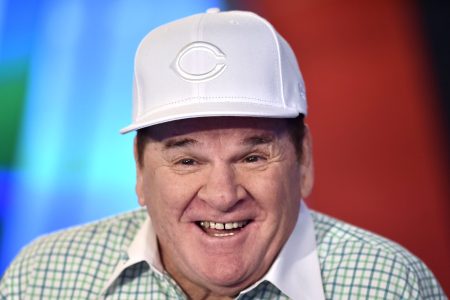

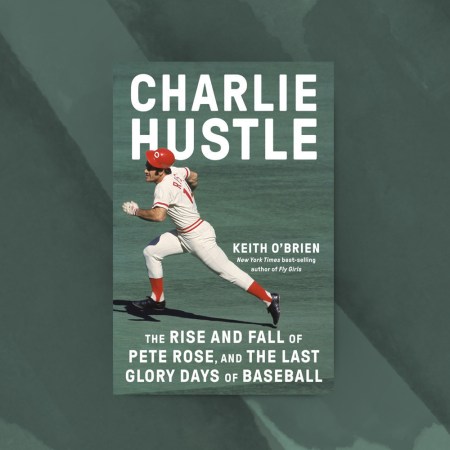

Although Shohei Ohtani may eventually give Pete Rose a run for his money, there is no star athlete who is more associated with the fallout of betting on sports than the 82-year-old Hit King. New York Times bestselling author Keith O’Brien grew up in Cincinnati before Rose’s brutal fall from grace and witnessed his shocking downfall first-hand. In his new book Charlie Hustle: The Rise and Fall of Pete Rose, and the Last Glory Days of Baseball, O’Brien, who met with Rose and spoke with him on the record for 27 hours, documents the legacy of the man who is arguably the most controversial figure in the history of Major League Baseball.

The following excerpt from Charlie Hustle details the night of September 11, 1985, when Rose collected career hit No. 4,192 at Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati to break Ty Cobb’s long-standing record for career hits.

The standing ovation lasted for seven minutes, long enough that the umpires stopped the game and the pitcher sat down on the mound. Seemingly bored, and with nothing to do, the sad hurler for the visiting San Diego Padres crossed his arms and rested them on his knees, while the subject of the endless applause, the Cincinnati Reds player standing on first base, finally broke down. He finally cracked.

Pete Rose began to cry.

For more than two decades, baseball fans had come to expect raw emotion from Pete. It was part of both his public persona and his internal character. He sprinted out walks, slid headfirst into bases, shouted at pitchers to intimidate them, knocked over catchers at home plate, and once broke a man’s shoulder in a meaningless game as he tried to score the winning run. But this — crying — was new for fans. And so, when the crowd at Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati saw him bow his head, hide his eyes beneath his shiny red batting helmet, and wipe away his tears with his new white batting gloves, the people cheered even louder. They loved Pete even more on this warm night in September 1985 because he had done it. He was now the hit king.

With his latest single — a clean, low-looping line drive to left-center field off that pitcher for the Padres — Pete had compiled more hits than any other player in baseball history: 4,192. More than Cobb and Musial, more than Aaron and Mays. Seven hundred more hits than Yaz. Twelve hundred more hits than the Babe. Fifteen hundred more than Teddy Ballgame. Nearly double the total of Joltin’ Joe, the Yankee Clipper, and as many as Bench and Berra combined. Pete had joined the list of the Immortals, players known far and wide by a single name. Indeed, he had surpassed them, all of them, and he would never look back, in part because Pete isn’t built for self-reflection and in part because he would never have to reexamine this part of his story.

Decades later, his hit record still stands. In a country where twenty-five million children might swing a bat every spring — and some sixteen thousand men have done it at the highest level, coming to the plate in a major-league ballgame with the dream of slapping a double down the line — no one has ever come close to matching Pete Rose’s hit record, and they probably never will. It stands there like a monument to the man himself.

