The Global Fashion Capital is flashing its not-so-luxurious underbelly. In a series of probes and raids earlier this year, Italian authorities uncovered multiple fashion workshops in flagrant violation of national labor standards. Machinery surveyed during the raids had safety mechanisms removed in an effort to increase productivity, an issue compounded by the fact that most employees lived on-site. Among the dozens working in the implicated shops were a handful who were either illegal immigrants or paid off the register. While shop conditions were dismal and wages ran south of €3/hr ($3.22 USD), the merchandise workers produced was luxe, and sold in Dior and Armani stores. Though those companies haven’t been implicated in the ongoing investigation, they have been chastised in court rulings for “failing to adequately oversee their supply chains,” raising broader concerns about the negligence of luxury fashion houses.

“While other sectors have moved manufacturing to China and other low-wage countries, many luxury brands kept production closer to home,” noted the Wall Street Journal. In an industry in which legitimacy is crucial, the “Made in Italy” tag is a coveted one, which manufacturers are eager to maintain at any cost. The suppliers’ solution was simply to bring those low-wage employees into Milan, undercutting law and common ethics in a cheap trick to keep costs low and prices high.

Of particular interest in the weeks following the raid has been a bag said to epitomize Armani’s supply chain process. These bags “got sold to Armani suppliers for 93 euros, re-sold to Armani for 250 euros, and cost about 1,800 euros in shop,” wrote Reuters in April. While the corporation has emphasized their attempts to “minimize abuses in the supply chain” and intent to maintain “the utmost transparency” with Italian authorities, figures like those should have raised red flags.

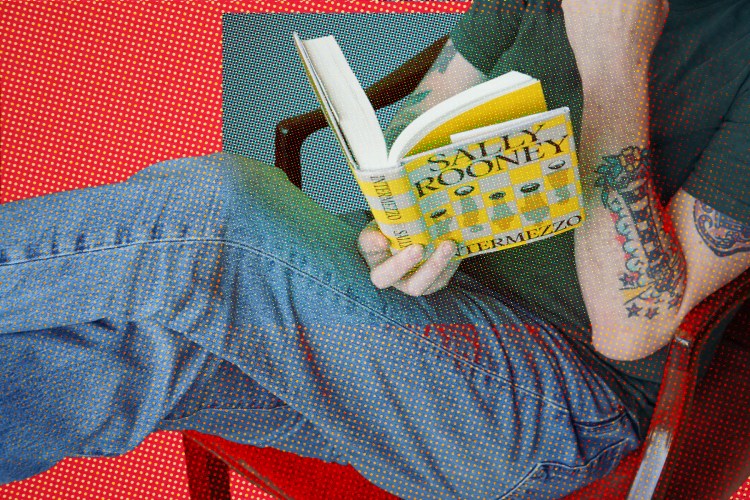

Jake Gyllenhaal and “SNL” Took On the Ethics of Fast Fashion

One part satire, one part physical comedy“You’d think ultra-low prices would ring alarm bells,” Fabio Roia, the president of Milan’s court system, told Reuters last month. “If someone offered me a Rolex watch costing 50 euros, I’d be wondering where it comes from.” Though Armani and Dior have escaped prosecution at present, Roia has held their negligence in the limelight. “We’ve noticed companies don’t invest enough in their control systems,” he explained. “They simply seize the chance to maximize profit.”

Worth noting is Armani’s role as a hometown brand, both founded and headquartered in Milan. In a passion piece last January, Lampoon called Giorgio Armani a man dedicated to “civil commitment.” Now, as Giorgio rapidly approaches $12 billion in net worth, it’s being unveiled that sweatshops are churning out products stamped with his name just miles from his backyard. An analysis of electricity reports from the shops revealed workdays began at dawn, ran until the late evening and did not pause for weekends or holidays. Then, last week, Armani celebrated the unveiling of its new “Freedom in Nature” collection.

Though Dior and Armani are not under direct investigation, they have been placed under “court-ruled administration,” a status in which appointed commissioners take on the role of overseers within a company and report their findings directly to the court.

As Milan’s court system calls for increased checks on labor law violations, the luxury industry is facing a score of other issues. Among them is a supply nightmare, as consumer wages plummet and fashion house execs refuse to lower prices. Consumer Edge reported that direct-to-consumer luxury spending fell by 7% last year, an aching downturn from a 15% increase in 2022.

Earlier this year, the EU voted to ban the “incineration of fashion waste,” as the Wall Street Journal reported, a once-preferred solution to the over-stock problem. In the mind of a fashion-house executive, trashing branded items would result in a tarnished image, while keeping them — and certainly discounting them — would spell humiliation. Thus, the sector’s top dogs find themselves at yet another crossroads. Certain brands, including Burberry, have taken to “buying back unsold products from department stores,” a tactic which merely diverts the waste issue to their own warehouses.

Unofficial resellers — once the bane of the luxury industry — have reported receiving direct calls from brands, offering to sell them merchandise without the usual retailer acting as middleman. It’s a deal-with-the-devil situation for fashion houses, who have long sought to stomp out the profiteers, but as the luxury market hits bumpy roads, it’s a viable temporary solution.

Buried under the weight of unsold goods, luxury executives are now forced to look inward and consider how many faulty stitches it will take before the industry comes entirely unwound.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.