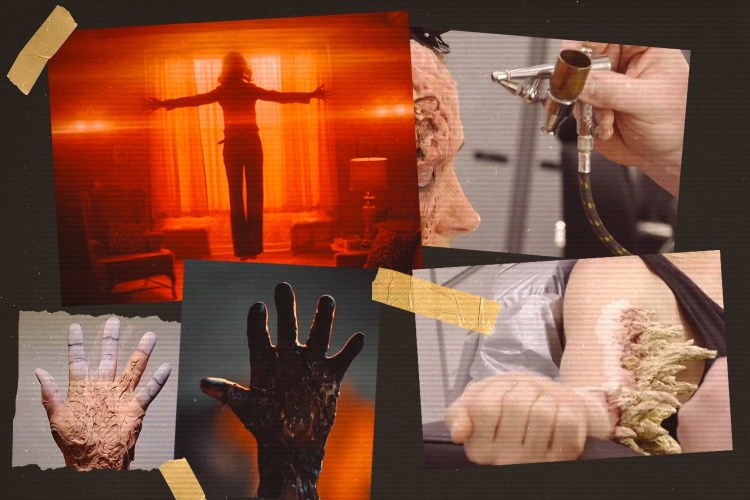

There are more than 75,000 different plant species that grow in the Amazon. But it is the particular combination of one of the region’s species of vine (Banisteriopsis caapi) with one of its species of leaf (Psychotria viridis) that now draws thousands of tourists to South America each year. They are all looking to experience ayahuasca, the powerful psychoactive brew that native Amazonian tribes consider an all-encompassing healing medicine.

But as ayahuasca’s popularity has mushroomed, so too have the dangers associated with taking it. Shady purveyors of the drug now operate amidst the legitimate shaman who dispense it with care. Likewise, fatal drug interactions (particularly when tobacco, stimulants, or other substances are taken with or mixed into the brew) are now among the risks of those seeking mind-altering experiences.

“People need to do their homework before doing this,” said ethnobotanist Chris Kilham. “The most important thing is that when I say ‘drinking ayahuasca,’ I mean engaging in the ceremony with a talented shaman and not just swallowing the brew in somebody’s basement. Swallowing the brew is part—and only part—of the experience.”

Kilham knows whereof he speaks. Once called the “Indiana Jones of natural medicine,” by CNN, Kilham has spent more than four decades conducting research on traditional plant-based medicines through botanical expeditions worldwide. He often stays in local villages as a part of his research. While there, he looks to connect Western medical practices to the natural, homeopathic plant remedies that indigenous peoples have used for thousands of years.

Kilham recently returned from his 38th trip to the Amazon (where he contracted his second bout of malaria). On his latest expedition, he conducted research on the cultivation and cultural phenomenon of ayahuasca. For centuries, local shaman have mixed the vine with the leaf of another plant and used the resulting concoction to unlock the mind in spiritual ceremonies.

In present day Peru and Ecuador, this brew goes by ayahuasca, which comes from the Quechuan language (the indigenous tongue spoken in the Andean region of South America) and translates as “vine of the soul,” or “vine of the dead.” But in Colombia, the vine and the drink are more commonly referred to by the Tukano name of yagé or yajé.

“The odds of selecting these two plants from all the others is a multi-billion-to-one long shot,” Kilham noted. So how was the nearly impossible connection between them made? “The shamans will—soberly—tell you that the plants originally told the people.”

No matter how ayahuasca was first discovered, now that the secret is out, more and more people are telling each other about it—both raving and warning about its effects. In addition to word-of-mouth buzz, there is also a r/Ayahuasca subreddit that features nearly 13,000 different user experiences. And last year, none other than A-list star Leonardo DiCaprio executive-produced a Netflix documentary, The Last Shaman, that focused on a young college student suffering from incurable depression who had given himself 12 months in the Amazon rainforest to see if Ayahuasca could help his condition.

This isn’t as far fetched as it may sound. Ayahuasca triggers primitive parts of the brain that uncover vivid emotional memories, an addiction researcher told The Guardian. But earlier this year, the first randomized, placebo-controlled clinical study of ayahuasca suggested that the drug could also be used to treat severe depression.

Whether it’s thrill-seekers on a quest for their next big high, or the desperate in search of a cure for mental maladies, all of them are contributing to a booming ayahuasca tourism business.

Typically, the price of one- to two-week ayahuasca retreats range from $1,700-$3,500. More popular destinations, like Peru’s “Temple of the Way of Light,” will charge a premium for accommodations that include amenities such as laundry service, yoga classes, purifying floral baths, guided dieting, and porters to carry your luggage in and out of the Temple from the boat.

