One hundred and sixty-five miles south of Miami, beyond the lower reaches of the Everglades, and at the end of a narrow finger of land veering westward into the Straits of Florida, lies the 4.2-square mile island of Key West.

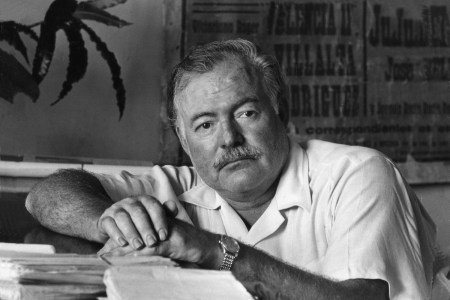

The Seminole and Calusa Indians lived here first, and Spanish settlers officially named it “Cayo Hueso” (Bone Island) in 1822. Since then, it has been home to cigar makers, shipbuilders, smugglers and pirates. Many of these pirates have been of the literary variety: Truman Capote lived and worked here. John Do Passos. Tennessee Williams. As did, famously, the great white whale of American literature, Ernest Hemingway, who once called the island the “St. Tropez of the poor.”

“The moon was up now and the trees were dark against it, and he passed the frame houses with their narrow yards, light coming from the shuttered windows; the unpaved alleys, with their double row of houses; Conch town…” Hemingway writes, describing the poverty and vice of Key West, where the locals, the Conches, live away from the tourist areas in his tale of Depression-era smuggling, To Have And Have Not.

Today, Key West is reachable by car over the 113-mile Overseas Highway; the island is surrounded by the same azure bath-temperature waters, while descendants of the same chickens roam the streets alongside middle-aged tourists instead of rumrunners. Home to the Southernmost Point of the Continental U.S.A. and just 90 miles from Cuba, for Americans, Key West is as far as you can travel without stepping into another world entirely.

The Hemingway Guide to Miami and Key West

Dining, fishing, drinking and cavorting in Papa’s footstepsAs a Brit, visiting Key West on the 125th anniversary of Hemingway’s birth was something of a pilgrimage. Years earlier I’d travelled to Havana, stood by the bronze statue of “Papa” in El Floridita and drank the double daiquiris with no sugar that the painter Thomas Hudson self-prescribes for his melancholy in Hemingway’s novel Islands In The Stream. Hemingway has undergone a cultural reappraisal in recent years, least of all for his attitudes towards women and masculinity. Considered boorish in his lifetime, today we think of certain aspects of his outlook as practically prehistoric. Still, his prose remains undeniable. Re-reading Hem on this trip felt like a course correction, a reminder to make my own fiction and journalism more direct, more appreciative of the dry nuances of human speech and the way simple descriptions can capture beauty.

Hemingway first came to Key West in 1928 with his second wife Pauline Pfeiffer. Things didn’t immediately go to plan. A new Ford Roadster, a wedding present from Pauline’s uncle, had been delayed in transit. By way of apology, the Ford dealership offered the couple an apartment above its showroom on the island. By this time, The Sun Also Rises was in its eighth printing, and Hemingway the Great Writer was firmly in the ascent.

“No amount of analysis can convey the quality of The Sun Also Rises. It is a truly gripping story, told in a lean, hard, athletic narrative prose that puts more literary English to shame,” ran a New York Times review at the time.

During the three weeks the couple spent waiting for their car, Hemingway finished the first draft of his next novel, A Farewell To Arms. In 1931, he and Pauline decided to make the move permanent, settling in a dilapidated Spanish Colonial house at 1301 Whitehead Street which Pauline renovated while Hemingway worked.

Today, the Hemingway Home is a museum, offering guided tours led by your very own late-Hemingway lookalike. The leafy gardens are home to over 40 six-toed cats, descendants of Snow White, a cat that traveled down from Massachusetts with a ship’s captain, who gifted Hemingway a kitten. Both cat and captain were “well regarded along the waterfront,” a sign explains.

Our guide relays that during Hurricane Irma in 2017, all 40-plus cats were moved into the house, puncturing inflatable airbeds with their claws and leaving their hosts to sleep on the hard wooden floors as the storm raged outside.

Inside, the Hemingway Home is surprisingly modest. Furniture is of the period, including bathroom tiles and light fixtures brought over from Paris. The walls display posters, letters, photographs summarizing Hemingway’s career and family life; all three of his children lived in the house.

In the grounds is Key West’s first and only in-ground swimming pool, constructed by Pauline at a cost of $20,000 while Hemingway was off covering the Spanish Civil War with Martha Gellhorn, whom he’d met in Key West a year earlier, and who would become his third wife in 1940.

When Hemingway returned, he reportedly asked Pauline what the hell had happened to his boxing ring before flinging a penny into the still-wet concrete, where it still sits today. “Pauline, you’ve spent all but my last penny, so you might as well have that!” the story goes. When Hemingway relocated to Cuba in 1939, Pauline stayed behind, living in the house until her death in 1951.

Our tour group is mostly older. Patti, a grey-haired woman in gardening attire, is from Connecticut. “It’s marvelous to see where he really lived,” she says. “There’s no one quite like him.” Her husband nods silently. “We like all of his writing.”

Our guide claims 70 percent of Hemingway’s work was finished here in a converted writing studio on the second floor of the carriage house. Each morning, Hemingway would reach his studio via a second-story walkway and write in solitude until noon. He often wrote standing up, accompanied by at least one of his cats.

