The big brown bear ambled up the makeshift trail, seemingly making a beeline for our group. Topping 600 pounds, he was one of the largest bears we’d seen in our few days in Lake Clark National Park.

Johnny Haws, our guide for this afternoon excursion, gathered us close together, with him in front and on one knee. In the rush, I’d left my backpack behind, and now the bear was walking up to it, giving it a serious sniff. My mind raced — did I leave any food or other contraband in the backpack? Had someone stuffed a salmon in my pack as a joke when I wasn’t looking? Were we about to get a Cocaine Bear sequel in real life?

Luckily, after a quick and quiet reprimand from Haws — “No bear. C’mon, get going.” — the coastal grizzly continued walking to the same trail we’d trekked up maybe 20 minutes prior. Later, as we began walking back to the truck, we noticed two fuzzy ears poking out of the tall grass; that same bear was blocking our path. We would wait. After the bear had his fill, he began returning from where he came, forcing us to step off the trail to allow him by. As he strutted past just a few yards away, I could swear he looked at Haws, issuing a silent, malice-less reminder about who was really in charge here.

Moments like this are the exact reason I traveled thousands of miles to come to Natural Habitat Adventures’ Bear Camp. Surrounded by Lake Clark National Park and north of McNeil River Game Range and Katmai National Park, this may be the highest concentration of coastal grizzlies in the entire world. And because the bears aren’t hunted in these parks, they’ve developed no fear of humans. In fact, they’ve become so used to humans watching them that they rarely give us a second glance as they go about their day. For a bear-obsessed photographer like me, it’s nirvana.

Getting to the remote camp isn’t as easy as driving your SUV to a lodge. After flying into Anchorage, I had to take a second commuter flight to Homer, where I was soon climbing into the co-pilot’s seat of a 10-seater DeHavilland Beaver, designed to take off and land on short stretches of dirt or beach. (No, I don’t know how to fly a plane.)

Flying low over the Cook Inlet into Chinitna Bay, we saw multiple bears digging for clams in the low tide. Our excitement grew as we realized we’d be seeing many more in the coming days — and from a much closer distance. Minutes after landing, we hopped into a modified extended cab pick-up and drove to the end of the spit, where we saw the same bears, now just brown specks in the distance. It wasn’t long until one of those specks began getting larger, as she had apparently eaten her fill and was heading back to shore.

How to Spend a Perfect Weekend in the Epicenter of the Great Bear Rainforest

British Columbia’s best-kept secret is packed with wildlife, adventure and Indigenous cultureSeeing this magnificent sub-adult coastal grizzly took our collective breath away as she passed within a dozen or so yards of us. For the dozen in our group, it was an awe-inspiring moment, but to her, we were just part of the scenery. She continued walking past us and over a small rise on the beach, where she was soon lying in a makeshift bed we’d noticed earlier. The only thing we could see over the hill was her paws and tip of her snout as she stretched before taking a post-meal nap. It was one of the most adorable sights I can remember seeing.

