A study conducted by the University of Lleida in Spain last year confirmed that the younger you are, the more likely you are to drive in a risky way. This will not surprise you, in the same way it doesn’t surprise car insurers. Even more obvious was the finding that an aggressive personality is associated with risky driving. A less obvious outcome? Aggression in driving was only marginally more likely to be found in men than in women.

“That said, while men argue that they are more skilled than women in driving — and there’s some truth in that — hands down, women are much safer drivers,” laughs Lisa Dorn. “But the fact is that the gender gap in driving behaviors is now narrowing.”

Anyone who drives a vehicle has opinions about how other people drive, but Dorn thinks about these issues a lot — even more than the most emotional rush-hour commuters. Like the four-door Porsche 911 or the Lamborghini Marzal, she is one of a kind: an associate professor of driver behavior, and the director of the Driving Research Group at Cranfield University in the U.K.

“Most of my colleagues interested in this area appear to have left to work in far more lucrative fields,” she notes, “but I love it.”

Dorn’s work leads her to ponder questions like: Why do some of us tailgate the driver in front, but can’t stand being tailgated ourselves? Why do we feel invisible in our automobiles, and thus indulge in deep nasal excavation at stoplights, yet believe we see everything and everyone around us? She has looked into why, according to a study she conducted for Fiat, we feel better in a convertible — a style of car found to increase the driver’s self-reported sense of happiness by an average of 19%, even more for aggressive drivers — but how that can make us less safe drivers, too.

“Driving with the top down makes us feel more energized and that tends to make us feel more attentive,” she explains. “But even though you feel less cocooned from the world around you in a convertible, you’re also more inclined to speed.”

Is Semi-Autonomous Safety Technology Breeding a Generation of Bad Drivers?

As cars demand less and less input from drivers, our ability to react in emergencies diminishesWhile interest in driver psychology is growing — other academics are increasingly conducting research that is tangentially relevant — Dorn says the field is limited relative to similar research for other forms of travel. After all, governments are generally more directly involved in the management of airspace and railways; and those forms of transportation tend to kill a lot of people in one go when things go wrong, and consequently make headlines.

“Car crashes kill people every day, but largely get ignored,” she says. “That makes it hard for drivers to make a true assessment of the risk of driving. It also makes it hard to get funding to research [car] driver psychology. We just can’t get the traction yet to research the things we really need to understand.”

The Seriousness of a Simple Drive

The most important thrust of Dorn’s work is towards improving driver safety — on saving lives. This issue does not, she contends, come down to a lack of skill among drivers, despite what her studies confirm about our inability to assess our own aptitude behind the wheel. In any given sample, around 80% of people will claim, with statistical unlikelihood, that their driving performance is above average. The outcome of that mindset? That the laws of the road are seen to apply to those who are below average.

“Driving is actually an incredibly difficult task, yet people think it’s easy. We believe we have the skills to cope [with whatever driving challenges arise], but we don’t,” Dorn says. Indeed, we’re more vulnerable to car accidents once we’ve passed our driver’s license test, because we almost immediately start to overestimate our ability. “We think we will never crash, but we do. [For example,] police drivers are very highly skilled in driving technique, but their skills-based training doesn’t tackle their human behaviors.”

“A colleague of mine once said that there should be a six-inch knife coming out of the steering wheel. It is crucial that we feel the risk in driving.”

Lisa Dorn, associate professor of driving behavior

Dorn recently completed a long study that concludes that shock tactics don’t work either, at least in the context of driving: Attempt to confront drivers with how their poor mindset behind the wheel may have a very direct impact on their mortality, and the advice largely goes ignored. All the same, finding some way to pull drivers out of their distraction is vital — it’s the number one cause of car crashes, compounded by speeding’s reduction in reaction time; all the more so given that the higher we rate our own driving performance, the higher we rate our ability to do things other than driving, while we’re driving.

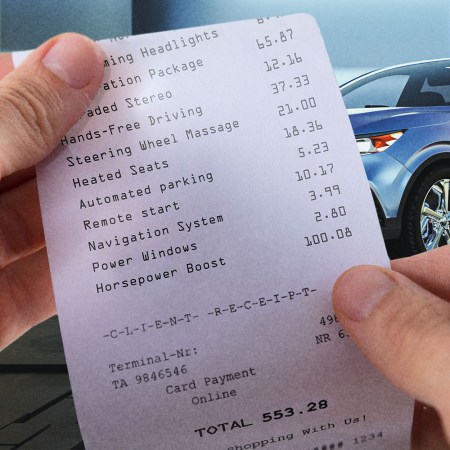

It doesn’t help, Dorn argues, that the car industry is skewed in its interests. Automakers’ true motivation is to sell cars. They see profit in making their products more comfortable and easier to drive, but that’s not necessarily what’s best for the driver.

“That’s seeking to take away human error, but actually taking away human input, which isn’t understanding the complexity of driver psychology,” she says. “If you give up control of the task to the car, you have less awareness of the need to take control. Conversely, the safer you feel, the more risk you’re willing to take. And we don’t feel the risk when we drive.”

