I first met Dani Cessna a few years back at Sequoia National park on a shoot for the Travel Channel. I was hosting a show and she was the park ranger giving me insight into the magnificence of some of the tallest and oldest trees in the world. These majestic giants can live more than 3,000 years and grow from a seed so tiny you could mistake it for one from a simple wildflower. As Dani held the tiny germ in her palm for me to marvel at, I remember thinking she had a dreamy job and a whimsical life full of scented pine needles swaying in the breeze and wildlife shadowing her every step like Snow White. Her office was the great outdoors and that in itself is the fantasy of the Benjamin Button in my soul who longs for wide open spaces on a daily basis.

Reading Dani’s answers in this story makes me respect her path and perspective all the more. Her words ring with passion, commitment and effervescence. She’s the readily conscious interpretation ranger who keeps our wild places wild and the delicate humans who have become unfamiliar with true wilderness safe from their own transgressions. She is essentially the buffer between the two-legged and the four-legged creatures that wish to luxuriate in the same commanding undomesticated spaces offered to us by the park systems.

She has mastered the philosophy that a hunter-gatherer lifestyle is not mutually exclusive to a lifestyle dedicated to conservation practices. She describes this balance beautifully below as well as painting pictures of her life that are both envy-inducing and hilarious. The visual of Dani, a petite blonde, chasing a bear from a campground with fireworks and paintballs resonates like a fabulous SNL skit.

Her passion for the great wide open and its inhabitants echoes in every sentence she shares. From educating the public about co-existing with apex predators like bears and sharks in the habitats where they make their home—a skill rather buried in todays city-centric lifestyles—to teaching urban dwellers the art of a successful campfire, Dani has dedicated herself to every aspect of protecting one of the greatest gifts this country offers, public lands.

The history of women serving as rangers in the national park system dates back to 1918, when 18-year-old Claire Marie Hodges became the first female ranger at Yosemite National Park. Her position came about as a stroke of good fortune due to a shortage of young men preoccupied with the demands of WWI, but also through the innovative mindset of a park superintendent who encouraged her to apply. For the next 30 years, Hodges was the only official female park ranger in the system.

Dani is as much a steward of the flora and fauna of our nation’s wildest corners as she is of the vital wild spark whose embers flicker in our collective consciousness like stars on a moonless night. She is there to guide us when our hearts long for the peace that only the cool green of the forest and the deep blue of the ocean can offer.

When we heed our own call of the wild, we allow ourselves the freedom to see pure inspiration in the beauty of nature. The symmetrical swirl of a seashell that inspired Antoni Gaudí to creative greatness in designing the spiral staircases of the Sagrada Familia. The captivating black-and-white landscapes captured by the lens of Ansel Adams. Even the bizarre becomes wonderful when viewed through the lens of wonder. In Dani’s own words, “Even strange gelatinous blobs that wash up at low tide bring me joy, because they’re mysteries I can puzzle out. I’m always looking for adventure even in the mundane, and because of that I rarely have a bad day.”

——————————————

KP: Passion is a powerful driving force for people. How did yours develop and mold who you are and what you do?

Dani Cessna: Some of my earliest memories are of walking through the Pennsylvania woods only steps behind my dad (sometimes many steps behind him. He still out-hikes me to this day). I grew up in a big hunting and fishing family. We rarely bought meat from the grocery store, and I was skinning game by the time I was in elementary school. My family also did wildlife rehabilitation for the state of Pennsylvania, so I spent much of my youth feeding baby birds off of popsicle sticks, bottle-feeding whitetail deer fawns, and carrying baby flying squirrels around in my sports bra. It never occurred to me that it would appear odd for a hunting family to also be so dedicated to wildlife rehab.

But as I grew older, I learned that others saw this to be a contradiction. To this day, I argue it isn’t. Both of these things, hunting and wildlife rehab, instilled in me an utter passion for wildlife. One activity is an active participation in the cycle of life, a natural and responsible way to obtain your food, and to have a complete understanding of where your food comes from. Wildlife rehab, on the other hand, is rescuing animals that are victim to human development—the unnatural obstacles humans have brought to the natural world. So many of the baby animals we raised and released into the wild came into our care because they lost their mothers to a car, a domestic cat, a tree felled for development, or some other unnatural fate.

So for me, it was as natural to be a passionate hunter, a part of the natural cycle, as it was to be a passionate wildlife rehabber. Still today, as a dedicated park ranger who believes in preservation of our public lands, you’ll find me in my free time backpacking into the wilderness of Colorado with the hopes of killing an elk. If I’m lucky, I pack out every pound of meat on my back across a monstrous canyon. Nothing tastes better than a meal you had to carry out of the woods yourself.

