The name Michael Mauldin might not be on the tip of your tongue when you think of Black music icons, but you do know many of the musical artists whose careers he helped forge and nurture as the President of Columbia Records Black Music division a few decades ago.

Ever heard of Nas? The Fugees? How about Alica Keys or Beyoncé? Yeah, I thought so.

These days, Mauldin has taken up a new cause: to better educate music listeners about the history of Black music through the efforts of the Black American Music Association. The organization, which Mauldin co-founded, develops various programs to carry out this mission, and its latest is a black-tie affair that happened June 2 at the Bank of America Plaza in Downtown Atlanta, Georgia. Dubbed The ICE Medal of Honor event, the Black American Music Association is set to honor “legends, creative visionaries, and trailblazers within Black American music, who have captivated audiences worldwide and left an everlasting impact on the cultural landscape,” per a press release.

Ahead of the festivities, InsideHook spoke to Mauldin, the inaugural ceremony’s executive producer, about the importance of more widespread education about Black music’s legacy, his humble beginnings in the music business and the state of Black music today.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

InsideHook: What is the goal of the Black American Music Association?

Michael Mauldin: To preserve, protect and promote the legacy and the future of authentic Black American music, its community, its culture and its creatives. We want to make sure that people understand Black American music, how it started and where it came from. When you talk about Black music, it’s not completely about race or creed or the color of your skin, it’s about an art form.

Why do you feel like that all is so vital to the broader culture?

We started in 2015 because we noticed that when people spoke about hip hop and some of the other genres of music that fit within the category, they failed to realize it was all part of an art form that was created and put into play in a solid way about a hundred years ago. So we want to educate new listeners, but also a lot of established people in the music industry, and everyone in between, about where Black American music comes from and where it’s going.

A lot of Black musical groups and artists got started in churches, but also in schools, and we started to notice that the powers that be were devoting less money to music programs in schools. We saw a void that needed to be filled. So we’ve partnered with a number of Historically Black Colleges and Universities for education programming. We also provide mentorship to young artists.

We’re trying to get to everyone between the ages of 10 and 21, which means we have to get into the high schools and middle schools, too, which we’re starting to do. We have a Walk of Fame outside Mercedes Benz stadium here in Atlanta, where we’re based. Our last induction ceremony was in October, and we capitalized on the 50th anniversary of hip hop, honoring artists like Lil Wayne and Queen Latifah. But the festivities started with a performance from a high school marching band because we wanted to show the connection.

What is the benefit of such knowledge to music lovers or just anyone in our society?

There’s got to be an opportunity to get our kids back into entertainment that is not always so profane or always so left of center that it can’t be embraced by everybody. That’s important to us. We’re trying to figure out how to position our industry, as well as our community and our culture, in a place where we can create kind of a handoff, and be able to say, “Hey, just dig a little bit deeper.” And I really believe that as we do that, as kids particularly get to understand the depths of where music can go — by using Black American music as research, by going back to Motown or to the 1920s, what was going on in the Harlem Renaissance era, and identify with some of that — I think that we will find that our music becomes more creative. Right now, we’re in kind of a stale space with music. There’s hip hop that’s ranking, but we’re not in a place right now where we’re capitalizing on music the way we should be.

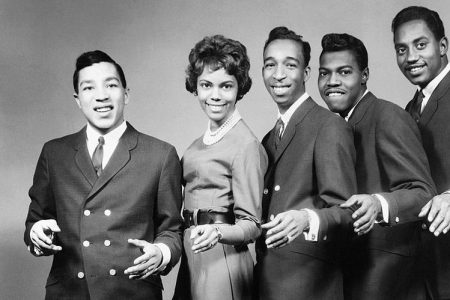

The "First Lady of Motown" Looks Back on the Legendary Label's Early Days

Claudette Robinson was the first woman to be signed by the legendary Detroit labelTell me about the ICE Medal of Honor. What can we expect from the upcoming ceremony?

“ICE” stands for “the Imperial Crown of Excellence.” We want to pay homage to a lot of those artists from yesteryear that didn’t get their due, across a series of honors.

For example, the Global Creative Impact Award is going to Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, a duo of songwriters and record producers. One of the themes of the ceremony this year is “love affair” — it’s a love affair of Black music, community and culture. We feel that Jimmy and Terry represent that as well as anybody.

They have an amazing story. They got fired together by Prince from his tour’s opening act, the Time. Not to say they wouldn’t be working, but if they had not gotten kicked out of the Time we may not have gotten the music that we did, when we got it from them. They produced the S.O.S. Band at that point and then later produced Janet Jackson, and went on to do many more things in music.

Not to knock any of these organizations, but when you see the Grammys, the American Music Awards, the Billboard Awards, or even the Country Music Awards, it’s always about what’s happening right now. I get the importance of that, but there are so many artists that are deserving of flowers and they get passed over.