All this traffic and attention doesn’t come without its downsides, however. Retreat centers where shaman serve up ayahuasca are now cropping up all across the Amazon. And, increasingly, Westerners aren’t taking the psychedelic drug in the same way that indigenous tribes traditionally have. According to Kilham, the native people in the Amazon might drink it a handful of times over the course of seven weeks. But to accommodate the interest of tourists who have come a very long way—and are likely only visiting for a brief amount of time—Kilham has seen the traditional ayahuasca dosing regimen thrown out and replaced with a kind of binge session to accommodate foreigners. Some week-long retreats catering to tourists might serve the brew as many as four or five times, he noted.

As shamans figure out how to best work with tourist interests, Kilham has seen a blending of cultures take place over the past 11 years he’s experimented with the drug, met with more than 70 shamans, and participated in more than 130 ayahuasca ceremonies. In preparation for any ayahuasca trip, he strongly recommends doing due diligence on retreat centers by talking with previous visitors and taking basic safety measures to validate that all shaman are trained and qualified. All his research has led Kilham to write The Ayahuasca Test Pilot Handbook, a best-practices guide for finding safe and legitimate shaman-led ayahuasca experiences.

Safety has become an increasing concern in the ayahuasca community. At the end of August, The Guardian reported that a 19-year-old British backpacker died after taking a fatal dose of yagé and scopolamine in a ceremony in the Colombian jungle four years ago. Last year, a 24-year-old New Zealand native went into cardiac arrest and died after taking ayahuasca at a retreat in Iquitos, Peru. His was the fifth ayahuasca-related fatality in that region of Peru since 2015. And sometimes it’s not just the drug itself that brings risks. This past April, a tourist was lynched by a mob in Peru after being accused of killing a revered shaman during a ayahuasca ceremony.

But in an age where self-discovery efforts abound and meditation and mindfulness efforts have grown almost banal, using Ayahuasca has become a sort of trendy subculture: the next new high.

Ayahuasca’s growing appeal has also penetrated one of the country’s most well-known counter-cultural, psychedelic-friendly events: Burning Man. One recent Burning Man attendee, a 35-year-old man from London I’ll call Brit (not his real name), said he recently traveled to Peru on an ayahuasca retreat with intentions to “unblock something” hindering growth in his life. He’d previously experimented with DMT (dimethyltryptamine), a major psychoactive substance found in ayahuasca, which is categorized as an illegal psychedelic substance in both the U.S. and the U.K.

While Brit likens other psychedelics to “picking up a comic book,” he said his experience with ayahuasca was “like walking into an incredible, 4-D rendition of a realistic computer game.” Its effects were so powerful, Brit claimed, that he was able to talk with his deceased parents while under its influence. “Ayahuasca showed me that we’re all connected. I could feel everybody that I knew and loved.”

However, Brit acknowledged that he had been apprehensive about going to Peru on an ayahuasca quest after hearing about others’ experiences. So, to prepare his mind in the weeks leading up to his trip, he abstained from Internet and television, and, while at the retreat, journaled his thoughts about his experiences. And to moderate his intake, Brit chose to drink ayahuasca just two times during his nine-day Iquitos retreat, which offered four ceremonies.

This kind of preparation is a good idea, according to Kilham. He recommends plotting a kind of a mental and emotional roadmap prior to embarking on any ayahuasca experience—much like planning a route and destination for any real-world trip. Preemptively organizing one’s thoughts through writing or meditation can help the mind once it falls under the drug’s influence, he said. “Setting that intent does set direction.”

Another key point for any prospective ayahuasca tourist to understand: the detox from the drug makes a hangover look inviting. Known by some natives as “La Purga,” the aftereffects of ayahuasca include severe vomiting, diarrhea, crying, or laughing. According to Kilham, this often painful purging isn’t merely an unfortunate side-effect, but a key, cathartic aspect of the overall experience.

“You purge mentally, emotionally, physically, and lots of different ways,” Kilham explained. “You might be sitting there feeling perfectly fine, but tears are streaming down your face. And if you look into the biochemistry of tears, you’ll discover that they are extremely rich in stress hormones. …It’s all part of not just cleansing the way we tend to think of it, but a deeper and more profound mental, emotional physical cleansing.”

Still, Kilham emphasized that there is only so much preparation one can do for the powerful emotional flashbacks and intense physical reactions that are induced once you are immersed in the world of ayahuasca.

“You can’t know ayahuasca until you drink it. You can’t know what that experience is going to like.” Kilham said. “It might be easy, and it might be scary.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.