You know those cereal commercials where sugar bombs like Cinnamon Toast Crunch and Reese’s Puffs are said to be part of a “balanced breakfast”? That kind of sanctioned obfuscation is also rampant in the world of fashion, especially when it comes to so-called “sustainability.” You can’t step into a clothing store or peruse a menswear brand’s artfully designed website without running into some piece of clothing labeled sustainable, whether it’s a shirt that’s had its carbon emissions offset or swim trunks made of plastic water bottles. But what truly makes a piece of clothing sustainable?

The truth is, it’s impossible to tell. In the year 2021, we’ve finally reached a point where “sustainability” means nothing. It started out with great intentions — the clothing industry having to reckon with the environmental destruction caused by fast fashion, and frankly the production of all new clothes — but now that eco-friendliness is proving to be a money maker, many brands are in a race to see who can reap the biggest benefits with the least amount of sincerity. Big Cereal found a way to say candied flour flakes are healthy, and Big Fashion has found a way to say destructive clothing is good for the planet.

Some outspoken labels, like New York City’s Noah, have tried valiantly to fight back against this. In fact, the punk-skewing menswear brand went so far as to write a takedown of themselves in 2018, publishing a blog with the all-caps headline, “WE ARE NOT A SUSTAINABLE COMPANY.” (Besides the friendly fire, they’ve also committed to certain environmental initiatives, like 1% for the Planet.)

Not everyone can be Noah, but there are other menswear concerns that eschew the sensationalism and have simply set to work trying to find an alternative to sustainability. The question isn’t whether or not these are good ideas — we need all hands on deck for solutions to the climate, pollution, water and other environmental crises facing our consumerist world — it’s whether or not they can go beyond one T-shirt maker and take hold worldwide.

Circularity: Outerknown

Outerknown, the laid-back men’s (and women’s) brand cofounded by pro surfer Kelly Slater, has embraced the word “sustainability” since day one. As Slater writes on the website, “Sustainability is why the company exists.” But Megan Stoneburner, the company’s director of sustainability and sourcing, gave InsideHook a more realistic mission statement: “No brand has arrived at what should be the standard for sustainability. Our ambitions can never be about reaching perfection. Instead, we aim to constantly evolve and drive continuous improvement.”

The company’s current goal: to be fully circular by 2030. According to Stoneburner, that means keeping “[Outerknown’s] products out of the landfill and in circulation — forever.” (They’ve even made their roadmap available to customers.) The latest step towards that objective comes through the Second Spin collection, which uses a technology called CircularID Protocol from software company Eon that connects a garment to its history and materials. Just scan a QR code on the tag, like a polo I tested, and you can see what it’s made from (in this case, recycled and organic cotton), where it’s been in the crop-to-consumer process (Austria, Turkey, India, Morocco, Spain and the U.S.) and options for recycling or reselling the garment (that’s currently in progress). But circularity here focuses on more than just the product itself.

“The three main pillars outlined in our strategy to be fully circular by 2030 are to 1) lead innovation 2) embrace circular models and 3) champion fair labor,” she said. That includes increasing their transparency and traceability.

