We’ve grown accustomed to the politicization of sports: national anthem protests, cancelled White House visits, coaches and players making pronouncements on matters of the day—and a president more than willing to weigh in. Though separating sports from politics seems harder than ever, it’s worth keeping today’s controversies in perspective. Like most news stories, they’re topical, intense—and temporary.

If you want an idea of what a really political sporting event looked like, one that really did seem to carry the weight of the world, then consider a contest marking its 80th anniversary today: the heavyweight title fight between champion Joe Louis, 24, and challenger Max Schmeling of Germany, 32, in Yankee Stadium, on June 22, 1938. No sporting event has ever had more riding on the outcome, and no two athletes have ever been so freighted with symbolism.

The fight took place under the shadow of an approaching world war, with Adolf Hitler’s Germany growing more brutal by the month in its persecution of Jews and other scorned groups at home, and more brazen in its territorial incursions in Western Europe. It took place in an America still reeling from the Great Depression, a country still short on work and, if you were black, short, too, on the fundamental liberties protecting life and limb: the NAACP was still hanging a banner outside its New York offices reading, “A man was lynched yesterday.” It was in this environment that Schmeling, a national hero in Germany whose triumphs were touted by the Nazis as proof of Aryan supremacy, and Louis, an American who had become a folk hero to blacks, met in the Yankee Stadium ring on a cool June night. An estimated 60 million people—nearly half the nation’s population—tuned in to the radio broadcast, the largest audience up until then to hear any program, even FDR’s fireside chats. In Germany, millions listened in the early morning hours. Could a black man from democratic America defeat an Aryan representative of Hitler’s Reich in a contest of will, skill, and courage, with the world watching? Millions craved—and feared—the answer.

*****

As if any more suspense were needed, the big fight also carried the expectations of a sequel—because Louis and Schmeling had met once before, two years earlier, on June 19, 1936, also in Yankee Stadium. Louis, just 22 and undefeated, was the phenom of the heavyweight division, rattling off devastating victories on his path to the top and earning the nickname the Brown Bomber. Though only one black man had ever been permitted to fight for the heavyweight championship—the then-notorious but now-celebrated (and pardoned) Jack Johnson—it seemed inevitable that Louis would get a shot, and win. In the meantime, he would stay busy with Schmeling, a 30-year-old former heavyweight champion trying to resurrect his career but given little chance against Louis.

Schmeling had always been a thinking fighter, though—sometimes to a fault—and he analyzed Louis’s flaws on film, especially his habit of dropping his left hand after jabbing, leaving himself open to a right, which happened to be Schmeling’s best punch. Landing that right with the persistence of a judgment, Schmeling took control of the bout and produced one of boxing’s great upsets, knocking Louis out in the 12th round.

It was the highlight of Schmeling’s career; it would have been the highlight of anyone’s. Those gathering in Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels’s living room exulted—especially Schmeling’s wife, actress Anny Ondra, a special guest for the evening. Germany planned a hero’s welcome, sending its famous airship, the Hindenburg, to fly Schmeling home. He was greeted by adoring crowds in Frankfurt and then in Berlin, where he had dinner with Goebbels and watched a film of the fight with Hitler. The Führer decreed that the film—with an added voice-over narration celebrating Aryan virtues and denigrating Louis—be shown around Germany with the title Schmeling’s Victory: A German Victory.

Black Americans were devastated. Langston Hughes described walking down Seventh Avenue in Harlem and seeing “grown men weeping like children, and women sitting on the curbs with their heads in their hands.” In Cincinnati, 19-year-old Lena Horne, performing with Noble Sissle’s band at the Moonlite Gardens, broke down when the radio revealed Louis’s defeat. Her mother chided her for this unprofessionalism. “You don’t even know the man,” she told her daughter. “I don’t care!” Horne retorted. “He belongs to all of us.”

