Out of all the chaos surrounding the historic arraignment of Donald Trump, one single image has managed to captivate the nation. It is not a photograph of the former president from a major news organization, nor is it a smartphone photo from a protester outside the Manhattan Criminal Courthouse. Instead, it is a sketch — hastily drawn, but one that fully captures the emotion and weight of the moment, as evidenced by it going viral on social media and being chosen as the next New Yorker cover. The illustrator, Jane Rosenberg, a legend among courtroom sketch artists, has been preparing for this her entire career.

Elyssa Goodman interviewed Rosenberg for InsideHook in 2020, after Trump’s chief strategist, Steve Bannon, had his own arraignment hearing. Goodman describes that experience as “particularly stressful.” But that assignment, as well as Rosenberg’s 40 years in the business sketching everyone from Harvey Weinstein to Bill Cosby, prepared her to draw what could be a defining image in the life of Donald Trump, and in the history of the country.

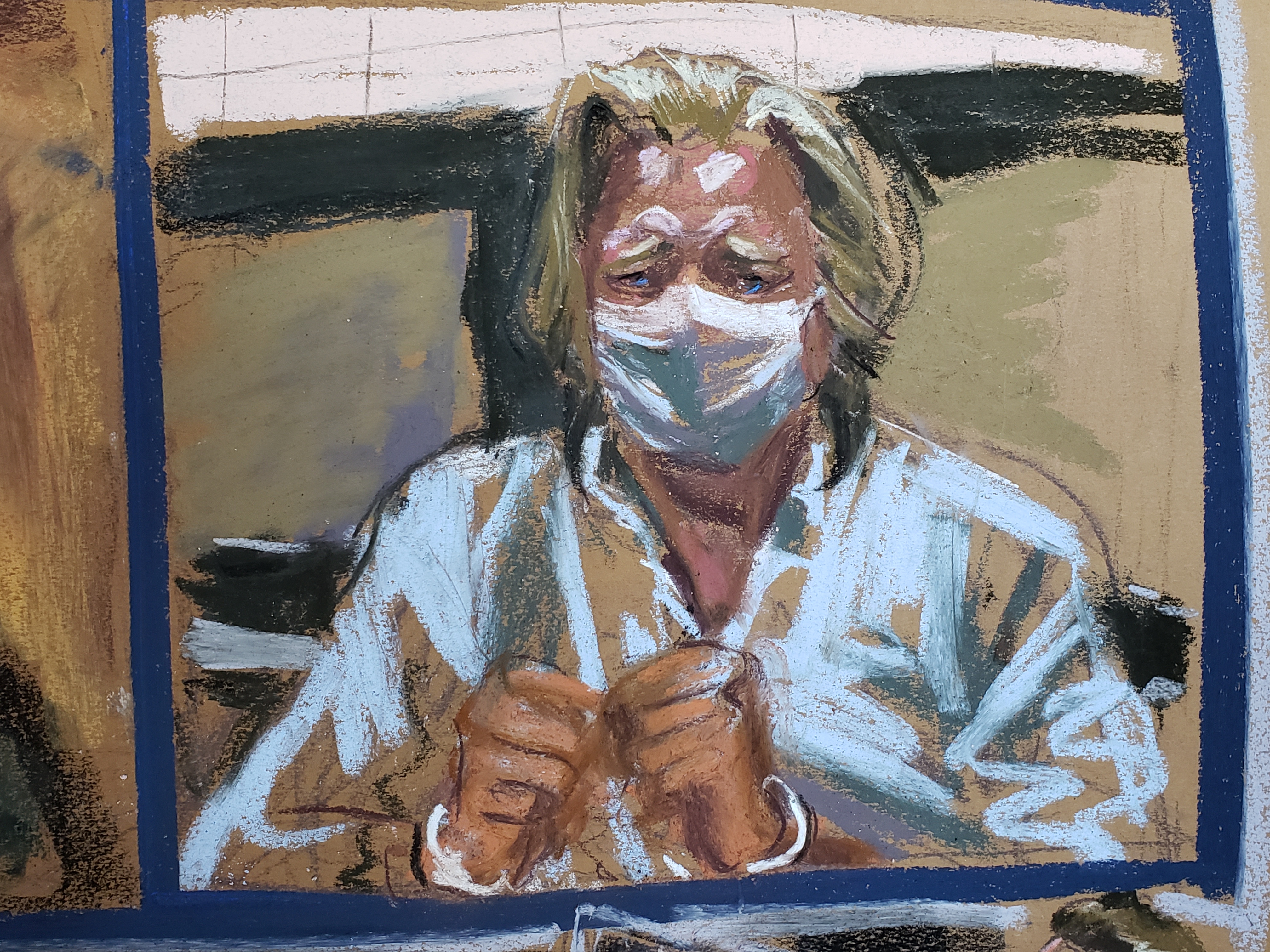

Jane Rosenberg didn’t know if she’d make it. On August 20, 2020, she was two hours outside of New York when she got an email about the Steve Bannon arraignment hearing for conspiracy. Time was ticking, traffic was raging and her stress was mounting. But luckily she slipped into Manhattan’s federal court with plenty of time, her portfolio, paper, pastels, paper towels and binoculars in tow. Soon her courtroom sketch of the former White House chief strategist, who that day was indicted for fraud, ran rampant across the internet. Clad in a white Oxford shirt, white mask and handcuffs, his shaggy hair made way for pleading eyes, a pathetic sight rendered almost expressionistically by the skilled hand of its artist.