The studio — preserved exactly as it was, except for the addition of an iron mesh to keep visitors out — is a small, square room full of light. A typewriter sits on a round table beside a chaise lounge. Bookshelves line the walls. Above them, hunting mementos in the form of glittering fish, and an antelope bust.

“The more I’m let alone and not worried the better I can function,” Hemingway once wrote.

It was in this room that he wrote, among other titles, his non-fiction work Green Hills of Africa (1935), the short story “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” his bullfighting epic Death In The Afternoon (1932).

Short of a Spanish Colonial house of our own, we stayed at the nearby Casa Marina, an airy and spacious hotel that provides welcome shelter from the blinding heat of Key West’s streets. If reading To Have And Have Not on a private beach felt at odds with the book’s message, the hotel’s history felt of a piece with the Key West Hemingway would have known.

Opened on New Year’s Eve, 1920, the hotel was conceived by American railroad tycoon Henry Flagler and designed by the same architects responsible for the New York Public Library. President Warren G. Harding stayed there, as did Gregory Peck, and Rita Hayworth, as well as Jimmy Hoffa. Through the haze of an Old Fashioned in the hotel’s The Canary Room, it isn’t difficult to imagine Hem rubbing shoulders and trading belligerent barbs with such a crowd.

“You aren’t a true Key West resident until you’ve been hooked by Hemingway,” Katie Monts, our bartender tells us. “You can feel his legacy everywhere. The Old Man and the Sea is a personal favorite.”

To celebrate Hemingway’s birthday, the hotel is offering oceanside book club chats, fishing excursions and rum tastings with the local Papa’s Pilar Rum Distillery, named after Hemingway’s boat, Pilar. Hanging around the Keys, Hemingway fell in with the local big game fishermen, discovering a lifelong passion he would write about time and again.

“You did not kill the fish only to keep alive and to sell for food, he thought. You killed him for pride and because you are a fisherman. You loved him when he was alive and you loved him after. If you love him, it is not a sin to kill him. Or is it more?” Hemingway writes in the Nobel Prize-winning The Old Man And The Sea.

Unfortunately, sickness saw us land-locked. Neither myself or my partner have the bloodlust — or cash — required to go in search of marlin, but there are plentiful glass-bottomed boat and snorkel trips available, which felt close enough.

You don’t have to take to the seas to appreciate Hemingway’s legacy. Independent book stores Books & Books and Island Books carry a full range of Hemingway and Hemingway-adjacent work, as well as work by local authors. Meanwhile, on the main drag of Duvall Street, everything from Hemingway key rings to Hemingway shirts and Hemingway-themed cocktails are available.

Sloppy Joe’s, located at the corner of Duval and Green since 1937, is a good place to avoid the heat and the more garish tourist bait. Opened by Joe Russell, a Conch and a Prohibition-era rumrunner who worked as Hemingway’s boat pilot, the original bar — then located at 428 Greene Street — was a freewheeling fisherman’s bar that appealed to Hemingway immediately. It was Hemingway that encouraged the name change, and he later modeled Freddy, the owner of Freddy’s bar in the novel To Have and Have Not, on Russell.

While the bar was being relocated, Hemingway stopped by and found one of the old porcelain urinals discarded in the street. He lugged it home to his garden at Whitehead Street where it sits today as a drinking trough for the cats.

The modern Sloppy Joe’s is a more commercial night out, with a menu that serves almost anything you want — although, it helps if it’s fried. It’s also home to the annual Hemingway look-alike contest, which sees over 150 white-bearded men compete for the honor of being crowned “Papa.”

David Douglas is the 2009 winner and president of the Hemingway Look-Alike Society. At 70, he’s a big, burly guy resembling Hemingway in his later, Idaho days. His enthusiasm for Hemingway is yet to wane, as he tells me over email.

“A friend visited me in Montana after going to Key West on vacation. He brought back a life-size poster of Ernest Hemingway and held it next to me, saying I had the look. After about six months I decided to enter the contest on a dare,” Douglas explains.

“The contest creates a lot of new friendship, and camaraderie that last a lifetime,” Douglas continues. “As part of the contest we support local charities and sponsor a baseball team in Cuba that Hemingway first started.”

Like most guys his age, Douglas first read Hemingway in school. The Old Man And The Sea is also his favorite. “Key West has a great admiration for Hemingway and the life he lived during his years here,” he says. “You can feel his presence in real time, with the statue in Mallory Square, and at Captain Tony’s bar. We hold a celebration [of his work] each year at a different location.”

If Key West is a place playing perpetual homage, there might be an unintended element of irony to the festivities. In Hemingway’s eyes, perhaps, a Brit tourist such as myself had no business being there at all.

“My family’s going to eat as long as anybody eats. What they’re trying to do is starve you Conchs out of here so they can burn down the shacks and put up apartments and make this a tourist town,” he writes in To Have And Have Not. “That’s what I hear. I hear they’re buying up lots, and then after the poor people are starved out and gone somewhere else to starve some more they’re going to come in and make it into a beauty spot for tourists.”

Or, perhaps, 125 years after his birth, Hemingway’s outsized ego would feast on the attention and the fact that he is still celebrated as one of the greatest writers who ever lived.

Either way, after three days we got back in the car and set off, heading northward to the next spot, carrying a bag of his books with us.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.