Schmeling’s win should have put him in line for a shot at heavyweight champion Jim Braddock, but politics intervened. Boxing’s power brokers in New York did not want the title to become the property of Nazi Germany, and through some complicated maneuvering, they arranged for Louis to fight Braddock for the title instead. On June 22, 1937, Louis knocked Braddock out in the eighth round to become heavyweight champion, but his win seemed more like a preliminary. “I don’t want nobody to call me champ until I beat that Schmeling,” he told reporters, and soon a rematch was made. What Louis and Schmeling saw as an athletic competition, however, took on the trappings of a global event with significance far beyond boxing. The bout’s centrality was captured in variations of a cartoon showing a globe with a human face, looking down at the Yankee Stadium ring where Louis and Schmeling would clash, anxious to learn the result.

*****

Though he distanced himself from Hitler whenever he was in the United States, Schmeling’s public identification with Nazism grew ever closer, whatever his private feelings might have been. He was regularly celebrated in the German press, including the magazine of the SS and Der Angriff, Goebbels’s Nazi Party newspaper. He attended Nazi Party rallies at Nuremberg and participated in public celebrations of the Führer’s birthday. He encouraged Germans to vote ja in the phony referendum that Hitler set up to ratify the Anschluss—the Nazi annexation of Austria—and was photographed doing so himself. He attended preview screenings of Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia documentary.

Louis, meanwhile, bore a national burden that few would have imagined. His stature in black culture had reached new dimensions, as reflected in black popular music. At least 43 songs about Louis have been documented or recovered, more tributes by far than any other athlete has ever inspired. As adored as Louis was in black America, though, the Schmeling fight hovered over his future. Blacks agonized about whether he would prove equal to the test, as did American Jews.

When Jack Johnson, Louis’s only black predecessor as champion, fought white challengers, black and white Americans took sides with their race. But now, in 1938, many non-Jewish white Americans rallied to Louis’s side, seeing him as America’s standard-bearer against Hitler’s favorite fighter. It would prove the turning point of Louis’s career, when he became a figure deeply tied to the country: a symbol of American democracy. That he was the representative of a people that had been denied the full benefits of democracy made the identification more haunting and profound. Thus did Joe Louis become a vital figure in the history of American race relations—and thus did boxing, so often derided for its tribalism, become, for a moment, an instrument of national unity.

Opinions on the upcoming fight varied, but even those who favored Louis underestimated his competitive fire. They didn’t see the rage he felt at his 1936 defeat, his anger at Schmeling’s later accusations that Louis had deliberately fouled him, and his resentment, to the extent that he followed the news, of the Nazis and their “master race” talk. How wholeheartedly Schmeling endorsed the Nazis, Louis didn’t know and didn’t care; he only knew that he wanted to win more than he’d ever wanted anything.

On the day before the fight, Louis sat at his training camp in Pompton Lakes, New Jersey, with the young sportswriter Jimmy Cannon, who had just filed his prefight column.

“You make a pick?” Louis asked.

“Yes.”

“Knockout?”

“Six rounds.”

“No,” Louis said, “One.”

Cannon stared. Then Louis held up a finger.

“It go one.”

*****

About 70,000 fans crowded into Yankee Stadium on a cool summer night, paying $1,015,012, the first million-dollar gate since the Jack Dempsey–Gene Tunney Long Count fight in 1927. In cities and towns across America, friends and neighbors gathered around radios. Movie houses stopped films so that the fight could be patched in over the intercom. Even Eleanor Roosevelt, no student of pugilism, consented to listen—she couldn’t ignore it.

At 10 p.m., the bell rang, and Louis advanced on Schmeling with cold purpose. Everything about his movements, from the way he held his hands to the whipsaw power of his punches, was a world away from 1936. Wearing his customary blank expression, he walked Schmeling into smaller and smaller parts of the ring.

Schmeling held his left out, trying to keep a distance between himself and Louis, waiting for his opening. Then Louis seemed to leap at the German, firing punches—every one thrown with knockout power. The punches were short and precise, a calculated, controlled ferocity.

