“He assumed the American presidency in what many people regarded as the twilight of freedom. Democratic society was everywhere under assault. Internally from the ravages of unemployment and depression, externally from the ugly menace of totalitarianism… Franklin Roosevelt was an intensely human being, with human faults and human foibles. But these fade into insignificance next to his profound instinct for the massive movements of history…”

-President John F. Kennedy, 1962

There will never be another American like Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The Constitution guarantees there will not. Yes, FDR is the only individual personally to inspire an amendment. (Ratified in 1951, the 22nd Amendment prevents a president from getting elected three times, much less four the way he did.) Which may be why we remember him in a way unique among our commanders in chief.

FDR’s importance is undeniable—rare is the presidential ranking that doesn’t put him third or even second among White House occupants, behind only Abraham Lincoln and sometimes George Washington. But Washington and Lincoln are both mythic figures, larger than life. Indeed, historians often make a point of establishing them as larger than life during their own lives, noting each man was exceptionally tall for his era.

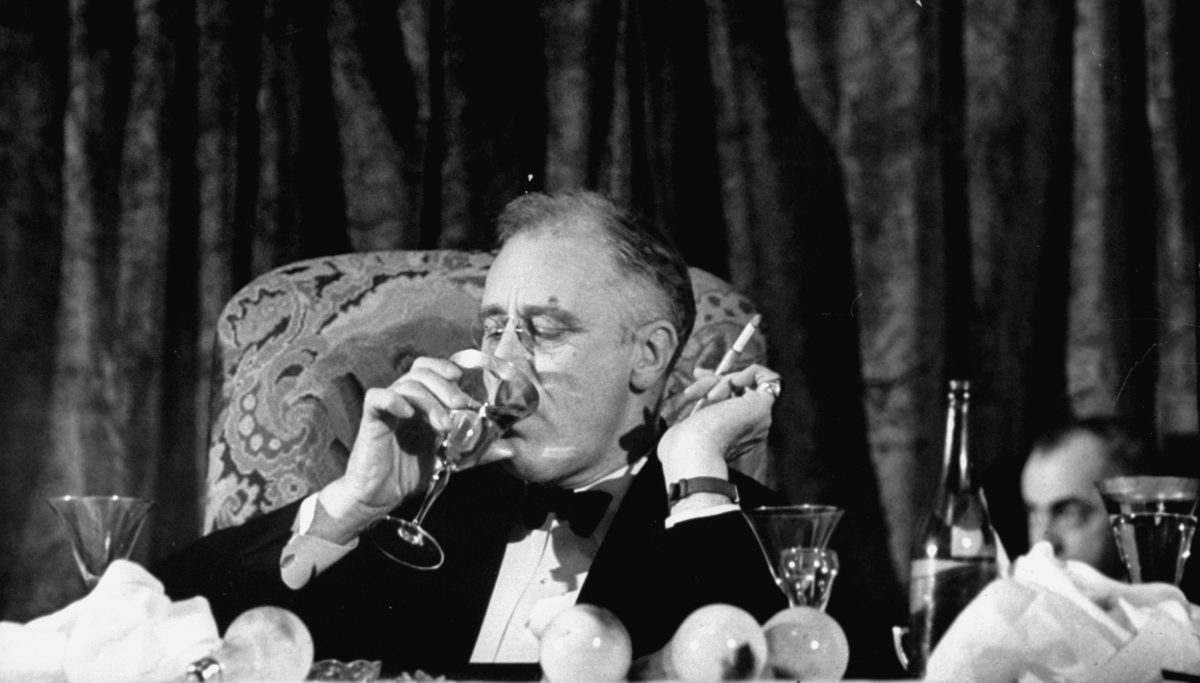

It’s different with Roosevelt. Partly this is because he’s a figure much closer to our times. Though still closer to Lincoln than to us—born on January 30, 1882, Roosevelt grew up during the 19th century. We can actually hear FDR giving his Fireside Chats. We can see him addressing the nation in newsreel footage.

It’s also because Roosevelt was, as Bill Clinton put it, a man who believed in trying things he knew might not work. Clinton said Roosevelt possessed “the self-confidence to abandon a policy that wasn’t working. He believed in experimentation, but he didn’t deny the evidence when an experiment proved unsuccessful. In any highly dynamic time, with new and complex challenges, the President needs an appetite for experimentation and the determination to keep what works and scrap what doesn’t.”