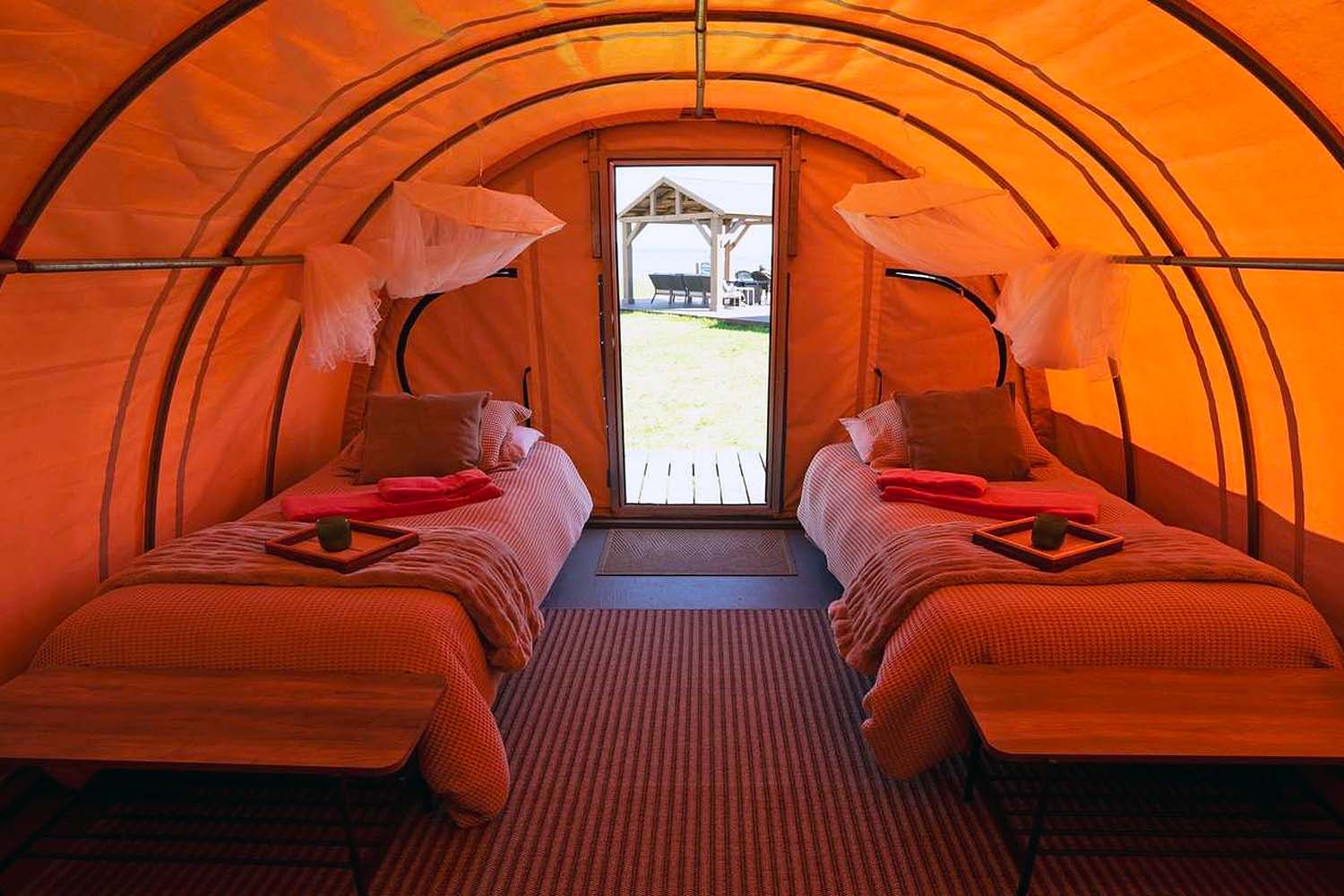

After the high of that initial encounter, we headed back to camp to settle in. Bear Camp is mostly made up of a series of 20-foot waxed canvas tents, each named after a significant person in the history of the national park or NatHab founder Ben Bressler’s life. Each of the guest tents contained two cots with mosquito nets, two clothes racks, two rechargeable lanterns, a portable propane heater and cartridge toilet, for “midnight emergencies.” (Liquids only, please.) Anyone suffering from anxiety would love the bedding; temperatures would dip into the 40’s during the night, but the hefty weight of the blankets kept us warm.

In the center of those tents stood a larger dining tent where we had our meals and congregated in our down time. The kitchen, two outhouses and two showers were the only semi-permanent structures in the camp. All toiletries and food had to be stored in a secure area just in case a bear got through the fence in search of a late-night snack. I asked Haws if a bear ever made it into camp, and he sheepishly admitted it may have happened once or twice.

About 500 yards behind camp, staff built a two-story viewing platform overlooking a massive meadow across the creek. Because of the constant rain, we spent most of our time observing the bears here, where they munched on the nutritious sedge in the meadow or mommas fished in the creek for salmon while their hungry cubs murmured their impatience from the shore. A mile or so in either direction, the National Park Service had their own viewing areas, which offered different vantage points of the same creek and meadow.

We saw up to a couple of dozen bears each day, many of whom were daily return visitors. During our four days at camp, we got to know certain bears quite well; one bear, whom we named Rip Van Winkle, spent almost our entire second day napping on the shore. He spent so much time asleep that we actually began worrying about him. Every time we returned to the platform, he’d be in the same place, only lifting his head long enough to identify who was making the racket. Even Haws and our other guide, Jessica Morgan, expressed concern. Unfortunately, even if the bear was sick, we couldn’t intervene; we were here only to observe, not interfere in nature. Thankfully, by the end of the day, Rip had apparently gotten enough beauty sleep. When he finally stood, we collectively sighed in relief and silently cheered, before he ambled away in search of more salmon.

For each of the clients in my group, this was the trip of a lifetime, or in Diane Parrillo’s case, a past life. Parrillo swore to all assembled she’d been a grizzly in a previous existence and hoped when she was again reincarnated, she’d return to a life of fur and massive paws. For British couple Steve and Chris Campling, photographing the Lake Clark brown bears was just as exciting as going on an African safari.

“We’ve done other close-up animal encounters, like trekking to see gorillas or a walking big-cat safari, and this was right up there with the best of them,” Steve said. “You get an amazing adrenaline buzz (in the moment), but it’s the memories that live in your head forever after that keep us coming back.”

As I scroll through my photos, the moments surrounding nearly each image — the smell of rain and wet fur, the sounds of chuffing male warning another bear to back off, the excited glances of the other guests — remain etched in my memory as well.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.