Schmeling had taken several stiff jabs to the face when he backed along the ropes, still holding out his left. Louis broke through it, landing a clean right to his jaw. Schmeling’s knees buckled, and he almost went down. Louis let go with a fusillade as Schmeling reached out to grasp the ropes with his right hand—but the hand would have been better used protecting himself, especially in the belly, where Louis pounded him. Louis fired a savage right to the body, and Schmeling, turning his torso slightly in defense, absorbed it in his left side. The punch shattered Schmeling’s third lumbar vertebra and drove it into his kidney. He screamed, the sound echoing out into the night air and striking fear into some at ringside. Louis, his mind churning, thought that it was a woman in the crowd. “How’s that, Mr. Super-Race?” he thought.

Schmeling’s left knee bent to the canvas but then straightened up. It was close enough that the referee, Arthur Donovan, stepped in to start a count. Seeing that Schmeling was already upright, Donovan waved Louis in. Louis landed a clean right to Schmeling’s jaw—the punch could have come out of a boxing manual—and the German tumbled down. He was up quickly, just in time to absorb another volley of punches. Everything Louis threw landed—jabs, left hooks to the body, rights to the head. The German started to the canvas again, with both gloves touching the mat, then straightened himself up. Again, Donovan moved in to count, then motioned Louis back in.

One of boxing’s great referees, Donovan had never seen an assault like this in the ring, and he wanted to give Schmeling every chance while also protecting him from serious injury. In Schmeling’s corner, too, the urge to rescue Max was mounting. Everything was happening too fast. Across the Atlantic, over static-ridden radio connections, Germans listened in silence and confusion.

