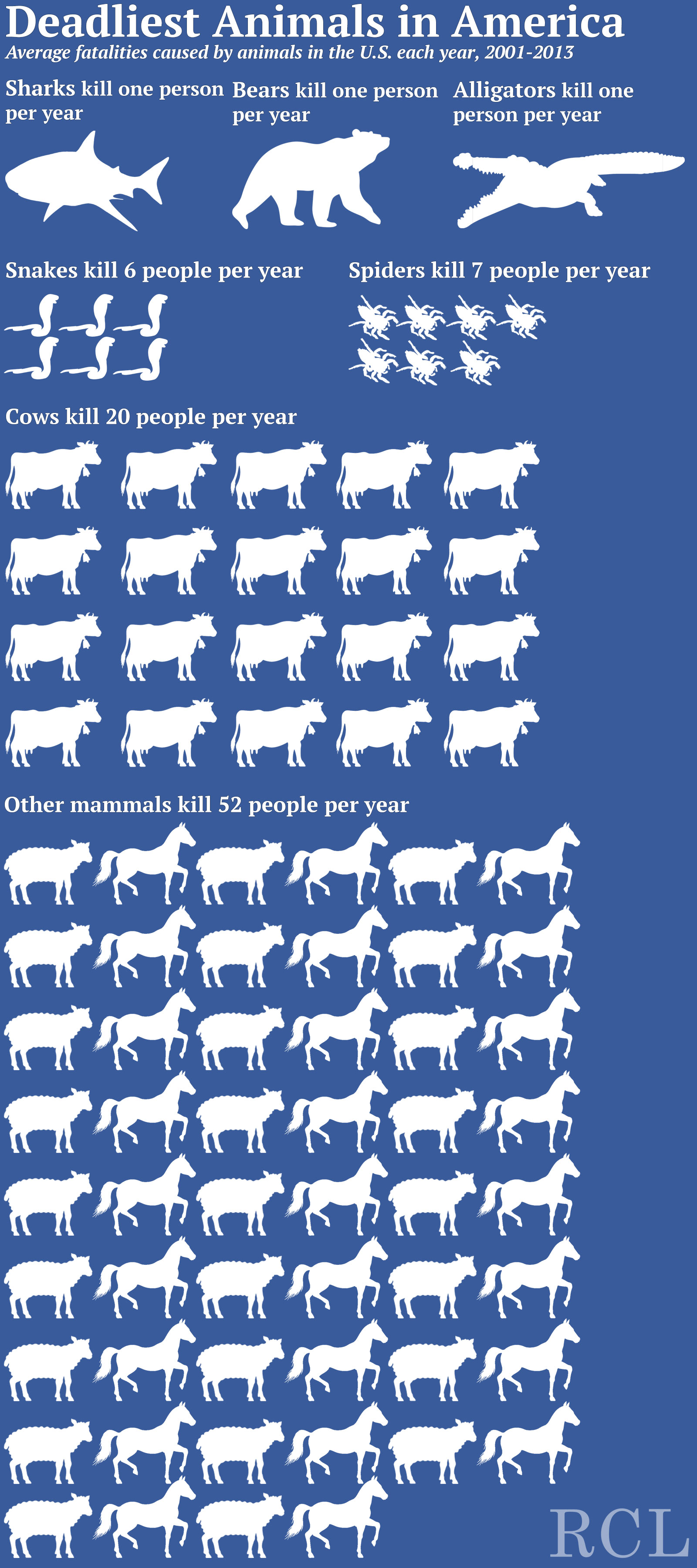

This could explain why a Chapman University Survey of American Fears last year that 41 percent of Americans are most afraid of a terrorist attack. It’s understandable given the spate of headline-grabbing ISIS attacks in 2016. Still, the odds of being killed by a terrorist each year is one in 3.6 million, according to a recent Cato Institute report. The truth is Americans far more likely to die from the things fear least, like cows.

It wouldn’t be too surprising to have a nightmare about being killed by a shark or a terrorist, but no one is losing sleep over toddlers with guns or falling out of bed. According to a decades-worth of data from the Centers for Disease Control, each year an average of 11,737 Americans are fatally shot (21 of whom by toddlers) and 737 people die falling out of their bed. Over the last ten years, an average of six people a year were killed by sharks worldwide.

“The real story isn’t that shark bites man is that man bites shark,” Buress says. Each year, fisheries kill between 30 to 70 million sharks. Some estimates are as high as 100 million, National Geographic reports. Rounding up the average deaths to ten, the ratio of shark deaths to human deaths is tens of millions to one.

So, who’s threat real threat? “Sharks have a lot more to fear from humans than humans fear from sharks,” Buress says.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.