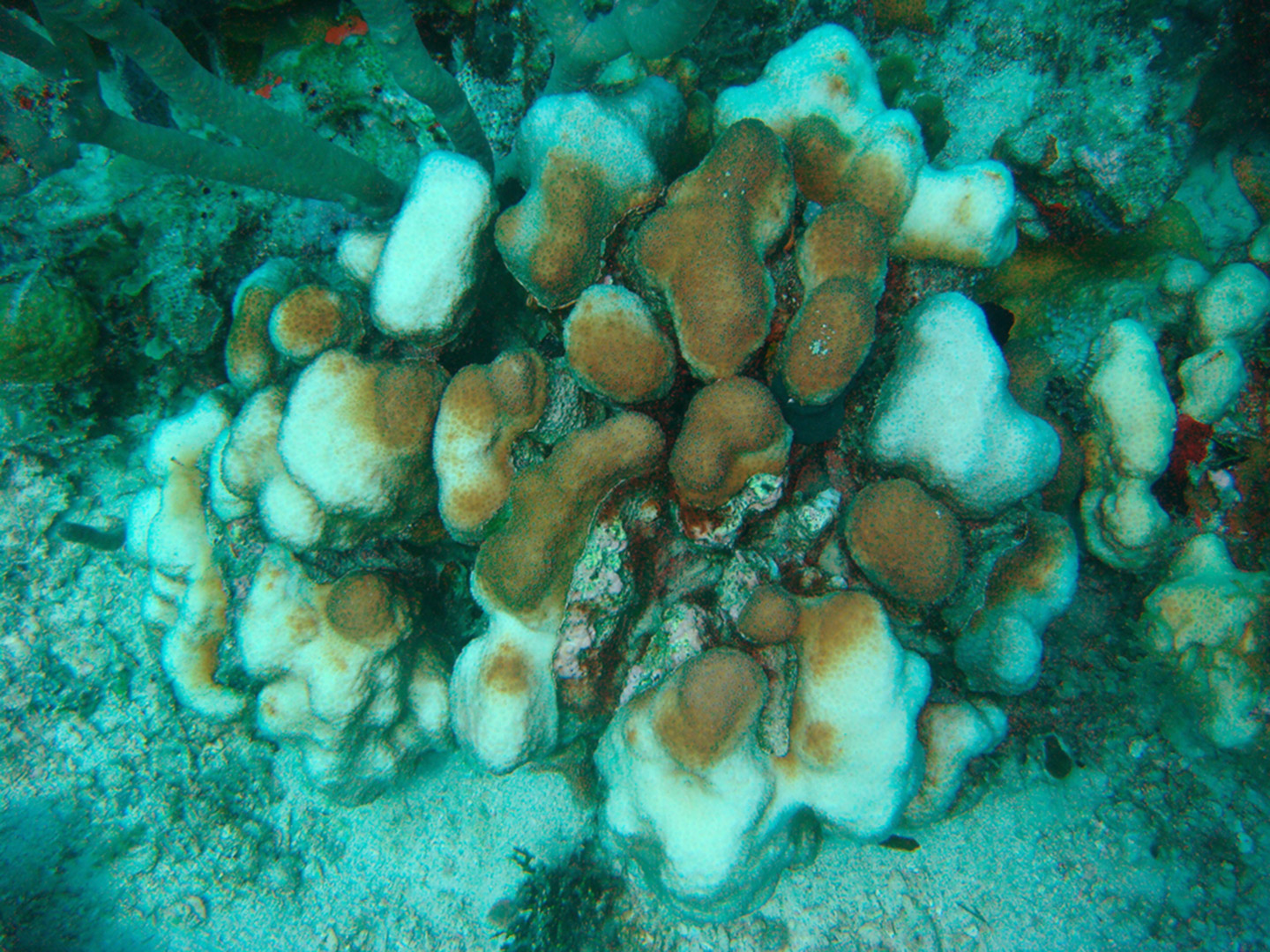

Ravaged by rising global sea temperatures and environmental stress from pollution, the coral reefs of the world are teetering on the edge of extinction.

