“Mr. Jeff, would you like to ride a camel?,” my guide Ikram asked while waiting outside my yurt. Oh goodness, I thought to myself, is there anything more embarrassingly touristy than perching yourself on top of a swaying camel while the local camel driver leads you around in a circle for a photo op?

But here I was in the Kyzle-Kum desert near the Kazakh border, morning sun turning the sandy hills gold, the Silk Road not far off. And those irresistible camels with their droopy lips, goofy smiles, pie crust hoofs and colorful saddles were waiting for me. Yes, Ikram, I would like to ride a camel.

Ah, the Silk Road. Ancient travelers, spices, fabrics, dozens of languages, exotic cities — you come back from visiting these places and, well, you feel like you’ve been somewhere. You can now casually drop phrases like, “Yeah, I’ve seen Samarkand” into conversations.

For the uninitiated, the Silk Road, a name coined in the 19th century, was not a specific road but a network of trade routes that ebbed and flowed for nearly 1,500 years between China and the Mediterranean. Uzbekistan is one of many countries with a Silk Road history, and with some of the best preserved sights from the glory days of the 13th and 14th century Mongol Empire, it’s become the most visited country in Central Asia.

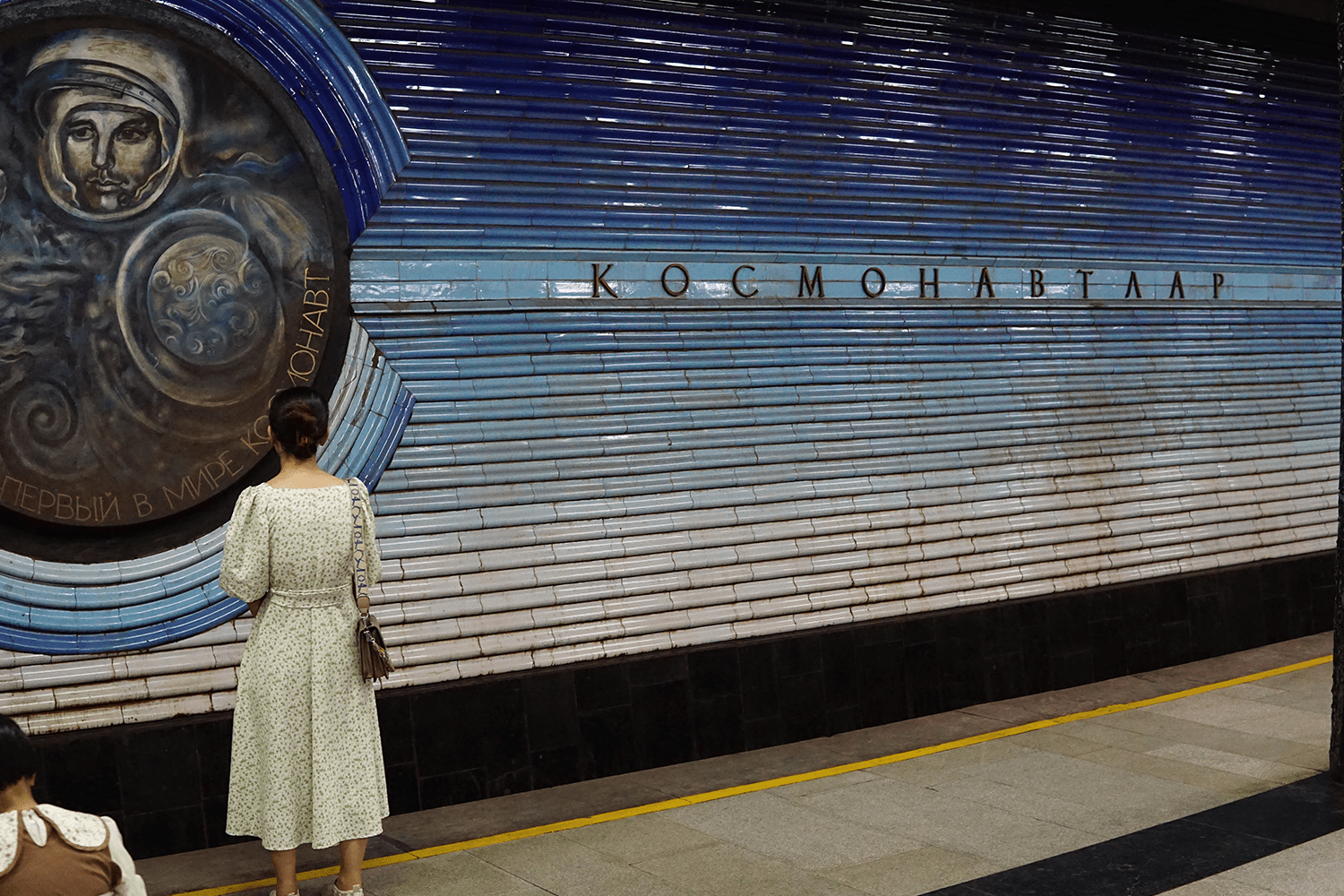

My first visit is to a metal road, the Tashkent Metro. Fifteen cents is all it costs to take a ride through Tashkent’s gorgeous metro stations, each one featuring a different theme. My favorite is the spacey blues of the Kosmoanovtalar station with giant portraits honoring early Soviet cosmonauts.