But Rosenberg will tell you that her job is only to draw what she sees.

“My job as a courtroom artist is to try to remain neutral all the time. I’m not trying to have an opinion in my work,” she says. “If somebody displays emotion, then that’s what I have to try to capture.” And after 40 years, Rosenberg has seen a wealth of moments both emotive and historical.

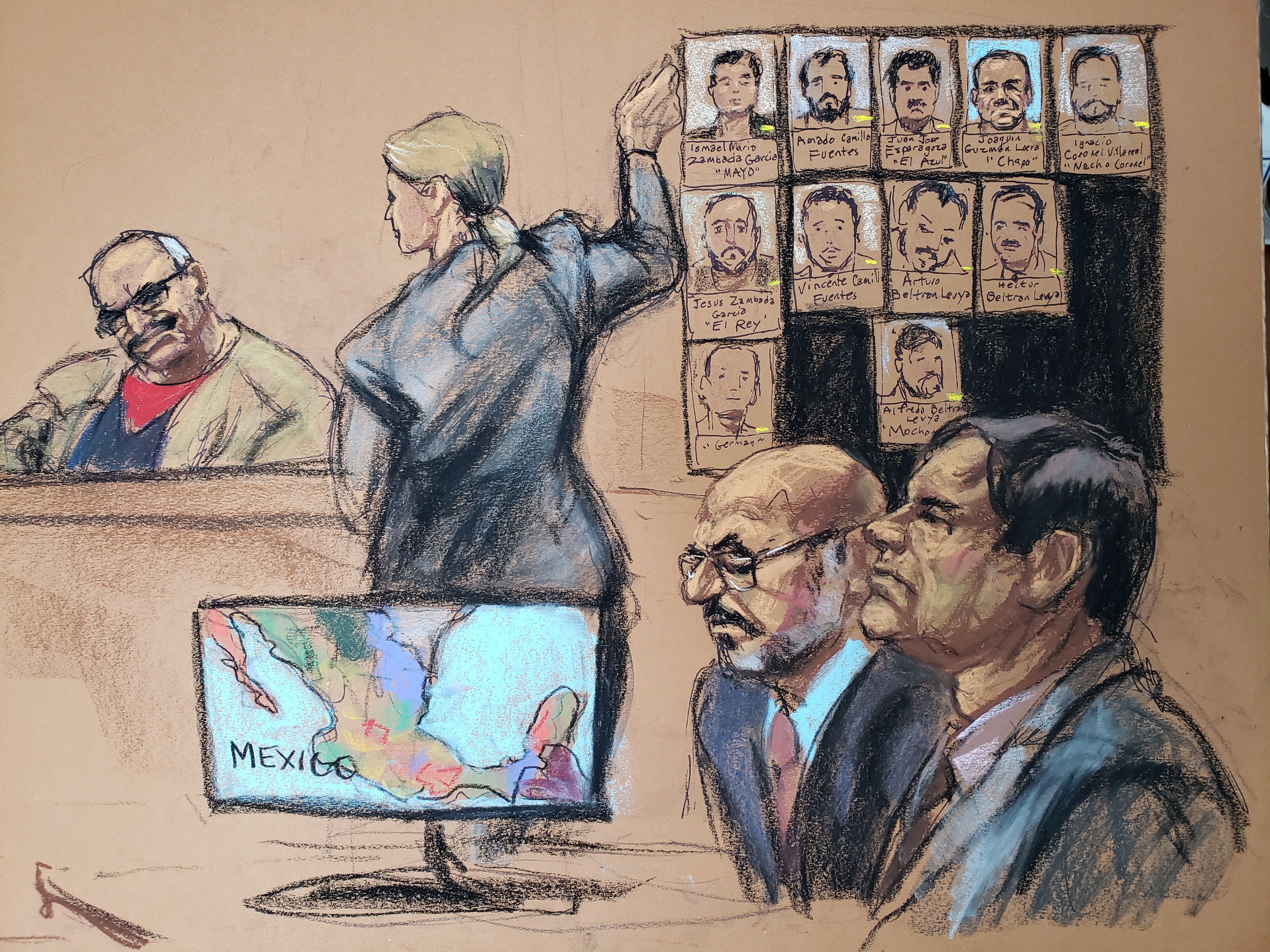

She was at the trial of Mark David Chapman after he murdered John Lennon. The 1987 Tawana Brawley trials. The 1993 Woody Allen-Mia Farrow custody hearings. Martha Stewart’s 2004 trials for insider trading. The 2005 fraud conviction of WorldCom CEO Bernard Ebbers. Tom Brady’s Deflategate scandal in 2015. Bill Cosby’s 2018 sentencing. El Chapo’s 2019 sentencing. Harvey Weinstein’s rape trials earlier in 2020. Anthony Weiner. Tekashi 6ix9ine. Martin Shkreli. Bernie Madoff.