We grow up hearing about how young George Washington bravely confessed to chopping down the cherry tree because he could not tell a lie and Abe gallantly walked miles to give a refund after discovering he overcharged a customer a penny. (Incidentally, there is no evidence either of these events occurred.) Unsurprisingly, we envision them growing into leaders who knew what had to be done and had the courage to do it, no false starts necessary.

Whereas FDR was the guy who kept trying stuff until things sorted themselves out. The result may be that many descriptions of FDR are flattering and a bit insulting simultaneously. Clinton noted that FDR “surrounded himself with brilliant people who knew more about particular subjects than he did.” Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes mused Roosevelt “had a second-class intellect but a first-class temperament.” They’re critiques of FDR’s intelligence—or, at least, recognitions of its limits—but rousing endorsements of FDR’s actual leadership, as a man able to find exceptional people and then let them do their jobs.

Which makes sense: FDR was simultaneously great and incredibly human. This is why he’s not only one of the few presidents we remember—quick, offer a fact about Martin Van Buren, Rutherford B. Hayes, or Benjamin Harrison—but that he inhabits a category all his own, imperfect yet iconic at once.

The Biggest Problems

Donald Trump isn’t afraid to criticize his predecessors. He has hammered Democrats Barack Obama and Bill Clinton, but also found time to go after much of the Bush family. He mocked George Bush Sr.’s “thousand points of lights”: “What the hell is that? Has anyone ever figured that one out?”

Trump even seemed to put Lincoln in his place, declaring in an interview, “You know, a poll just came out that I am the most popular person in the history of the Republican Party. Beating Lincoln. I beat our Honest Abe.” This is questionable: After 9/11, George W. Bush boasted an approval rating of 98% among Republicans—a level Trump has yet to reach—and there doesn’t seem to be any polling data on Lincoln’s popularity among Republican voters during his time in office.

Yet FDR inspired a rare moment of humility. Trump noted during his first cabinet meeting: “Never has there been a president, with few exceptions—case of FDR, he had a major depression to handle—who has passed more legislation and who has done more things than what we’ve done.”

Quite simply, Roosevelt came into office at one of the grimmest moments in American history. The unemployment rate had spiked from roughly 3 percent when Herbert Hoover took office in 1929 to 8.7 percent in 1930 to 24.9 percent in 1933, the year FDR succeeded him. But the problems went beyond the numbers, terrifying though they might have been. RealClearLife has addressed the 1932 Bonus Army Riots, when the U.S. Army attacked WWI veterans in Washington, D.C. Paul Dickson is the co-author of The Bonus Army: An American Epic (written with Thomas B. Allen). He told RCL that despite have having written “60-odd books” and Allen having written dozens himself, this was for “the biggest story we’ve handled.”

For those unfamiliar, the event was even more disturbing than that description suggests. Unemployed and desperate, the veterans had been nonviolently protesting for the early payment of a promised bonus for their service. In return, Dickson said Douglas MacArthur ordered the Army to use tear gas (“much more powerful tear gas than we think of today”) to route them and then had their makeshift village burned with the “equivalent of flamethrowers.” Women and children had been at the camp. Dickson remembered talking to one of those (now long grown) children, who recalled: “We ran for our lives. We thought we were dead.”

People around the nation got to witness newsreel footage of the spectacle. At a time when Americans were already shaken by the economy’s plummet, it seemed like the very nation was on the verge of collapse.

Arguably, the Great Depression was only the second biggest challenge Roosevelt had to face. After the December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States entered World War II. Chuck Thompson—whose books include The 25 Best World War II Sites: European Theater and The 25 Best World War II Sites: Pacific Theater—told RCL it’s vital to remember complete Allied victory was by no means a certainty: “In hindsight, I can’t believe how close we were to letting England fall under Nazi control.”

WWII was savage in a way no conflict has been before or since. Thompson estimates the Soviet Union alone suffered 27 million deaths. Territories under Nazi control experienced unimaginable suffering. An estimated six million Jews were killed. Beyond this, millions of civilians and prisoners of war died, with 70,000 men, women, and children with mental and/or physical handicaps murdered.

Yet there was still another epic challenge to come. As WWII drew to an end, it became increasingly clear that America would soon face a new conflict, one with the Soviet Union that would be waged on every continent except Antarctica. (Actually, scratch that—both superpowers made a point of establishing a presence there, presumably to prevent a penguin gap.)

These are all massive, incredibly complex problems. As FDR confronted them, he raised questions we still struggle with today. These include:

What Worked on the Great Depression? Actually, there’s another question that needs to be answered first: What caused the Great Depression? Monetary policy? Tariffs? A lack of banking regulation/deposit insurance? If more than one, which mattered most? You can get a different answer depending on which economist or which books on the topic you choose to consult. And once you settle on a cause, how do you address it? Do you feel FDR properly addressed it? If he did, which of his approaches do you support? (Again, FDR was a leader willing to experiment.)