Traceability: Asket

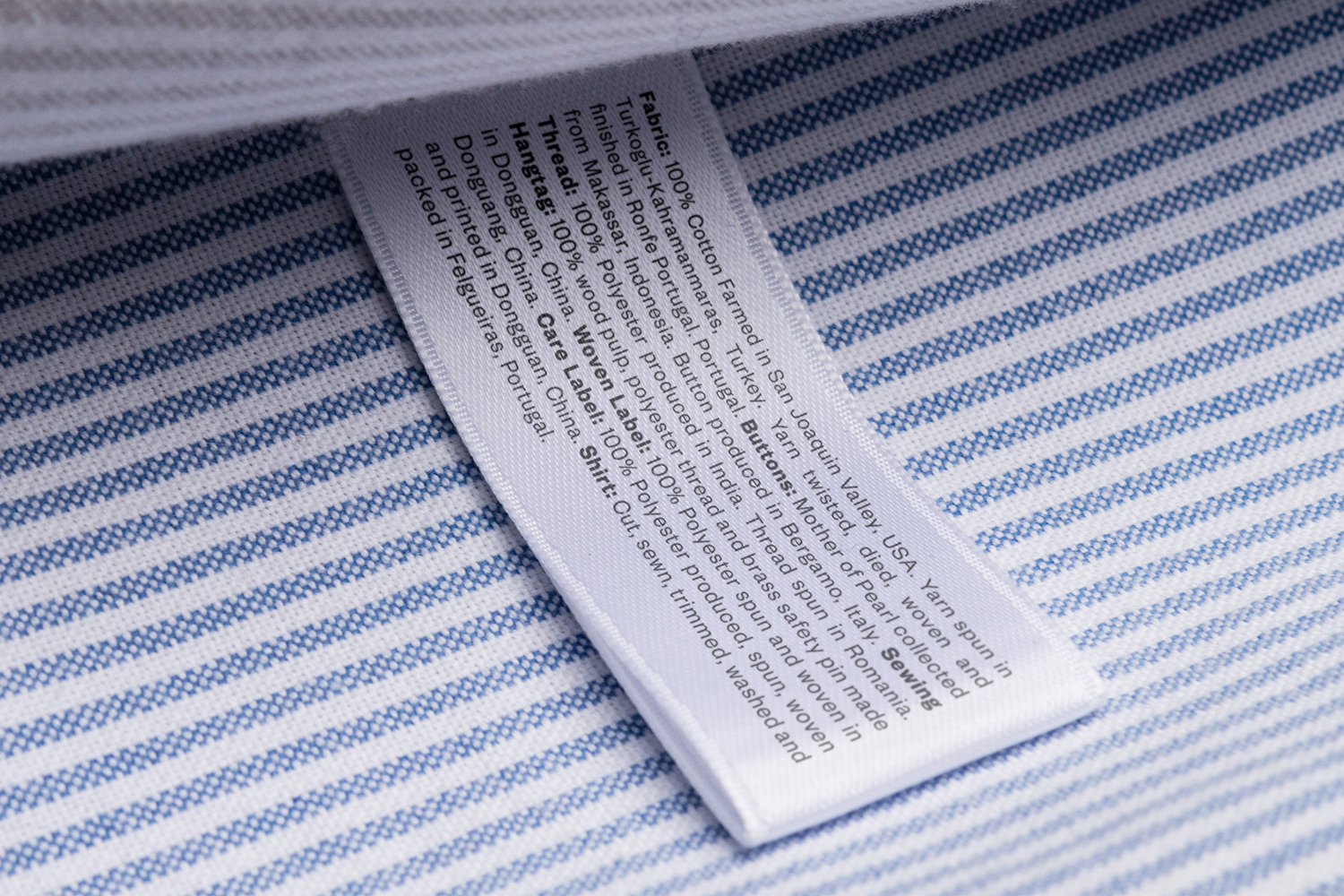

While other brands are starting to adopt the word traceability, the Swedish menswear (and recently announced womenswear) company Asket is the embodiment of the term’s ideal. When we recently spoke with co-founder Jakob Dworsky, he made it clear that their overall goal is transparency — it’s one of the six words on the top bar of their website — and the ability to trace a garment from the raw material all the way to your doorstep is a key component of that.

“Transparency is as much about where, how and by whom something is made, which is what we call traceability, but also about what [products] cost you, what they cost us and what they cost the planet,” Dworsky said. “But traceability in itself is really the foundation of that because how could you know that a garment is climate neutral or sustainable if you don’t know where it’s made and how, and by whom? Making those claims without traceability, I would say, is borderline greenwashing.”

Asket doesn’t claim to be 100% traceable yet (they’re at about 86% currently), but it varies from piece to piece. The basic T-shirt, for example, is just 67% traceable while the Merino Sweater is at 100% thanks to a bulk wool purchase. But like Outerknown, Asket does more than just one initiative; they also track things like carbon emissions, water consumption and energy usage, and they created the Revival Program where old clothes can get sent back.

Quit Single Use: United By Blue

Similar to Outerknown, United By Blue’s environmental mission is the reason the brand exists. As the name suggests, the Philadelphia company is in it for the health of the ocean; their hook is that for every product purchased they’ll remove one pound of trash from oceans and waterways. At the time of writing, a ticker at the top of the website says that’s added up to over 3.6 million pounds.

More consequential than cleaning up after the trash is already floating up on the beach is the company’s Quit Single Use Task Force, an audit they’ve been conducting for a couple years in an attempt to eliminate single-use plastic from the business, from their own plastic bags used in shipping out organic cotton board shorts to the shrink wrap on industrial pallets. In a recent update, they admitted to having a tough time with the material during the pandemic — when disposable items came back in a big way — but that they’re back on track for 2021.

Whether or not you decide to sample the wares of these three brands is not the point (though supporting companies doing good with your hard-earned dollars is always recommended). The point is, the next time you think about buying something “sustainable,” take a moment and try to find out what that actually means. Because, to echo Inigo Montoya, it probably doesn’t mean what you think it means.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.