Yet on this night in 1985, the fans in Cincinnati loved him for a different reason. For the reason they had always loved him and for what they knew to be true. Pete Rose wasn’t special. He was almost ordinary. Arguably, the most ordinary extraordinary athlete in the history of American sports. Hardscrabble and gritty. Less talented than tough. A Rust Belt hero for a Rust Belt town. He was just like the fans, the people cheering him now on this night in September. He was white, working-class and midwestern.

‘‘And again the flashbulbs go off all over the ballpark,” the city’s radio play-by-play man cried from the press box over home plate. “Hit number 4,192.”

“It’s a slider inside,” the television color man added in the next booth over, as the network replayed the record-breaking hit in slow motion. ‘‘And Pete hits the ball probably like he’s done four thousand times — a line drive over shortstop. And right there he knows it’s a base hit. He knows that’s it. And he rounds the bag the way he always does: all out.”

“This is his game. It is his town and it is his moment,” still another broadcaster added. Then, in a preplanned advertising stunt that’s impossible to imagine today, the broadcaster stood up in the booth, turned toward the camera, hoisted a can of Budweiser, and toasted Pete on national television. “This Bud’s for Pete Rose — and baseball,” the announcer said. “Just breathe it in.”

On first base, in that moment, Pete exhaled and shook his head, acknowledged the crowd, looked up, and then looked down, and as his gaze settled on his customary black cleats, he would have seen them squarely planted on the infield dirt. Pete was safe at first, as usual.

But the world had changed in the twenty-five years that he had been playing professional baseball, and it was changing still, even as Pete stood there at Riverfront Stadium that night, awash in the praise and the flashbulbs. The game that Pete had loved as a boy was no longer an unpolished American pastime, populated by men who had learned to play by hitting bottle caps in the streets and who worked off-season jobs in the winter to survive. It had become a big business where even the worst players made three times more than the average American, the biggest stars earned ten times more than the president of the United States, and owners operated like modern-day railroad tycoons. In 1985, baseball was on the cusp of its first billion-dollar television deal with CBS, and viewers tuning in to watch this modern game saw a product that looked different in ways that thrilled some people and rattled others.

Baseball — a sport that had been almost exclusively white in the 1950s — was now much more diverse. Thirty percent of the league was now Latino or Black, and by 1985 the biggest stars were players of color: Darryl Strawberry, Doc Gooden, Ozzie Smith, Fernando Valenzuela, Rickey Henderson, Kirby Puckett, Dave Winfield, Tony Gwynn, and both Rookies of the Year in 1985 — Vince Coleman and Ozzie Guillen. No big-city columnist was going to publicly celebrate a star player for being white, as they had once celebrated Pete and others of his generation, and no reporter was going to protect Pete either, because the chummy beat writer was gone now, too.

These writers — always men and often friendly enough with the players to go out carousing with the team on the road — had been replaced by a new generation of sports reporters, raised on Woodward and Bernstein. And these scribes weren’t beholden to the athletes in any way. What they wanted was a story, and they had competition to get it. New networks like CNN and ESPN were going to be happy to document a star player’s missteps, foibles, flaws and errors, because scandal was good for ratings, and no scandal was going to be more captivating in the 1980s than Pete Rose’s.

It was almost as if he were standing in quicksand that night at Riverfront Stadium — only he was unaware of the world beyond him. Pete didn’t know it, but he was sinking.

In the next few years a shorter time frame than anyone ever could have imagined — the cheering stopped and the toasts did, too, as baseball officials and reporters did something they had declined to do in the past. They pulled back the curtain, stripped away the myth, dismantled Pete Rose the icon, sold off the pieces, and revealed the man, naked and broken, for who he was, for who he had always been, though no one had ever dared to say it out loud for fear of tarnishing America’s pastime. Pete wasn’t working-class. He was maybe low class. He was uneducated and unpolished beneath his New Money shine. He was consorting with a screwball collection of bookies, railbirds, lackeys, dope dealers, and wannabe mobsters, and he had surrounded himself with a small group of young admirers who were thrilled to be his friends and were willing to do anything to protect him. They would satisfy Pete’s addictions and keep his many secrets. They wouldn’t tell anyone that he was sleeping with young women, that he was betting on baseball, and that he was lying about all of it.

