My first Playboy was the June 1994 issue. A 21-year-old Jenny McCarthy was declared “Playmate of the Year,” a series of female firefighters revealed what was under their flame-resistant jackets and Elan Carter, the “Playmate of the Month,” disclosed on her centerfold data sheet that she had a 34C bust and loved to “be seductive.” Because my parents sometimes read my work I won’t disclose how, at 15 years old, I was able to secure a copy of the magazine, but I will write that at that age I was, uh, excited by those pictorials.

Nearly three decades later, the last of which I’ve spent as a journalist, I look at the same edition on Playboy’s website and find myself aroused — in a sense — by different details.

There’s a lengthy interview with whom the publication called on its cover “The King Of Pop Music.” While for years that title had been bestowed upon Michael Jackson, on the strength of his fairly traditional pop oeuvre, in 1994 Playboy fixed the crown atop the head of country star Garth Brooks. It was something of an editorial flex, coming a few years after SoundScan recalibrated what was big in American music by counting individual album sales via computer as opposed to Billboard’s previous approach of calling record store owners for guesstimations. The modernization of the charting process pole-vaulted country — as well as rap, grunge and heavy metal music — into peak positions.

Also appearing on the June 1994 cover of Playboy in headline form: “The Sordid Confessions Of An Internet Addict.” The corresponding piece spans five full pages inside, and describes a 22-year-old woman’s obsession with “e-mail” and “on-line” forums — those hyphenations long discarded in mainstream print. The World Wide Web was so new back then that writer J.C. Herz, who’d become a prominent tech journalist and rock critic, needed to provide a lengthy description of it in her introduction. “The Internet is not an on-line service or even a single computer network,” she wrote. “It is a web of systems linked together by software and phone lines.” The internet reached a whopping 20 million people, she reported, many of whom were, like herself, accessing it through college-based hard and software infrastructure. “Jesus shows up occasionally,” Herz observed. “But that’s not surprising, considering half the people on the Net think they are Jesus.” (Her Harvard-senior self would have been totally mind-blown by Twitter.)

These two features from a single edition of Playboy that happened to be my first contextualize just how entrenched the publication was at the cutting edge of journalism in its heyday. If I still owned a subscription — I bought one immediately after shedding the age designation of “minor” in 1997 — I’d definitely “read Playboy for the articles,” as the old joke goes.

Unfortunately, there’s no Playboy magazine to subscribe to. After being relegated to bi-monthly editions, then becoming a quarterly for a while, it was discontinued completely by the company in 2020, ending a 66-year run of circulation. Playboy eventually dispensed with its digital editorial pages as well. There are still naked ladies on the website — decidedly less-airbrushed ones compared to what I was first exposed to — but no fresh zag commentary on culture anywhere, no deeply-dived wells of critical information about politics or sex trends. That’s all been replaced primarily by digital consumer goods outlets.

On Playboy.com there’s a Playboy apparel store, the Tokyo Club’s Playboy-branded streetwear store and two additional lingerie stores, Yandy and Honey Birdette — brands that Playboy’s parent company, now the PLBY Group, acquired in the past few years.

Playboy and Beyond: How Adult Magazines Are Evolving for Millennials

Attitudes toward sexuality are changing. Nude mags are trying to keep up.As of yesterday morning, Lovers, an online and brick-and-mortar chain the PLYBY Group purchased in 2021 that stocks sexual wellness products, is selling Playboy’s first line of sex toys. Dubbed “Playboy Pleasure,” the line’s featured products include 17 different vibrators for people with vaginas, five penis toys — three cock rings and two strokers — and six butt plugs. Playboy’s marketing department says the items have “sleek designs,” as well as “shimmering opalescent and jewel-tone colors.” Summoning the company’s recently launched tagline, they also say the toys boast “functionality with pleasure for all at its core” (italics are mine).

“We’ve got something in this product offer for everyone,” says Ashley Kechter, PLBY Group’s President of Global Consumer Products. “It’s really elevated. It’s something that we’ve got our beliefs and values inside.”

Playboy Pleasure, which includes a number of additional products, from kegel balls to lube to toy cleaners and beyond, is a checkpoint in what Kechter calls the PLBY Group’s “migration” over the past few years toward a promised land of greater inclusivity. Manufacturing and marketing sex toys for “everyone” — an endless sea of potential customers — is not only good for strengthening the company’s bottom line, but it also moves the Playboy brand further away from its legacy, one that’s peppered with exclusivity and alleged impropriety as well.

