It’s hard to blame Joey Gallo for hating the shift.

If you’re a baseball fan, you’ve likely felt personally victimized, in one big moment or another, when an opposing team decided to orient three men on the right side of the infield, or even four in the outfield (the formation resembling a 10-player beer softball league), in order to guarantee that they gobble up an out. These shifts are most often employed against low-average hitters, who tend to pull the ball in a predictable direction when they do make contact.

That just about sums up Gallo. An outfielder for the New York Yankees (by way of a trade with the Texas Rangers last summer), Gallo is a career .206 hitter who only hits the ball to the opposite side of the field 13.4% of the time. Unless he manages to bloop the ball into a stretch of grass, or smash it over the defense’s heads — which he does do well, at a clip of about 41 home runs over a 162 game season — he’s usually out when he puts the ball into play. Last season, during his time with the Yankees, his average on batted balls was an astonishingly low .193.

What’s more, the hopelessness of making contact seems to have messed with his ability to do so in the first place. Gallo struck out in 88 of his 228 plate appearances with the Bronx Bombers — nearly 40% of the time! He did do some bombing of his own — he hit 13 home runs during the team’s stretch run — but otherwise, the man was more or less an automatic out.

It’s a time-honored tradition for New Yorkers to dub underperforming millionaire athletes “bums.” Gallo has not escaped that ire. But recently, as MLB and MLBPA talks continue to head nowhere, and the scheduled Opening Day is now doomed, Gallo has indirectly defended his woes by meeting his kryptonite head-on. He thinks MLB should ban the shift. And he’s not wrong.

Here are some his comments from last week: “I get the defensive strategies. I do. I am 100 percent not against that … But I think at some point, you have to fix the game a little bit … I don’t understand how I’m supposed to hit a double or triple when I have six guys standing in the outfield.”

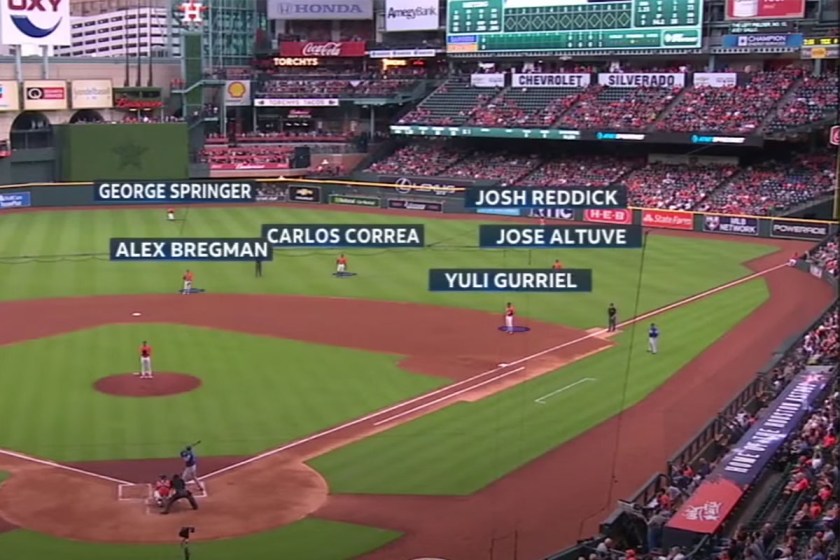

That last point might sound hyperbolic, but just below, take a look at an actual defensive formation the Houston Astros used to shut down Gallo, during a series in 2018. (You can check out the full video here, to watch Joey Gallo ground, fly and pop out all weekend, each time ripping the ball directly into the clutches of the Astros defense.)

Armchair hitting coaches have a typical response to this sort of visual: check out all the space on the left side! Why doesn’t he just bunt it? For starters, keep in mind that a bunt is best deployed as a premeditated decision. If a hitter’s going to commit to it, he’s going to step into the box and pull trigger on the first decent pitch in the zone. But if a decent pitch doesn’t come, and the count deepens, it’s in his best interest to call it off entirely, and let the pitcher tire himself out as he tries to reclaim the zone. At that point, why risk the uncertainty of a bunt, when you could earn a walk? (Not to mention, bunting later in the count comes with the risk of an accidental foul out.)