KP: Are there any female predecessors in your field who have inspired you?

DC: Denise Robertson, the superintendent at Chaco Culture National Historical Park and Aztec Ruins National Monument in New Mexico, and Stephanie Sutton, North District Resource Education Supervisor at Great Smoky Mountains National Park in Tennessee. Steph and Denise hired me into my first permanent position as a park guide, and they’re still the ones I turn to for guidance. Denise supervised me when she was a District Interpretation Supervisor (the equivalent of my position now). I remember watching her and thinking I could never be as badass as she is. And now that she’s a superintendent and I’m the district supervisor, I look at her and think the same.

Both these ladies taught me my voice and my ideas deserve to be heard, no matter who else is in the room. They instilled in me a need to innovate and to push the envelope, and taught me it’s alright to fail, as long as I’m willing to regroup and try again. As a supervisor, I am my staff’s biggest supporter. My attitudes, my habits, and priorities directly impact their success and wellbeing. The team I’ve built is my greatest success as a ranger, and I wouldn’t have been able to do it without the example Denise and Steph set for me years ago.

KP: What is the process of becoming a park ranger, what has your career trajectory been in terms of where you have worked and any specifications you may have gravitated towards?

DC: I fell into the National Park Service on accident. I started out my undergrad at Slippery Rock University in Pennsylvania as an English Education major, because I have always enjoyed reading and writing, and thought being a teacher would fulfill that interest. My first semester, I found myself glazed over in a Composition and Rhetoric class, and knew I had to find something else.

My second semester, I had picked an environmental geology class as an elective, and we went out to study the hydrology of the local watershed. I’ll never forget it because it was an unusually warm day in early spring, and I could smell the melting snow, and I was hooked. I changed my major to environmental studies with hopes of more classes outside. I ended up in a wildlife management internship at the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, where I was the only woman in the wildlife division. I trapped and shot invasive, feral pigs. I trapped and relocated black bears as part of an elk calf mortality study. I hiked the Appalachian Trail along the North Carolina-Tennessee border, packing cases of sardines for miles and miles for bait station surveys. (We would hang sardines every half mile, and then check back a couple days later to see if a bear had found them. It was supposed to be a basic bear density study, but I often wondered the data implications when one bear would catch on and hit ever sardine can on the trail. Black bears are brilliant that way.) I was in love with the National Park Service after that summer. I knew I had found my calling.

I went from Tennessee to Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks in California, where I worked another season in black bear management. I would run through campgrounds at night, screeching at bears and shooting them with paintball guns. The goal of bear management is to keep bears wild, so when a black bear would start to find food in campgrounds and picnic areas, we would apply a negative stimulus (like yelling, shooting paintballs, or setting off firecrackers) to cause the bear to associate developed areas with something negative. (We call this aversive conditioning.) This only really works though if the food rewards are eliminated, because often a campground or picnic area provides such a significant food reward for a bear, they find it worth the trouble of getting chased by a twenty-something girl with a high-pitched voice and a bouncing ponytail.

So really, the first and most successful tool in bear management is education. If people learn to properly store their food and scented items in bear country, it greatly minimizes the risk of a black bear becoming food conditioned and/or habituated to people. This is what led me to the next step in my career. So much of bear management was reactive. I was working with park visitors most often over a ravaged cooler or just after a bear took off with their picnic lunch (it’s not just Yogi who does this), or in the middle of a traffic jam where visitors were crowding a bear who was grazing in a meadow, minding his own business.

My point is, my interactions with the public were always after mistakes were made. Out of concern for keeping the bears wild, I was yelling at folks, correcting them, sometime calling law enforcement to ticket them. I don’t doubt I negatively impacted a few vacations. I’m a people person. I realized that bear management was more so people management than anything, and if I wanted to make a difference, I needed to get to the people before they were out making mistakes with the wildlife. So I became an interpretation ranger, where my job was to educate and connect visitors to the resources of our national parks. Still to this day, I help folks answer the “why care?” and “how do I care?” questions. Why should I care about the bears? How do I care for the bears? And after that, I became a supervisor, where my staff and I organized and led ranger led walks and talks under the largest trees in the world. And when I was itching for new horizons, I applied to Cape Cod National Seashore, where I becme a District Interpretation Supervisor. I’ve left the bears behind, but I would never move on to another park without a new wildlife love. Here, it’s all about the white sharks.

KP: What are the intricacies of being a woman in this profession?