When I was at Columbia Records, there was an artist by the name of Nancy Wilson. She was known to most as a jazz artist, but for me, she was more a modern interpreter of the art form called jazz. But for the longest time at Columbia, they almost had her sitting over on the side, and she was really a jewel. She was someone that we should have been lifting up, but there was no mode of operation inside of Columbia Records to give her a platform. There was no educational piece. That got me wanting to really tell stories, and make sure that people understood where a lot of this music comes from.

But we also honor well-known artists as well. We have the Michael Jackson Icon Award that we’re establishing. We also have an Ella Fitzgerald Gold Standard Award because Ella Fitzgerald was the gold standard as a vocalist. She also had incredible drive and determination. Awards like that give us ways to educate, as well as honor the artist.

And these honors are not just about the music. They’re also about what those individuals did for the community and culture, what they did to help position not only the art that they were making, but standout political messages as well. We have a Ray Charles/Harry Belafonte Patron of Arts Award. Harry Belafonte had music that crossed over in so many ways, but he also had a political voice. He was on the front lines with Martin Luther King and made a difference for the community and culture of Black Americans, so we’re casting a spotlight on that aspect of his life as well.

Tell me about how you got started in music.

I’m from a place in western North Carolina called Murphy that literally was a one-stoplight town. Everyone there knew music was my thing. I was in a high school group that was one of the first integrated bands in the area. I was the lead singer, and I went on to play drums and do a bunch of other stuff. But I had a van that we used to get around and transport equipment. We called it the Ghetto Super Van; it had that written on the side of the van and everything.

A friend of mine was in the group Brick. He called me and said that they’d just done a gig and outside north Atlanta the car with their equipment in it broke down. He asked me to drive down with the van and help get them to the gig in the city. I said, “No problem.” I showed up with the van and it held way more equipment in it than one of their cars did. The leader of the group, the bass player Ray Ransom, said, “Man, Michael, we have another gig tomorrow in Savannah, Georgia. Do you wanna take the gear over to Savannah, too? We’ll buy the gas and buy you a hamburger and give you 15 dollars.” I’m like, “Of course!”

When we got to Savannah, it was a show with Hot Chocolate and a bunch of other groups from back in the day. When Brick is on stage setting up, I jumped in to help because I was very familiar with the equipment and the instruments. I was creating a job for myself, not really knowing that’s what I was doing. Before you know it, they have a song that blows up, “Dazz,” and they didn’t need my van anymore. They brought in a 22-foot truck, and I became the truck driver. My role grew into stage manager; I started hiring crews and then I said, “OK, now I’m the ‘production manager.’”

I realized that producers were getting more money than the performers, and at the time there weren’t more than a few Black production managers. I formed my own company, MTM Roadworks, and it seemed like everybody wanted to work with me.

In the 1980s I produced the Fresh Festival, in New York, which tied me to hip hop in a major way. My son, Jermaine Dupri, was the opening act at one of the Fresh Festivals and then he caught on and propelled me deeper into the hip hop world.

Over the years things just kept developing; I started managing more artists and here I am today. God is good.

You’ve helped launch and nurture the careers of so many huge artists. When you’re around people like Beyoncé, Lauryn Hill, Alicia Keys or Nas, what is it about them that makes you think they’ve got the goods to be stars?

Honestly, man, their work ethic. Beyoncé, even at 14 or 15 years old, let me tell you, she was a worker. She came to that from her family. I just always looked at that and I wish I could go back and grab that and bring it forward for other artists. But they also all represented something to me that wasn’t happening at that time, and it was very important that someone like me took what they were doing and ran with it.

The Fugees were already signed to Columbia before I got there, but I put their second album, The Score, on pause because I wanted to make sure we got it right. It was an opportunity to have Black music recognized globally like it had never been recognized before. And that actually happened with The Score; it was No. 1 in damn near every country across the world. There was always a kind of drive to do that with these artists.

What do you think of Black music today? What are you hearing? Is it maturing in a way that will keep it sustainable?

That’s a big question. I feel like it’s a little watered down, and I’ll tell you why. It’s part of what I’m telling you: I don’t think there’s enough research behind it. Hip hop is so influential, and that’s great, but now you’re finding everything — whether it’s R&B or whatever else — has to have rap in it. And if you do, it’s got to be profane or else people don’t want to listen to it. It’s all contrived, in my mind.

However, you also have Afrobeat music, and the Grammys has an Afrobeat category now. There are some great records that have come out of Afrobeat that kind of broaden the reach of Black music through different rhythms and different ways that people can interpret it.

I also love some of the things happening with country music because it’s pushing the envelope and making Black artists reconsider what their next record will be. I just had a conversation with a very prominent R&B artist last week about the fact that they were thinking about doing a country song. And I looked at them sideways, but then they were like, “Well, everybody’s jumping in and, I don’t want to just do it, but that’s always been my thing.” And I think what attracts Black artists to country is the soul of it all.

But I do feel like we need an injection of newness and creativity in Black music. And I think part of it is just, again, like I said, people coming together in a more educational setting to understand the boundaries a little bit better.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.