Every time the economy seems shaky, we get to revisit this debate.

How Do You Handle the Supreme Court? When the Supreme Court kept striking down New Deal legislation, FDR tried to “pack” it. Since justices hold lifetime appointments, FDR proposed nominating an additional member of the Supreme Court for every member over 70. (Three current justices fit this category.) This idea inspired a great deal of outrage and never came to fruition. But something funny happened: Justice Owen Roberts swung his vote from opposing the New Deal to supporting it. As Smithsonian Magazine noted in 2005: “Never again would the court strike down a New Deal law.” From FDR’s perspective: Battle lost, war won.

Recent decades have found the Supreme Court growing ever more politicized, notably when they awarded the 2000 presidential election to George W. Bush over Al Gore. Things became particularly heated in 2018 with Trump’s nomination of Brett Kavanaugh. Prior to the Senate vote, Philip Bump wrote in the Washington Post that Kavanaugh was poised to owe a lifetime appointment to a “minority-majority.” Bump reasoned that Kavanaugh was nominated by a man who lost the popular vote by nearly three million votes. While Republicans had a majority of the Senate, when actual state populations were factored in they represented only “44 percent of the country.” (Kavanaugh ultimately squeaked through with a 50-48 Senate vote.) While FDR’s proposal is almost certainly not the answer, polls consistently show Americans have lost faith in the Supreme Court over the last 30 years and that plummet is likely to continue.

How Big Should Government Be? FDR signed the Social Security Act into law in 1935. Lyndon Johnson signed amendments to it in 1965 to create Medicare and Medicaid. It is no coincidence that this all occurred under Democratic presidents. In general, GOP reactions to these programs range from seeking potentially steep cuts to desiring radical reform. Indeed, back in 2005, President George W. Bush set out to revolutionize Social Security.

Needless to say, that didn’t happen. Today, Republican Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell speaks of the dangers of America not addressing “the real drivers of the debt by doing anything to adjust those programs to the demographics of America in the future,” saying we need to be “talking about Medicare, Social Security and Medicaid.” But he has declined to offer any specific ideas, recognizing their popularity among Americans. 2017 polling found overwhelming public support for all three—among Republicans, over 80% wanted to maintain or even increase spending. These program have become beloved even among those generally suspicious of the public sector, to the point that former Republican House member Robert Inglis (S.C.) says a constituent once told him: “Keep your government hands off my Medicare.”

What Does It Mean to Be a First Lady? This one’s less high stakes, but still timely. Melania Trump’s spokeswoman has already written an angry op-ed denying that Trump is a “reluctant First Lady.” Which, when you think about it, is insane. First Lady isn’t an elected position. Nor is it an appointed one. It just means you happened to be married to a person at the time they reached the White House. Why should there be any expectations with the position?

For this, Melania can mostly blame Eleanor Roosevelt and the way she redefined the role. A public supporter of both women’s rights and civil rights in general, her female-only press conferences forced publishers to hire women. She proved invaluable to her husband’s administration. When FDR had to face impoverished WWI veterans, Dickson told RCL he took a radically different approach than his predecessor: “As Bonus Army members noted: ‘Hoover sent the army. Roosevelt sent his wife.’”

How Much Should We Respect a President’s Privacy/How Much Does Physical Condition Matter? George Washington was a soldier, horseman, hunter, and apparently even a gifted dancer and bowler. Abraham Lincoln was wrestler and a rail splitter. FDR suffered partial paralysis at 39. (Presumably from polio—there is some debate over the diagnosis.)

FDR’s disability was largely kept a secret from the public. (Though not entirely: TIME reviewed their archives in 2013 and found references to it in some articles from the 1930s, such as noting it “possible for the Governor to walk 100 ft or so with braces and canes;” “Because of the President-elect’s lameness, short ramps will replace steps at the side door of the executive offices leading to the White House;” and “bodyguard Gus Gennerich helped the President into his wheel chair, rolled him the length of the West colonnade to the new White House offices.” The press did a better job for FDR of concealing his longtime affair with Lucy Mercer.)

If this was heavily publicized in FDR’s era, it’s unlikely he would have taken the White House even once, much less four times. Are things different today? With camera phones everywhere, it would be impossible to keep it under wraps. Would we have voted for him? We haven’t elected a disabled president since FDR. (The only nominee who even begins to fit the criteria is WWII vet Bob Dole, who largely lost the use of an arm.) That said, we have now accepted and even celebrate the physical challenges FDR had to overcome, since his wheelchair is immortalized at the Roosevelt Memorial.