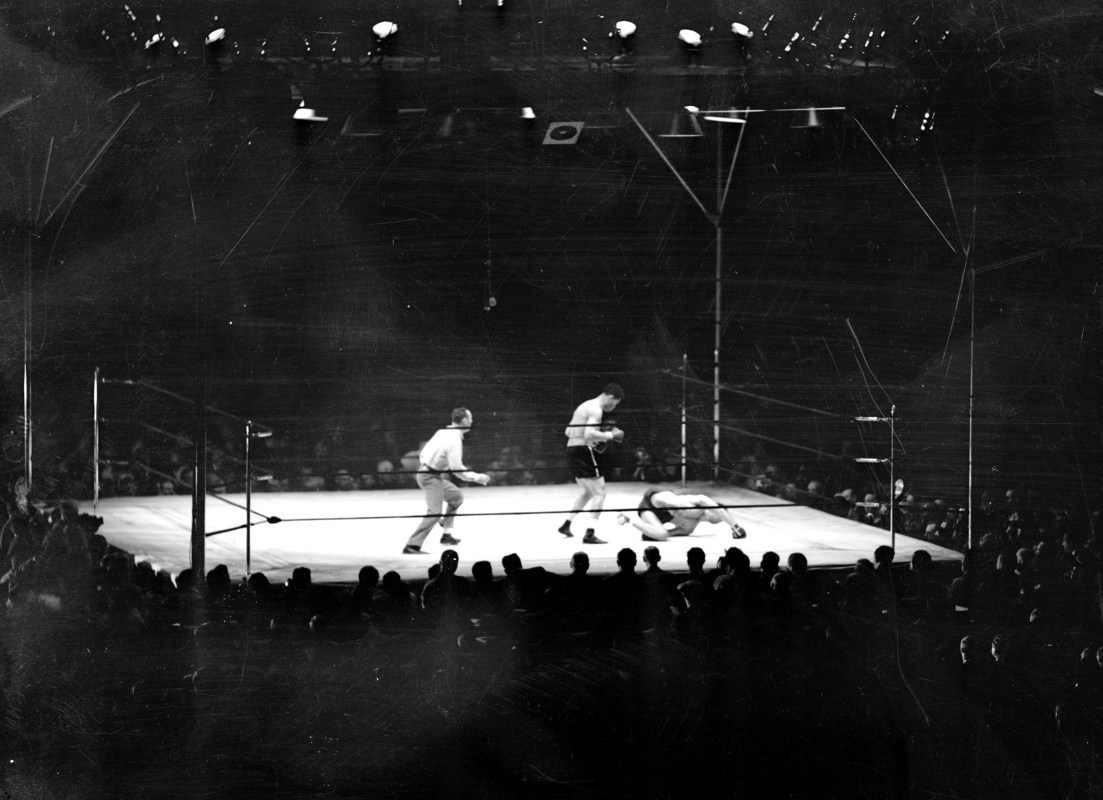

Donovan wiped Schmeling’s gloves off and made way for Louis again. The champion landed a right and a left hook to Schmeling’s body, and then, stepping away slightly to give himself room, he placed a crushing right to Schmeling’s downturned jaw, seeming to smash it, one reporter wrote, “like a baseball bat would an apple.” Schmeling crumbled to the canvas and, as Louis retreated, a white towel floated into the ring from the German’s corner, signifying surrender. Donovan tossed it away—American rules stipulated that only a referee could stop the fight—and it landed on the top rope, where it hung like a ghostly talisman. Donovan moved to start counting over Schmeling, but Schmeling’s men had had enough of the rules; they jumped into the ring to save him. Louis had won in 2:04 of the first round, just as he had promised Jimmy Cannon.

The fight was so brief that some people hadn’t made it to their seats before it was over, and late arrivals rushed into the stadium against a torrent of people filing out. But Roy Wilkins of the NAACP had no complaints. It was, he said, “the shortest, sweetest minute of the entire thirties.”

In Harlem and elsewhere, the celebrations were like nothing ever seen in black America. One writer compared it with the Fourth of July, New Year’s Eve, and Christmas Day all rolled into one. Perhaps even happier than blacks were American Jews, for whom Louis’s victory came as a temporary deliverance.

Schmeling was taken to Polyclinic Hospital in Manhattan—he was driven there in a circuitous route to avoid Harlem—where he recuperated for ten days before heading home for Germany. The Nazis did not disown him; he remained a national hero, though a diminished one. After the war, an Allied court declared him “free of Nazi taint.” He led a long life, dying at 99 in 2005, but the degree of responsibility that Germany’s greatest boxer bears for his affiliation with the Third Reich remains a subject of some debate, especially after David Margolick’s book, Beyond Glory, which came out that same year, catalogued his long record of dealings with the regime. Yet Schmeling also did something that, had the Nazis ever discovered it, would surely have cost him his remaining stature, and perhaps much more: five months after losing to Louis, in November 1938, during Kristallnacht, he sheltered two Jewish teenagers in his Berlin hotel suite, probably saving their lives—an act of heroism only revealed 50 years later, not by Schmeling but by his Jewish beneficiaries. If Schmeling’s worst was cowardly and opportunistic, his best was goodness itself.

Louis would hold the heavyweight title for almost 11 more years, reigning longer than any other champion, though his career was interrupted by the war, during which he inspired Americans with his army service. He is the true titan of American sports integration: holding sports’ richest prize a decade before Jackie Robinson integrated baseball, conducting himself in public with unfailing dignity and self-possession, he made Robinson and all that followed possible. Yet he is often forgotten today, overshadowed not only by Robinson but also by champions before and after him, Jack Johnson and Muhammad Ali, whose careers resonate more readily with contemporary political fashion. But only Joe Louis, who died in 1981, is buried in Arlington National Cemetery, where America’s greatest heroes lie.

Paul Beston is managing editor of City Journal. This article is adapted from his book The Boxing Kings: When American Heavyweights Ruled the Ring, published by Rowman & Littlefield. All rights reserved.

Whether you’re looking to get into shape, or just get out of a funk, The Charge has got you covered. Sign up for our new wellness newsletter today.