DC: Now that I’ve been with the NPS a decade, I reflect on this particular aspect a lot more than I used to. First of all, I’d like to say that I’ve been very lucky and have overall experienced nothing but very supportive supervisors, coworkers and staff during my time in the NPS. In the earlier days, I rarely thought twice about being a woman park ranger. Recent coverage of events in other national parks has made me realize that not all women with this agency or in other land management agencies have been as lucky as I have. It’s made me much more aware of the tiny cultural aspects that allow these bigger problems of harassment and discrimination to exist.

There was a time where I was a woman who laughed a lot of things off, shrugged my shoulders and said “that’s no big deal” when one of those border-line inappropriate comments was made. Part of my change in perspective is because I’m growing older, the other part of it is I’m realizing that these little things contribute to the bigger cultural issue, and I can no longer shrug them off. Every day I work hard to create a culture of inclusivity in my operation. Even above my dedication to protecting our public lands is my goal of making the park service a more diverse, inclusive agency, and the only way to do that is by speaking up every single time I see behavior that contradicts that mission. There’s been a couple instances where this has required me to muster major courage, but it’s absolutely necessary.

KP: What is an average day like for you? What is a more demanding day like for you?

DC: On a regular day, I might head to the beach to coach a sharks and seals program for one of my seasonal rangers. Or I might film a video on how to have a safe and successful beach fire. As a supervisor, I have my fair share of administrative work that seems far less glamorous than other aspects of park “rangering.” But I take pride in hiring outstanding employees and building a team that reaches thousands of visitors at Cape Cod National Seashore. My team is passionate about the National Park Service mission, and the most fulfilling aspect of my job is supporting them as they connect visitors to our park, and supporting them as they grow and thrive as rangers.

On a demanding day, we might have 2,000 people show up to the visitor center for an eclipse program that we expected would only have around 200 (only 60% percent of the eclipse was visible on Cape, but somehow it still went viral). That’s the kind of day that puts the positivity and resiliency of my team to the test—we did an awesome job considering it looked like the apocalypse on our front lawn, and everyone seemed very pleased with the experience!

KP: What are some of the more unusual, interesting, odd, funny, unnerving or otherwise unexpected things that have fallen under your job description in the course of your career?

DC: I think the more unnerving side of this job can be when accidents happen. All of my career has been working with visitors as they recreate and learn about our national parks and wild spaces, which most of the time ends very happily. But there are dangers in our wild spaces. I’ve worked on search and rescues. I’m a trained peer supporter for Critical Incident Stress Management, which means when one our NPS staff has to respond to a visitor fatality, I’m their support when they need to debrief after the incident. Our park is still grappling with a recent fatality due to a white shark bite. I’ve spent so much time in this job educating the community and our visitors about how amazing white sharks are. But now we have to take into account this new perception, this new reality for people. The risks of recreating in white shark habitat haven’t changed, but everything feels different now that we’ve had a fatality (the first on Cape since 1932). White sharks are still amazing, but I think the risks are more real to people now.

I think of it like any national park wildlife, like grizzlies in Yellowstone or alligators in the Everglades. We still enjoy these spaces, but we also have to be educated about what it means to recreate in the habitat of large predators. And then we make choices about our activities based on our understanding. White sharks are a natural part of our ecosystem, but they are a relatively new reality to our community due to the rebounding of the seal population after the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972. The return of the seals has brought the sharks closer to shore to utilize this natural food source. Many folks here grew up never thinking twice about going into the water, but that has changed. Because of this, I think my team and I have to be extra diligent about reaching our park visitors. There’s so much misinformation out there about sharks. We want people to care about them, and understand that while there are risks, white sharks don’t want to attack people. They’re here for the seals. We’re striving to strike a balance in our messaging so that people aren’t terrified, but they’re also not unaware. It’s a big job in a community where sharks are the hot button issue. We’ve been collaborating with the local community leaders, the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries, and the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy to make sure that the entire Cape is educated on white shark safety, the importance of white shark research, and the role of sharks in our marine environment.

KP: What are some of the insights into the natural world and our human footprint on it that you have garnered from being a park ranger?

DC: I think our biggest mistake as humans is forgetting that we’re just as much a part of nature as any wildlife. Separating ourselves so completely from the natural world has more of an impact on our wellbeing that we realize. Listen to the stories we tell. All of them are tied to landscapes in some way. Having a sense of place is essential to our lives. I don’t expect people to leave the city and disappear into the wild. But I do think that people need to find a green space if they don’t have one. Maybe it’s an old lone oak in a tiny city park, or a bench along the river that runs through downtown. Find somewhere you can go to center yourself, find peace, and remember that we are part of something much bigger. Part of a natural cycle that is tried and true. In the chaos of modern life, nature is a constant we can depend on, and we need to see the value in caring for it. These places nurture the spirit.