Today’s hitters aren’t taught how to bunt. They’re taught how to work pitch counts and force a pitcher to hammer the zone. Old heads like to opine on how the game’s ruined, how bunting is a lost art. Fine. But front offices started phasing sacrifice bunts out as early as 30 years ago, in response to research from Bill James and sabermetric acolytes that giving up an out just wasn’t worth it. You can’t exactly blame the Joey Gallos of the world (he was born in 1993) for coming up in a system where bunting wasn’t afforded equal attention to his natural ability to hit moonshots. Which is another reason our batter would really have to know he’s bunting beforehand — there’s no sense in standing up there and wasting strikes that could’ve been put in the seats. It would appear that managers prefer to take their chances on big swings, as opposed to shift-beating dribblers down the third base line.

Another criticism: why doesn’t he just hit it the other way? Indeed. And why couldn’t Joe Burrow sidestep Aaron Donald in Super Bowl LVI? Sports are hard. What may appear like minor adjustments to us are next to impossible for the professionals. Remember: scraping one’s way through youth tournaments, summer leagues, high school showcases and minor league ball to reach MLB is a statistical anomaly. Joey Gallo can play baseball. It’s not like he’s never been able to hit triples. During one season of low-A ball, he raked five. The reality is that hitting the ball hard is hard enough (Gallo is above average, at 92.7 mph on his career), but being able to direct the path of the ball is another order entirely, especially at the highest level. Players like Gallo, who surely once considered themselves all-around players, get pushed into corners as the talent condenses.

Good pitching is one reason. As is the hours of tape available to opposing teams determined to pinpoint your weaknesses. And the shift is another. Gallo could devote his offseason to an entirely different approach, in what would be an inevitably fruitless attempt to turn himself into Tony Gwynn or Derek Jeter, but he’s not being paid to perform like a top-of-the-order, inside-out-swinging ballplayer. He’s paid to hit the ball over the fence. Which is why one of baseball’s most contentious talking points, the shift, is partly responsible for the rise of one of its most contentious recent strategies: launch angle. Basically — if you can’t hit it past ’em, hit it over ’em.

Baseball purists, by and large, remain unimpressed by players determined to power their way out of shift misery. There’s a pompous, presumptuous expectation that good baseball players should be able to “figure it out.” Writing for The Atlantic, Jayson Stark says: “What the game seems to need is more DJ LeMahieus, whose specialty is the ability to control at-bats and put the ball in play … [but] the hitters who benefit most [from a ban on the shift] are ‘the hitters you least want to see in the game’ — those pull-happy left-handed hitters whose goal in life has nothing to do with slapping singles through a less crowded right side of the infield. On their road to 30 bombs and 175 strikeouts, they have no motivation to level their swing. Why would that change?”

That is … certainly a take. But it presupposes, erroneously, that the average baseball fans is pining for some Platonic version of the game, where all players have mastered the ability to hit the ball at all angles, and spray it to all corners of the field. For one, again, this is completely unrealistic. Listen to Freddie Freeman (quoted in that very article!), a contact hitter who won the National League MVP with a .341 average two years ago, explain how hard that is to pull off: “Everyone’s like, ‘Just hit the ball the other way.’ Um, so I’m trying to cover five pitches. They’re all moving. One is like 98 mph. And I’m just going to be able to do whatever I want and hit a ball to the left side? It’s not that easy. I wish it was, or I’d do it more often.”

Even if Freeman found that talent easier to come by, and his teammates were cut from the same cloth, what kind of fun would that be for fans? Baseball doesn’t get enough credit for its variance in size, or its diversity in skillset, because players rarely “match up” on the diamond. But much the same way that Allen Iverson and Shaquille O’Neal could coexist, and thrive, in a shared NBA, and we could appreciate and admire that fact, so too can the tiny Jose Altuve and the mighty Aaron Judge vie for the same American League MVP award. Different approaches are a good thing. If a player made it to the league, he made it to the league. There’s such a rush to discount so-called “three true outcome” players (guys like Gallo, who tend to strikeout, walk or hit a home run). They’re viewed as boring, they’re seen as unworthy of the time and attention of the game’s scholars. But lefty pull hitters aren’t the game’s ruin. The game owes everything to a lefty pull hitter, in fact. Remember him?