From Tashkent, I take the high-speed Afrosiyab train to Samarkand where I enter the fabulous turquoise and gold worlds of what I start calling the “3 M’s”: madrassas, mosques and mausoleums. It’s a delightful overload of intricate detail work and grand architecture restored in the 20th century and now gleaming for centuries to come.

Samarkand’s top sight and, I’d say, one of the great sights of the world, is the Registan. Three madrassas (an Arabic term for school) built in the Persian style between the 13th and 15th centuries frame an enormous public square. According to at least one travel blog, guards sometimes let you climb one of the off-limits minarets for a “fee.” Sure enough, the next morning, standing outside the fence taking some photos, I see a guard ambling towards me. He pushes open a section of the fence, points to a minaret and says I can climb it. How much? Fifty thousand Uzbeki som.

Thanks to one of the most lopsided exchange rates in the world, I happily pay just less than $4 for the guard to slip me through the ancient wooden door of the minaret using an even more ancient looking key and usher me up the winding stairs for a glorious morning view.

Having bribed my way into seeing one more “M” — a minaret — it’s time to leave the cities and set off into the desert. Yurts and camels. My hired driver and guide, Ikram from Nuratau Travel, picks me up in Samarkand. Nuratau offers a variety of daily and weekly tours from horseback riding to homestays. Attracted to a “harmonious blend of history and nature” as marketed on their website, I choose the desert yurt camp overnight adventure.

This Stunning Silk Road Country Should Be on Your Travel List

Uzbekistan was once the heart of the ancient trading route between China and the MediterraneanMy first experience with the promised blend of history and nature is persistent rain. Comfortable in the back seat of Ikram’s car, reading and resting, letting him deal with the puddles and potholes, I feel a little guilty. This is not how 14th century travelers did it. But Ikram feels pretty authentic. He speaks Uzbek, Tajik, Russian, decent English, knows every kilometer of the roads and, it seems, most of the people. As we drive, he points out notable sites, relates the history of the various towns we pass through and takes me to a homemade lunch spot without a sign on the edge of the desert. I wouldn’t be surprised if Ikram could lead a camel caravan himself and maybe even fend off some Silk Road bandits while he’s at it.

Hours later, night falling and after several final kilometers on a questionable muddy dirt road, we arrive at the yurts. I join up with a jolly group of 12 German tourists who, unfazed by the dreary rain, are drinking some non-Silk Road looking schnapps. Ikram points out my assigned yurt, and I walk over and peer through the wooden door. With an outer covering of overlapping cloth, including felt and animal skins, the inside is dry, with enough room for three squat bed frames, each piled with blankets and a pillow. I flop down to test one of the beds. Not bad. Gazing up, listening to the rain, I can see the thin wooden supporting bones of the yurt.

Soon I hear a call for the evening meal inside a nearby dining area. The rain precludes dinner around the campfire, but we still enjoy dimlama, a traditional meat and vegetable stew, along with salads, bread and copious amounts of tea and juice. As we finish our meals, an elderly fellow shuffles in with a do’mbira (a long necked Khazah version of the guitar) and strums a few strings. The German chatter eases and he then launches into a series of melancholy folk songs. They all sound similar to me, making me think of desert expanses and ancient stories.

A short time later, I step outside the dining area to the comparative quiet outside. The rain has slowed, and is that a star or two on the horizon, dim behind thin clouds in the cooling 50 degree air? After a quick stop at the shared bathroom, I slip back into my yurt and nestle under the felt and wool blankets listening to slowly fading drips of rain.

Morning in the Uzbek desert, a low sun in the sky, just a few clouds remaining, I step out of my yurt. No one else is around, and I head out for a walk, carefully marking my path among the sandy hills and low vegetation. I come upon some cows munching on tiny tufts of grass and then, a few minutes later, I delight to see several shaggy Bactrian (two humped) camels among the desert scrub. How lucky is this? I am in the heart of the desert, I spent the night in a yurt and now I come upon some wild camels?

I retrace the path back to the encampment, eat some breakfast and that’s when Ikram asks me about a camel ride. We walk over and I see the same “wild” camels I saw earlier, now with saddles and reins. So much for my wild camel experience. Touristy it may be, but I take great delight in riding the camel for 20 minutes through the desert scrub, accompanied by jingling bells and camel snorts.

Soon I am back in Ikram’s car, headed to Bukhara. We make a lunch stop by gleaming Lake Aydarkul and then the city of Nurota, where I explore the supposed and well-weathered ruins of one of Alexander the Great´s fortresses. My desert adventure comes to a close as we approach Bukhara, my last stop of the trip, another enchanting Silk Road city, filled with more madrassas and mosques to marvel at. I can imagine weary travelers from the past, grateful to escape the desert for a time, relieved to have reached a city, the end of a journey.

I can understand that, especially as I enjoy the Ark of Bukhara, the Kalyan Minaret and eat Uzbeki osh, but desert dreams of yurts and camels stay with me to the end.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.