It starts with the slow crawl out of the house, the dull hum of the car AC and the asphalt infinity of I-95. From New York to Massachusetts, you barrel over cracks in the concrete and watch as dots on the horizon become gas stations and Dunkin’ Donuts. When you make a pit stop, you should drink a frozen lemonade, then a coffee and then another, then get back on the road and plan not to stop again. Civilization is billboards, arenas and towns. What’s beyond is just wilderness and sea — you’ll know it when you pass through Portsmouth and watch the sun rise over midcoast Maine.

In a 2004 lament for Gourmet magazine, David Foster Wallace estimated that midcoast ended somewhere around Belfast, on the north shore of Maine’s Penobscot Bay. Though he couldn’t exactly pinpoint the boundaries of the region, he knew what lay at the center: “the nerve stem of Maine’s lobster industry,” lined with worn wharfs, red-brick downtowns and fishermen killing time. To Wallace, Belfast was the last bastion of that culture, before Route 1 disappeared beneath Acadia traffic, and lobstermen became park rangers.

Belfast is a small town with a soul in the sea. With a population barely scraping 7,000, it’s a sort of New England Mayberry, where all faces are familiar and family comes first (though in this version of Andy Griffith, Barney smokes pot). The dual focus on aquatic life and community means that young Belfasters are encouraged to question how business affects their home. Most times, that means getting on the water and finding out first-hand.

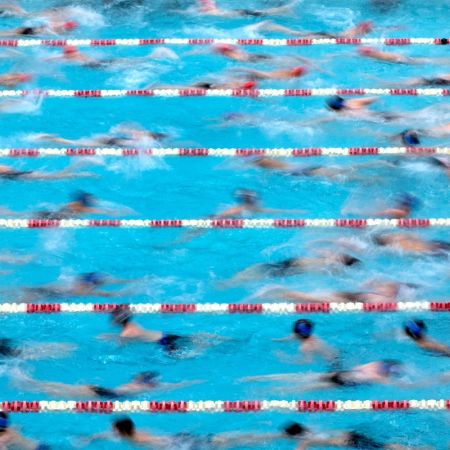

The belle of the midcoast ball is the Maine lobster, perhaps the best-tasting, highest-quality shellfish catch on the planet. Like all crustaceans, lobsters are an ectothermic species. That means that their body processes — their immune and respiratory systems; the times at which they molt and reproduce — are determined by water temperature. Since the early ‘80s, climate change has spurred a lobster supernova in Penobscot Bay, as unbearable southern heat has shepherded the crustaceans north. Today, midcoast Maine stands as one of the most lucrative seafood hotspots in the world. But soon, that ephemeral moment will come to a close. For thousands of East Coast fishermen, climate change is a waiting electric chair.

“A lot of lobstermen are trying to diversify their job, because as the water warms, the lobsters are moving out,” explains Alicia Gaiero. “So they need another form of income, whether it’s oysters or kelp.” Gaiero is a Belfast native who entered the seafood industry as a college student. Because of climate change, she explains, we’re seeing “the great expansion of small-scale aquaculture.”

In the Gulf of Maine, one of the fastest-warming regions in the ocean, aquaculture is quickly becoming a trademark art. While fishing is volatile and conditions-dependent, aquaculture demands fewer inputs, less space and limited emissions. It’s the monitored cultivation of fish, crustaceans and plants; it’s also Maine’s answer to the climate crisis, and a potential future for the stumbling seafood industry.

“I got involved in aquaculture when a large, land-based salmon farm proposed coming to Belfast,” Gaiero tells me. “I was curious about what that meant for our community.” While she is just 26, Gaiero helms Nauti Sisters Sea Farm (NSSF), an aquafarm she founded in early 2020.

Six years ago, she accepted a position with the New England Ocean Cluster, a sustainability firm aimed at directing “marine resources towards responsible practices.” In 2019, balancing school against the sea, she moved to Portland where she interned with the Maine Oyster Company. “I grew up loving seafood, but I’d never actually had an oyster,” she explains. “[I had my first] on this beautiful fall, romantic day. It’s flat, calm, full of foliage. It’s like a warm day in October. And I was like, ‘This is amazing.’ At that point I was coming to understand that I wanted to work in aquaculture.”