Was Enough Done to Help the Jews? All these questions are difficult, but this one is borderline impossible. How could enough have possibly been done, considering that millions of innocent people were murdered? Yet arguments can be made in FDR’s defense. Jews were important members of his inner-circle, notably Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau. He appointed a Jewish justice to the Supreme Court (Felix Frankfurter). More importantly, it can be argued that FDR’s options were initially quite limited—the American public was reluctant to join the struggle against Germany. (Indeed, some Americans still question our involvement, such as former presidential candidate Patrick Buchanan.)

Richard Brightman and Alan J. Lichtman recognize why FDR has received criticism in their 2013 book FDR and the Jews, noting that “his compromises might seem flawed in the light of what later generations have learned about the depth and significance of the Holocaust.” But they also give credit: “Roosevelt reacted more decisively to Nazi crimes against Jews than did any other world leader of his time.”

These questions are all to varying degrees open to debate. This next item is not.

The Indefensible Decision. About 120,000 Japanese Americans were confined to camps during World War II. It was a monstrous action, particularly since so many Japanese Americans served heroically in combat during WWII. (You will not find a more remarkable soldier than Medal of Honor winner Barney Hajiro.)

Beyond this, it was enforced with a bizarre inconsistency. If the military genuinely believed Japanese Americans were a threat, surely they were most dangerous in Hawaii, where they made up a much larger portion of the population than they did in the U.S. as a whole. Yet in Hawaii it was imposed on a much smaller scale, presumably because they were a big enough group that the imprisonment would have decimated the state economy.

For that matter, why didn’t the policy apply to the other members of the Axis? While most German Americans supported the United States and many gave their lives fighting for it, 1939 saw 20,000 people fill Madison Square Garden as the German-American Bund held a rally to show their public support for the Nazis.

In summary: The internment of Japanese Americans is and shall always be a massive stain on FDR and his administration.

Yet it doesn’t destroy FDR’s legacy completely. (As can be argued Woodrow Wilson’s deep racism decimates his—taking office in 1913, he strove to turn the clock back to a more bigoted time by working to segregate federal offices.) FDR made an unforgivable mistake, but we shouldn’t ignore how much he got right.

Three for Three

FDR faced the Great Depression, World War II, and the very beginnings of the Cold War. He died at 63 of a massive cerebral hemorrhage on April 12, 1945. (His last words were: “I have a terrific pain in the back of my head.”) By then, the U.S. unemployment rate had dropped to under two percent. Germany and Japan surrendered before the year was out. And the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991.

Did he do everything right or deserve total credit for these triumphs? Absolutely not. But he got enough things correct. And the public showed their appreciation.

Winner of Winners

Barring a very unexpected constitutional amendment, FDR will be the only person to win more than two presidential elections. Even if somehow someone equals that feat, good luck matching FDR’s margins. Each of his four victories saw him collect at least 53.4% of the popular vote and 432 electoral votes, with highs of 60.8% and 523 (1936).

Having reached the presidency while losing the popular vote, it’s no surprise Trump falls short of these totals (304 electoral votes/46.1%). But they best Barack Obama too. Obama twice won handily, yet his 52.9%/365 in 2008 and 51.1%/332 in 2012 can’t approach FDR.

If a president’s self-picked successor is viewed as part of his legacy, then FDR acquits himself nicely here as well. Harry S. Truman was treated dismissively by much of the press, culminating in the notorious “DEWEY DEFEATS TRUMAN” headline. It’s often forgotten that Truman’s victory was more of a knockout than a nail-biter with 49.6% of the popular total and 303 Electoral votes—poor Dewey finished with 45.1% and 189. Truman’s popularity fell in his second term, but time’s been kind: Presidential historians consistently rank him fifth or sixth. It should be noted this is one area where FDR tops Lincoln, as Abe’s VP and successor Andrew Johnson proved a disaster from a drunken inauguration through to the day he left office.

FDR also gets bonus points for accomplishing everything so cheerfully. Understand: His relentlessly upbeat attitude was an act of extraordinary will, as he spent much of his life in great pain. (FDR may have been alluding to his ability to conceal discomfort when he told Orson Welles, “You and I are the two best actors in America.”) Which is why he, like Lincoln, is the rare great leader who actually seems fun. As Winston Churchill quipped, “Meeting Franklin Roosevelt was like opening your first bottle of champagne; knowing him was like drinking it.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.