The real threat to the entertainment value of modern baseball is not guys trying to beat the shift. It’s the shift itself. It’s the fact that good hitters have to spend so much time trying to beat it — sometimes to the point where they stop trying to pull the ball into the air, which is the most valuable batted ball in baseball. We don’t need guys getting robbed of line drives up the middle or into gaps. We don’t need them trying to hit the ball the other way as an overdramatic response. And we definitely don’t need them bunting. We need them doing whatever the hell it was they were so good at that got them to the league in the first place.

The easiest way to see the impact the shift is having on the game is to go watch nine innings with your own eyes. (Though that might not be for a while, so don’t hold your breath.) Half-innings pass by, eerily smooth. A good rally always needed a bit of luck — now it needs a lot of it, plus a couple bad throws. Consider: teams averaged a little less than eight hits per game in 2021. The season broke the all-time record for most no-hitters thrown in a season. The only reason the average runs per game hasn’t completely cratered is players are still hitting the ball over the wall. Teams still scored at a rate of 4.47 runs per game; it was not uncommon last year, thanks to walks and home runs, for lineups to end games with more runs than hits.

Baseball has a lot on its plate right now, from rookie minimum salaries, to regional TV deals, to revenue sharing, to Spider Tack, to “bouncy” balls, to potential expansion cities, to games in London. The list goes on. One through line appears to be an insecurity about the game’s popularity among and influence over younger generations. But instead of being so damned nervous that games are too long, as if the mere fact of playing is such an imposition on the scattered attention of teenagers, why not lean into making the product more exciting, and if that means the game stretches a little longer (because guys like Gallo are actually reaching first base once a game) so be it.

At the moment, there’s limited data on what a shift ban would actually look like, and that data is imperfect, because it was collected in Double A, which is a very different league from MLB. For one, they don’t shift as much down there. Plus, MLB is populated with more athletic people who can take a defensive scheme and work it to perfection. Which means that some of the Double A data that suggested the efficacy of a shift ban to be inconclusive, should be taken with a grain of salt. MLB, for its part, looked at the data but is not letting it influence its vision of a potentially shiftless future. Commissioner Rob Manfred is not in anyone‘s good graces right now, but at the very least, he seems interested in pursuing limitations on the shift.

A comprehensive “offsides rule” could incorporate the Double A’s pilot program, plus a vision Manfred relayed last summer. In the minors, infielders weren’t allowed to stand in the outfield before a pitch was thrown. So — no four outfielders, no rover on the right side, no shortstop playing baby center field. Manfred, meanwhile, has talked about bringing the game back to what it looked like when he “was 12 years old.” He wants two infielders on either side of the second base bag at all times. Imagine a baseball game where the players on either team … played their positions?

It sounds insane, and yet, the more insane reality is that it will be an uphill battle to institute such a rule change with the league currently in disarray. If there was a year to try it out, it was back in 2020, the 60-game sprint where teams were so desperate to leave quarantine and get back on the field, that they accepted a bevy of bizarre new rules, including that runner-starts-on-second-base nonsense. But surely, if the league is willing to break new ground going forward — from batter requirements for bullpen personnel, to regulations on foreign substances, to the potential introduction of robotic umpires down the line — it can reasonably return to its roots, and embrace the original design of the game?

There were 6,882 shifts in 2013, compared to 59,062 in 2021. Nearly 5,000 hits were taken away by the shift last year. In the past, league officials have expressed doubt that banning the shift would foster a more “energized and entertaining game.” They’re dead wrong. Only John Smoltz, sitting up in the booth, wants to watch a pitching duel. And the real web gems, the ones that used to stuff half of Sportscenter‘s “Top 10,” were never a smug third baseman standing directly under what should’ve been a base hit; they’d show the true range and expertise of an infielder stretching his defensive coverage as far as it could possibly go. That was the contest — the uncertainty of where a ball would land, the desperation of a ballplayer to get there in time. These days, it’s all sorted out before the game on iPads. More than half of all balls last year were hit into a shift. Enough.

You can still call Joey Gallo a bum. Don’t worry. But at least hear him out. He played his first full season in 2017. He’s never known a league without shifts. So in a way, you could say we’ve never really known who the real Joey Gallo is. Here’s hoping one day we find out.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.