“A colleague of mine once said that there should be a six-inch knife coming out of the steering wheel towards the driver,” she adds. “I wouldn’t advocate that, but it is crucial that we feel the risk in driving to keep pulling us out of any sense of distraction.”

Driver Assistance or Distraction?

Gemma Briggs, professor of applied cognitive psychology at the Open University, U.K., and a specialist in problems of attention, says that drivers are increasingly “sold the idea that [in-car] tech can ‘free them up’ to focus on other things, and the language used to advertise it tends to suggest it can do some of the work so the driver doesn’t have to. But the premise of all this tech is that the driver remains fully attentive all the time.”

This internal contradiction of modern driver-assistance technology is predated by one that many experience on a daily basis. “The subjective experience of driving doesn’t tend to match the objective processing and other demands it makes on us,” says Briggs. “Drivers often can’t remember details of journeys they have recently completed. This gives the illusion that — at least for some — driving takes little concerted effort or thought. This is problematic as the next logical step in this thought process is that as driving is so ‘easy’ a driver might have spare capacity to complete other non-driving related tasks.”

But, as most of us have had the occasional stark reminder, we don’t. There’s no such thing as multitasking, so much as rapid switching between tasks, typically to the detriment of all of them, which is a problem when you’re piloting one ton of fast-moving metal.

Dorn believes that the future of better driving comes down to improving our understanding of the peculiar interaction of vehicle and human.

“While we certainly take our personality traits and certain emotional responses with us into a car when we drive, driving can also trigger responses we certainly wouldn’t have in the world outside of it,” she stresses.

The Hidden Costs of Advanced Car-Safety Systems

Sensor calibration has completely changed the body-shop experience“There Are Some Systems a Car Should Not Have”

There are many questions that need answering.

We need to better understand why we get stressed when driving; why we’re induced to speed; why, when we’re driving on familiar roads, we spend less time looking around (and that’s not just off to the side, but right ahead); and why the driving behavior of young people changes, for the worse, when their peers are present. We need to know why we feel less accountable for our behavior in a car than out of it — research suggests that, as drivers, we’re more ready to dehumanize other drivers and pedestrians, akin to the behavior of some of us online — and why many of us get so angry when driving. If you really want a challenge, try figuring out why we’re more likely to be aggressive to the drivers of cars that are smaller or less expensive than our own.

One thing we don’t understand well at all? How the tech we’ve grown used to in modern cars shapes all of these behaviors over time.

“When we trust a system in our vehicle that allows us to drive in close proximity to a car in front, it’s no surprise that we tend to then also drive that close when the system is not engaged,” says Dorn, by way of example. “The fact is that the car industry — and research into driver behavior — really needs a period of reflection to better understand what systems going into cars now are really benefits, much as we all need to develop a better understanding of ourselves as drivers.”

Birsen Donmez, professor of industrial engineering at the University of Toronto and the Canada Research Chair in Human Factors and Transportation, agrees that, from the car’s end of the debate, the situation only looks set to get more complicated. We’re heading into a technological arms race of in-car systems, some of which make sense (crash-avoidance sensors, for when a driver hasn’t reacted in time) and some of which absolutely don’t (cruise control, “and any system in which you don’t have to even use the brake or steer”), not least because that reduces active driving to the more passive monitoring of systems, and humans are very bad at that.

“We can design cars that better support driver behavior, but there are simply some systems that a car should not have,” Donmez argues, adding that we’re now seeing — flipping the norms — the advent of in-car systems to monitor us drivers just to counter the effects that other in-car systems have on us.

“But the fact is that the urban environment especially can be very demanding for drivers, because there is a limit to our cognitive processing and there are too many things to pay attention to,” she says. Last year, she conducted a study of drivers’ eye movement at intersections and found more than half failed to look for cyclists or pedestrians at all. “What we really need to do is change the actual infrastructure of our roads. Yet these are big systems, of course, with lots of decision makers, and they’re very, very hard to change.”

If pressuring the car industry to change may prove an uphill battle, drivers themselves at least can be changed, Dorn says, albeit not overnight. “Some one-off intervention isn’t going to change behavior,” she stresses, but the right nudges can help.

A project she led with a leading British insurance company suggests that safer driving can be encouraged by offering discounts for driving a car fitted with a “black box” recorder — so-called telematics-based insurance; or by offering driver coaching interventions periodically by smartphone; or, particularly with younger drivers, by gamifying driving through a kind of leaderboard challenge.

The problem with all of this? Getting us all to go along. Dorn argues that the car is so totemic of our sense of freedom that we’re not exactly open to changes that feel like constraints — the car industry and its lobbyists even less so. Automakers could, she notes, easily make it impossible to use a phone while in a car, but they don’t want to lose sales or, like lawmakers too, face down driver disgruntlement.

It comes down to what she calls the “traffic culture” of the U.S., with its drive-ins, drive-thrus and the romance of the open road. But, she adds, while it may be outpaced by most, if not all, African, Middle Eastern and South American countries, the U.S. has the highest car accident rates per capita in all of the developed world. That’s likely no coincidence.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.