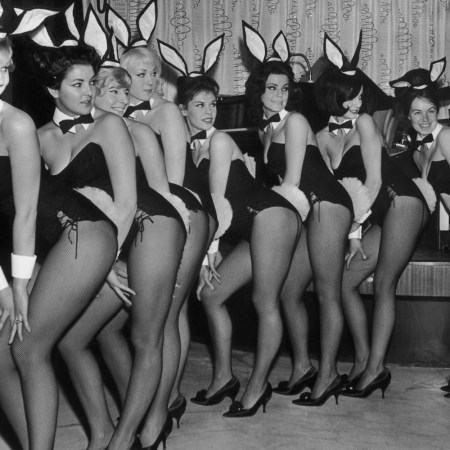

Playboy magazine catered to a demographic that Newsweek once described as “upwardly mobile white men,” which is precisely what founder Hugh Hefner was when he launched the publication in 1953. But Hefner became a staunch advocate for free speech to the benefit of all Americans. While that cause was at least somewhat self-serving, it’s notable that Hefner also used his profile and the company’s clout to promote Black voices at the height of the Civil Rights Era. Martin Luther King Jr. himself once sat for a Playboy interview.

Hefner’s relationship with the female gender, however, was roundly criticized, particularly later in his life and upon his death in 2017. He was later accused of various sexual improprieties, including rape, in a 2022 documentary. When that round of allegations was made public, a few years after the last of the Hefner family had exited the Playboy company, the organization said in a statement, “Today’s Playboy is not Hugh Hefner’s Playboy. We trust and validate these women and their stories and we strongly support those individuals who have come forward to share their experiences.”

Rachel Webber, the PLBY Group’s Chief Brand Officer, tells me, “There are many elements of our history which we’re immensely proud of, and then there are some elements that are unworthy of our principles today.” She says the PLBY Group’s focus is on “living up to the positive parts of the legacy and taking the core DNA around those values” — free expression, sex positivity, equality — and “leaning into advancing that mission of pleasure for all, while simultaneously not hiding from the complexities of the past.”

For the PLBY Group, that has meant behind-the-scenes hiring of more women and young people, as the New York Times covered in 2019. Now we’re getting front-facing sex toys, marketed toward the straight white men who buttered Playboy’s bread for decades, but also women, as well as members of the LGBTQ+ and BIPOC communities.

“They’re trying to find their way in order to stay alive,” says Steven Miller, Director of Undergraduate Studies, Journalism and Media Studies at Rutgers University. “That’s one of the battles we [in the journalism industry] have every day.”

But this brand survival tactic of pivoting toward consumer goods has meant one less place citizens can be informed through the written word, coming at a time in which many other print publications have slowed publication or outright met their demise. That’s not great for democracy.

“Hefner made it a point to print articles and interviews with people of note who had a significant impact on society. It wasn’t just about women posing naked,” Miller says. “With the advent of the internet, you lack authoritative sources for the general public.”

According to some studies, Miller notes, the internet has helped fuel an increasing number of conspiracy theories, in part because information sources that are not trustworthy are as easily accessible as those that are. This development is among the reasons for social instability in the U.S. these days.

But from a print publication perspective, Playboy magazine was long playing with house money.

“Magazines historically go out of business very quickly,” Miller says. In fact, the first two magazines in American history — first published three days apart in 1741 by Benjamin Franklin and Andrew Bradford, a printer who founded the first Philadelphia newspaper — only lasted a few months each. Any publisher tempts fate by launching a new print magazine because, Miller says, they are expensive to produce.

“Print magazines have always been a luxury,” says Aileen Gallagher, Chair of Magazine, News and Digital Journalism at Syracuse University’s Newhouse School of Public Communications. “People need newspapers to know what’s going on in the world around them, but you don’t need magazines.”

That’s not to suggest society shouldn’t have magazines either.

“Magazines have always done their best work with evergreen stories, where you have in-depth exposés or profiles of significant figures,” Miller says. “You can do [that] online, and a lot of people use tablets [for reading], but for others it’s so much better to have the magazine.”

People — myself included — like the tactile feel of a magazine, as opposed to reading words off of a screen, which when done in long spells may cause bodily harm. Miller observes that if a person reads a portion of a 10-page article in a printed publication and puts it aside for a time, it’s easy for them to return to the same spot in the piece. Online, they have to scroll to find it again, and sometimes links change making the article difficult to locate at all. (Apparently this is something Playboy is aware of because browsers of its digital magazine archive are treated to interactive features like the ability to flip pages by clicking a corner and dragging it across the screen with a mouse.)

Meet the Artist Behind Doc Johnson’s Sex Toys

Have you ever thought about who crafted the veins on your dildo?Of greater importance to journalism, though, is the mass delivery of reliable information to the public, through one means or another. In the grand scheme of things, that’s something Gallagher isn’t too worried about.