KP: Can you describe one of your favorite experiences in nature using the five senses?

DC: When I worked bear management, we would often trap and chemically immobilize problem bears for research, tagging, and to install a radio telemetry collar on them for monitoring. One of my favorite experiences ever was monitoring the respirations of a drugged black bear. I would put my hand on his back and count each breath. I’ll never forget rise and fall of those breaths under my hand, and the deep, rumbly nature of them. It made my breathing seem so shallow and inconsequential compared to his. But it was familiar. My life and the bear’s, so different, but more similar than I could have imagined. I’d lean in and breath in his scent—ferns, and dirt, and other spicy unknowable things. A smell so wild and satisfying. It was a moment that opened up a world for me.

KP: Clearly, your profession begs the question…do you have a favorite national park, state park, BLM land?

DC: This is always such a tough question because my answer is always changing. I once thought I’d always be a mountain girl, whether it be the old mountains of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, or the jagged peaks of the Sierra Nevada in Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. Now that I have the ocean here at Cape Cod National Seashore, it’s hard for me to imagine life without the salt air and the perpetual layer of sand in my car. These places are all so special in different ways, but the one thing they have in common is the way I carry them with me wherever I go. The different landscapes of my life have really shaped who I am, literally broadened my horizons. Now my love might be with the ocean, but five years from now I might have discovered somewhere new and wild.

KP: What are some of the fun facts about our natural lands that people may not realize?

DC: There are 417 units in the National Park Service. I tend to be more of a naturalist, but not all these units are about nature. They’re about our stories, and our values as human beings. Whether you love history, nature, culture, science, or any combination thereof, you can find a place that inspires you, that speaks to you, in our public lands. Maybe it’s at the rim of the Grand Canyon in Arizona. Or the Liberty Bell in Philadelphia. Maybe it’s on the battlefields of Gettysburg in Pennsylvania, or at Stonewall National Historical Site in New York. Maybe it’s the condors of Pinnacles National Park, or the volcanoes of Hawaii. Find your park.

KP: Everyone has a message they put out into the world through their words, actions and lifestyle. What is yours?

DC: I think my main message is to find magic in the everyday. Partly due to lucky brain chemistry I’m sure, but also partly because I find utter glee in the sight of a blue heron gliding across the salt marsh like a modern-day pterodactyl. Or in the scurry of a gray squirrel up a tree trunk. I love the smell of rainy days, and the sound of the wind in the trees. Even strange gelatinous blobs that wash up at low tide bring me joy, because they’re mysteries I can puzzle out. I’m always looking for adventure even in the mundane, and because of that I rarely have a bad day.

KP: What future life goals do you have for the next five years? Any big bucket list items, travels, career goals, etc.?

DC: Most of my bucket list items involve wildlife in some way. I want to dive with white sharks off of Guadalupe Island. There’s an elephant sanctuary in northern Thailand I want to visit. I want to climb the mountains in Brazil, and see the grizzlies feed on salmon in Alaska.

Also, I’m always working on new writing projects in my free time, and I devour any book I can get my hands on. So really, I can boil down my life goals to exploring and creating. As long as I’m doing both of those, I’m happy wherever life takes me.

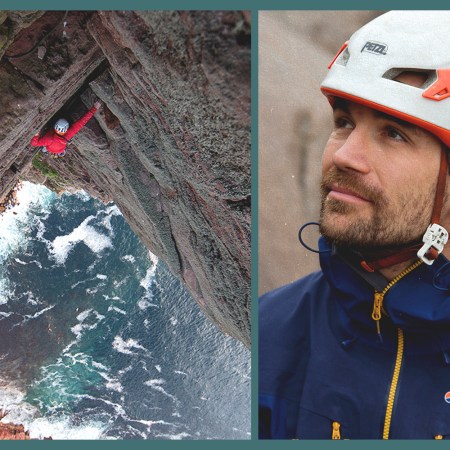

Never one to sit still, Kinga Philipps has tested herself for the past decade by traveling the globe, rappelling, caving, scuba diving, jumping out of airplanes and diving with the sharks as a writer, producer and on-camera host. In her rare bits of free time, Kinga explores her singular fascination with sharks followed by a love for the beach, surfing, motorcycles, cars, charity work, travel, food and action sports.

This article was featured in the InsideHook newsletter. Sign up now.