These revelations, still to come, would forever alter the game, ruin Pete Rose, change life in the proud baseball town of Cincinnati, spark endless debates about fame and forgiveness that still linger decades later, and mark the end of the age of innocence in sports. By the time it was over, Pete was no longer just a man; he was a fault line, separating the past from the present, the time of heroes from the time of cheaters. Nothing in American sports would ever be the same again. We wouldn’t even think about gambling the same way.

Still Banned From Baseball for Betting, Pete Rose Starts Gambling Podcast

MLB’s all-time leader in hits will host “Pete Rose’s Daily Picks” for Quake Media starting this weekSports wagering is now legal in almost every state. In some cities, baseball fans can place bets on the game at kiosks inside the stadium. In most states, people can wager with the flick of their fingers on their phones while they cheer from the cheap seats or from just behind the dugout, and baseball, once opposed to gambling in all its formats, isn’t frowning on the new craze. It’s actively promoting sports gambling with corporate partnerships and in-game graphics broadcast on national television, giving viewers live betting odds of the current batter’s chances of hitting a home run in that very moment. There’s simply too much money in play not to be involved. In 2023, fans in America wagered more than one hundred billion dollars on sports, enough money that they could have pooled their cash to buy the Cincinnati Reds a hundred times over or purchase every single Major League Baseball team — and still have billions of dollars left in their pockets.

These are changes that no one saw coming — least of all Pete Rose, the baseball executives who put their careers on the line to investigate him, or Pete’s friends who were forced to make difficult choices in the white-hot klieg lights of a prying national media. As the FBI began to close in on Pete’s associates in the late 1980s, and baseball executives started asking questions of Pete himself — questions that they had ignored for years — everyone around Pete had to make a decision: Were they going to tell the truth and expose him for his gambling? Or were they going to lie and potentially go down with the man? What price were they willing to pay? What story were they going to tell? Which side were they on?

The answers to these questions changed people’s lives forever including Pete’s. And more than three decades later, these decisions still reverberate like shock waves through a universe that Pete created with his own hand. In this mythical place, Pete Rose is the sun, burning brightly in the center, and the people in his life, everyone else, are planets in orbit, trapped by shared history, Pete’s charisma, and above all his gravitational pull. Each was drawn to him for different reasons, and some in this universe are no longer in need of his light, of Pete’s warmth and attention. They orbit in distant rings, cold and dark. Still, they cannot escape, and certain disturbances like phone calls, say, from a writer, or fresh allegations, new stories set off a chain reaction. Those closest to Pete will still do what he says, while others on the outside — the dark planets gone cold — will crack up if they spend too much time remembering what it was like to live in the warm light of Pete’s sun. Put simply: people cry, break down, get angry or go off when they talk about Pete Rose. They love him or hate him so much that he has destroyed them.

But all that comes later, in the wreckage of this story, in the aftermath of one of America’s great tragedies. In the moment — Pete Rose’s greatest moment, on that night in September 1985 — everyone was happy, Pete most of all. He was a player at his peak standing on first base with the flashbulbs firing, and the people cheering, and the television broadcasters raising their beer cans in the booth behind home plate.

Somewhere in the stands, Pete’s mother hugged friends and family. In the seats around her, strangers embraced, too, and at some point Pete couldn’t take it anymore. He looked up at the sky and then buried his face into the shoulder of his first-base coach, his longtime friend and former teammate Tommy Helms. “I don’t know what to do,” Pete told Helms, as the ovation continued at Riverfront Stadium unabated. “That’s okay, boss,” Helms replied. Pete didn’t have to do anything anymore. “You’re number one,” Helms assured him. “You deserve it all.”

Excerpted from Charlie Hustle: The Rise and Fall of Pete Rose, and the Last Glory Days of Baseball by Keith O’Brien. Used with permission from Pantheon Books.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.