“To me, the style of magazine journalism is very much alive and well, it’s just in different formats,” she says. “What people love about magazines is also what people love about digital media in that it has strong point-of-view, a really creative approach to telling stories and sharing news and information. There’s a big visual component to it, strong narrative focus, which you find from Netflix documentaries to true crime podcasts, even to the service journalism of TikTok and YouTube.”

In addition to seeking cultural and political insights, the men of the past who read Playboy turned to it for lifestyle advice. Gallagher says they sought answers to questions like, “How do I dress? What kind of stuff should I have in order to be the kind of man I imagine? What should I watch and listen to? Where should I live?”

Now, “that stuff gets served by any number of outlets,” Gallagher says. In fact, the publication you’re currently reading was invoked as one example in my conversation with her. And there’s countless corners on the World Wide Web of today for pornography, that other thing Playboy was known for.

Print magazines — pornographic or not — are generally struggling today because revenue from print advertising is drying up. Brands are increasingly finding their customers through digital marketing means. So, Gallagher says, “what we’re seeing now is print is one aspect of a [journalism] brand that is bundled to subscribers who are also subscribing to the digital product, and the print is kind of an add-on.”

But there’s also been a rise in quarterlies, Gallagher says, that are “even more luxurious.”

“Essentially now we’re asking people to spend what you would on a book, so in turn they have to be more substantive and lasting,” she says.

Though Playboy unsuccessfully tried this approach in the recent past, there’s evidence of excitement around the format. For example, the recently relaunched Creem magazine, which covered rock music in print on a monthly basis from 1969 through 1989, is available in quarterly print editions, though it publishes on the web as well.

Gallagher also notes the recent success of “bookazines” — one-off, in-depth magazines, each devoted to a single topic, and notably printed by outlets like Time magazine. They’re a reason for optimism that the printed word in journalism isn’t bound for the morgue. Bookazines are sold at a higher price than traditional magazines. Thus, print ads, which consumers despise, are not required for profit. A 2021 article from CNN Business on the bookazine phenomenon — not a new one in the print world, necessarily — highlights that they represent an “intentional purchase,” a growing contemporary consumer behavior trend.

Should a journalism publisher want to remain devoted to print as opposed to online distribution, trends be damned, they might want to consider what seems to be at this point a counterintuitive measure: packaging information exclusively for print and not bothering with online at all.

“If you have an article that’s a one-time interview with Taylor Swift only in the print edition, that might get that audience” to buy it, says Miller. In other words, he adds, make the publication a “must-have.”

The PLBY Group’s not in the print game at the moment, but it’s still a brand that denotes some authority in the sex space. Its dalliance in sex toys — after decades of selling Playboy-branded merchandise, primarily apparel, well before the magazine was discontinued — may prove to be a natural maneuver with a payoff.

“If you don’t know what you’re doing, that’s a brand you trust when it comes to sex,” Gallagher says. “That’s not a bad play for them.”

She believes the PLBY Group wants consumers, especially younger ones, to “equate Playboy with sex and not equate Playboy with men.” While she says this will be “a pretty big pivot,” she concedes it’s “also one that shows that they have a good understanding of their marketplace.”

The company is apparently doing something right. Yearly sales revenue jumped 67 percent between 2020 and 2021, the most recently available annual data. And as we move further from the height of the pandemic, growth in sales revenue seems to be continuing. In all of 2021, the PLBY Group reported more than $246 million in sales, but last year sales for Q3 alone reached more than $63 million.

“People feel a connection to this brand,” says Rachel Webber, the company’s Chief Brand Officer. “We’ve been focusing our attention on capturing our audiences where they are.”

Turns out, like me, they might be more interested in Playboy’s editorial voice than it appeared in the recent past. Webber revealed to me small details of an unexpected plan for Playboy: printed word expression will make a comeback to the brand.

Executives have been thinking about, Webber says, “What would a magazine be like in 2023 and beyond?” Early indications are that written content will be generated through some extension of Playboy.com’s “Centerfold” creator platform, where, not unlike OnlyFans, users generate scintillating content themselves for subscribers. This approach to editorial publishing will allow the company to avoid a reliance on ad sales, Webber says, while staying true to Playboy’s “roots of being a creator-driven” brand and publication.

“‘I read it for the articles’ is very real,” Webber says. “We take that very seriously, being a steward of Playboy’s role serving as a thought leader in society.”

I’ll look forward to their crowning of the next “King Of Pop Music,” particularly after Bloomberg declared the current titleholder to be Justin Bieber. Playboy’s historically done better than that. And maybe they’ll hire me to roam around Web3. I’ve covered tech a bit, and a lot of the crypto bros in that space seem to think they’re Jesus, too.

You think I’ll get to meet Jenny McCarthy?

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.