And saving the reefs isn’t just for the fishes—although the damage to all the sea life that depends on those ecosystems would be catastrophic. The Nature Conservancy estimates that coral reefs benefit approximately 500 million people worldwide on a daily basis by providing them with food and livelihoods, and protecting them from environmental threats like massive waves, storms, and floods. Reef-related goods and services generate a staggering $300 billion annually for local economies. The numbers make it clear: As the ocean continues to absorb CO2 from the atmosphere, becoming more acidic in the process and triggering deadly bleaching events, the stakes are massive.

That’s why scientists in the Caribbean are in a race against time to use cutting-edge methods—slashing coral into pieces, growing it in labs, and re-planting it on dying reefs—to stave off extinction.

The scale of their quest is daunting. News emerged earlier this year that the Great Barrier Reef can no longer be salvaged in its current form. Warmer waters and a 2015-16 El Niño killed more than 40 percent of the coral at Dongsha Atoll in the South China Sea. That number rose to catastrophic heights in Japan, where the government’s environment ministry reported in January of this year that more than 70 percent of the country’s largest coral reef has been decimated.

“The reefs today are completely different” than in years past, Dr. Luis Solorzano, executive director of the Caribbean Division of The Nature Conservancy told RealClearLife.

“Generation after generation, the standard of what is beauty and nature is less and less,” Solorzano added, noting that even his own son can’t conceptualize the stunning vision once boasted by area reefs. “We have to stop that now.”

The situation in the Caribbean is especially critical, where scientists estimate between 50 and 80 percent of living coral cover has disappeared in the last three decades alone.

“We have transformed so much of the planet, so fast, that we have accelerated that background rate of extinction, and orders of magnitude, so we are reducing the biodiversity of the planet,” Solorzano said. “We know that (corals) can adapt…we don’t know if they’re going to have time to.”

It isn’t just the changing climate that is threatening the reefs, either. Overfishing, pollution, and coastal development threaten both existing reefs and restoration efforts. Solorzano explained that effort has to occur on cultural, societal, and governmental levels in order for restorations to be effective.

“Obviously it cannot be done only by scientists or by conservationists. We need the private sector, and governments maintaining commitments like the Paris Climate Agreement…it’s complex,” Solorzano admitted.

It’s also a work in progress. The Nature Conservancy is a part of the Caribbean Challenge Initiative, a coalition of governments, companies, and partners working in multiple ways to triple marine protected area coverage in the region. In addition to microfragmentation, which is the cutting, growing and replanting of corals, the conservancy and its partners are also working on facilitated sexual reproduction. That technique is used to produce large quantities of genetically diverse coral embryos at the same time, then growing them in protected nurseries until they’re ready to be planted.

Additionally, the conservancy works with the Environmental Protection Agency, headed by Scott Pruitt under the direction of President Trump. While the agency has distanced itself in recent months from prioritizing climate change battling initiatives, the agency has and will continue, to do important work in preserving coral reef systems, an EPA spokesperson, who asked to remain anonymous, told RCL in an email.

“The EPA, through the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force, has worked in partnership with its members as well as with nongovernmental organizations, such as The Nature Conservancy, and commercial interests to support the design and implementation of management, education, monitoring, research and restoration efforts to conserve coral reef ecosystems,” the representative said by email. “Additionally, EPA’s Region 2 Office facilitates an inter-agency effort to protect coral reefs in the Caribbean Region.”

President Trump’s 2018 budget slashed the agency’s budget from $8.2 billion to $5.7 billion — the lowest its been in 40 years, adjusted for inflation — but the EPA spokesperson noted that $193 million would still be included to support work in surface water protection and wetlands programs.

Solorzano notes that the key to saving the world’s reefs lies in multi-level collaborations, and stresses that there’s no such thing as a “super coral” that scientists can develop to perfectly adapt to a warmer, more acidic environment. But he holds out hope for the important work currently be done, and what will continue to be carried out by the next generation.

“The next generation, you have different values,” he said. “My son doesn’t care about having a fancy car, he cares about people and the planet.

“That right there is the opportunity for a new industry. If we really learn how to do this: arborists and landscapers today, coast and reef builders tomorrow.”

For visual insight into how the conservancy is creating and working within coral nurseries to help save endangered coral in the Caribbean, watch the video below.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.