“I also have an archive of original courtroom sketches that sometimes I’ll look back on, and I’m remembering, ‘Oh my god, I was really there back then?’” she says. “I have these things in my files…. I’m always surprised I have some gems in there.”

Rosenberg began her career as what she calls a “starving artist” after graduating from college with a fine art degree and taking classes at the Art Students League of New York. She drew portraits on the beach in Provincetown, Massachusetts, and recreated Rembrandts and Vermeers on the sidewalk with pastels on Fifth Avenue near the Central Park Zoo, leaving a hat out for tips. But when she saw courtroom artist Marilyn Church speak at the Society of Illustrators in New York, she was driven to become one herself. “I looked in the mirror and when I came home I said, ‘I’m gonna do this,’” she says.

Courtroom art as we know it today emerged from the “Lindbergh Baby” court cases of the 1930s, in which a man named Bruno Richard Hauptmann was tried and convicted for the kidnapping and murder of legendary airman Charles Lindbergh’s child. It was a disruptive media circus of flashbulbs and cameras all vying for a piece of the action at this “trial of the century,” and the American Bar Association ultimately banned cameras entirely. While cameras have begun popping up once again, for a long time courtroom sketches were the only visual recollection of historical or high-profile cases.

The Story Behind the Nine-Year-Old “New Yorker” Cartoon That Defines Our Climate Moment

Tom Toro tells us about his cartoon that’s been shared by everyone from Greta Thunberg to Leo DiCaprioThe first sketch Rosenberg sold was 1980’s “Murder at the Met,” in which Metropolitan Opera violinist Helen Hagnes Mintiks was killed at Lincoln Center. In those days, Rosenberg says, there were sketch artists for every newspaper, magazine, and local and national television news outlet, with as many as 15-20 artists present at a single trial. Noticing that NBC hadn’t conscripted one for the Mintiks case, she offered them her sketches, and they appeared on the news that evening. Rosenberg called her parents in delight, and she has been working in the courtroom as a full-time freelance sketch artist ever since. Her courtroom work is now in the collections of the Museum of Television and Radio in New York and the Museum of the Constitution in Philadelphia, and has appeared not just on NBC, but CBS, ABC and CNN, among countless others.

“For the first probably 10 years, I had a knot in my stomach every time I went to court, which I don’t have anymore, because I was so stressed out,” she says. But she has since mastered the form. She knows what the proceedings will be and how long they’ll take, so she knows how many sketches she’ll have time for. An arraignment like Bannon’s is short, so she’ll have time for one sketch; an hours-long hearing would be three sketches; and a lengthy trial will generate significantly more. But the deadlines don’t change, because outlets need sketches for the five o’clock news and for breaking news. Sketching Bannon was particularly stressful, Rosenberg says, because it was 4:30 when she got out of court.

“I had to finish up my sketch in the hallway because I got kicked out immediately right after the proceeding. So I had to pack up my pastel box and my art supplies, rush into the hallway, and finish up the finishing touches and then get outside and shoot the artwork and email it in. It’s due immediately,” she says. “I don’t have time to go home and finish things, work on anything, touch anything up, whatever it is it is, I have to accept that.” There’s no time to make that neck slimmer or that jaw finer. Sometimes it draws negative attention, as with her renderings of Tom Brady in 2015, but ultimately Rosenberg knows she always has to move on. “Everybody loves to be an art critic,” she says. “I try to just remember that this is all about my own personal journey in trying to be the best artist I can possibly be with the situation as it is, the deadlines.”

Every artist is self-critical to some degree, so this work becomes a simultaneous exercise in speed, skill, patience and letting go. For balance, Rosenberg often retreats to her other gig as a plein air oil painter, and takes as much time as she wants with her canvases. “Sometimes I capture something [in the courtroom] that’s very loose and sometimes I’ll capture some emotion that was a surprise even to me. I keep it simple, I don’t overwork something. Sometimes in paintings I’ll overwork something. I don’t have time to overwork anything in courtroom sketching, so it actually sometimes works in my favor, and sometimes not,” she says.

But as stressful as courtroom art can be — Rosenberg is constantly on call — she hasn’t tired of it yet. “It feels good when somebody needs me and wants me and calls me and says ‘Jane, go now’ and make some money and I’m paid for drawing people,” she says. “I love doing that. It’s just fun.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.