Later that year, Gaiero began to toy with the idea of opening her own oyster farm, but it was still an abstraction — a faraway dream that she figured came after money, experience and grad school. However, in February 2020, she set up shop on Littlejohn Island, a stone’s throw from the rocky coast of Yarmouth. “I call it the graduate school of life,” she says. “And I’m proud that I took that risk.”

Nauti Sisters Sea Farm is named triply for Alicia’s sisters, her nautical obsession and the disobedient streak which pulled her out of school and into the water. Despite its family ties, it started as a one-woman operation. “I really didn’t have a lot of idea what I was doing,” she explains. “I learned how to haul a trailer, and then I got support from other farmers.”

This Coastal Maine Town Is Preserved in Time (in the Best Way Possible)

Where to eat, stay and play in YorkAs the business blossomed on Maine’s southern coast, the other Gaiero sisters were doing as Belfasters do. Amy, now 24, was in pursuit of a degree in sustainability. Chelsea, now 19, was cycling between positions in the seafood industry, and according to the NSSF website, she “may have the most diverse experience in Maine’s working waterfront.” That includes time spent “on the stern of a lobster boat [and] as team member for a mussel farm.” Alicia notes that as Nauti Sisters expanded, its name proved prescient. “In the past two years, everyone has gotten on board,” she says. These days, Amy is employed as the farm’s manager, while Chelsea helps out between semesters of college. Earlier this year, both received their captain’s licenses from the U.S. Coast Guard.

As the farm developed, Alicia adapted, then swapped locations. While Belfast’s coast is in the northern reaches of Penobscot Bay, Yarmouth’s is in the heart of Casco Bay, about 75 miles southwest. While that doesn’t sound like much, it can make a tremendous difference in the delicate world of shellfish. “Where our farm is, it takes about 18 months to two-and-a-half years for our oysters to reach market size,” Gaiero explains. “Up on Islesboro, just across from Belfast, the farms take a minimum of two-and-a-half to three years for about the same return.”

The Eastern Oyster, the premier species of oyster in the American Northeast, matures faster in warmer temperatures, particularly brackish bay water close to 60 degrees. Colder water, like the mid-50s of Penobscot Bay, means longer life cycles and smaller yields. But the greater threat is increased heat: temperatures which climb too high can limit oceanic oxygen and inhibit oyster growth permanently.

For Gaiero, for now, Maine’s warming gulf is a boon — oysters are a reactionary species that hibernate as temperatures drop, so rising heat means a shorter rest and a longer period of feeding and growth. But as climate change intensifies, she’s staying wary. “The oyster farmers around me who’ve collected data are seeing documentable warming temperatures in our waters, sometimes by our farm,” she says. “The coast of Maine is not supposed to feel like bath water.”

The Gaiero sisters are young women in a field dominated by “salty old dogs.” That truth has forced questions about personal and brand identity, and answers which have propelled Alicia to unprecedented success in an oversaturated market. While the average farmer is operations-minded, she maintains a social focus.

“I often joke that other farmers didn’t used to like me because I got a lot more media,” Alicia says. She credits her memorable brand, a cute merch line and a stellar online presence. “Look, my tool is that I’m good at Instagram and your tool is that you’re actually good at farming,” she laughs.

The Gaieros are also story-focused: “People really have attached to the idea of three sisters in Maine growing oysters and working really hard for shit.” That’s not to say Alicia doesn’t take pride in the quality of her bivalves. “We’ve earned our place on the water over the past several years,” she grins.

If the Belfast ethos is predicated on community and sustainability, the Nauti Sisters are inextricable from their roots. “The least important thing to me is the oysters,” Gaiero expounds. “It’s the intrinsic value of working on the water most of the year that’s really incredible and challenging and exciting. Then there’s this other component, where I get to work with my sisters and a number of incredible young women.”

Alicia looks at Chelsea, then smiles knowingly. “The oysters are just the byproduct of the things we get out of them.”

Join America's Fastest Growing Spirits Newsletter THE SPILL. Unlock all the reviews, recipes and revelry — and get 15% off award-winning La Tierra de Acre Mezcal.